The photos and information arrived this morning from Roger Young. Thanks Roger, I'm certain this will all be of interest to the participants of this thread, and other members.

Roger wrote in his letter to me:

"Firstly I apologise that it has taken me nearly a month to organise this CD with photos, news reports and other data on the PL11 Airtruck. But, at the same time I feel it is only fair to admit that there has been a lot more work than I imagined in going through and scanning (and in some cases editing) photos and newspaper clippings. So I hop the data I have presented on the enclosed CD is some help in tjhrowing a bit of light on what I believe was a significant event in New Zealand's aviation history."Roger, no problem about the time taken, we all really appreciate it and thanks for going to the trouble.

Below is a fully detailed essay by Roger on the Airtruck's history

____________________________________________________

BRIEF (I hope) summary of the history of PL11 prototype #1By Roger Young

A writer by the name of Ray Deerness contacted me a few years ago apparently with the intention of writing a properly documented history on the two PL11 Airtruck prototypes. One of his first questions was, “When did the project actually start?”

According to my records I ceased working for Northern Air Services and started work with Bennett Aviation in August 1957. No big deal really, it was the same hangar, same workmates, same Chief Engineer [George Craig (“Snow”) Bennett, ex RNZAF and NAC – he was apparently on Guadalcanal during the war if you want to try and track his history] but just a different name on the pay slips.

Initially we dabbled with a few minor tasks on a machine designated as PL-9, but as soon as Snow heard that there were a bunch of Harvards coming up for sale he contacted Luigi Pellarini and the PL-9 design was ditched in favour of the PL11. The PL11 aircraft was designed to use the P&W R1340 Wasp engines salvaged from the Harvards, plus anything else that might be useful which, in practical terms, turned out to be mainwheels, complete wheel-brake system, rudder pedals, fuel cells, instruments and instrument panel, control column, engine controls, and parts of the canopy.

I have checked with Luigi Pellarini’s son (Frank) to see if we could nail a specific date for start of the PL11 design. Frank told me that it was almost certainly Nov-Dec 1957, as he began to work with his father in checking all the mathematical calculations on the PL11 structure very soon after completing his Matriculation exams. So we probably received the first drawings and began work in earnest on the PL11 very early in 1958.

Initially the staff consisted of Snow Bennett (Chief Engineer and shareholder in the company), Ken (“Blue”) Langtry, Wally Dowman, Jack McLeay (welder), and myself. Next additions to the staff were Bryan Busby (I understand he had been an engineer in the merchant marine) and Bob Goding (an aircraft sheet metal worker who had done his apprenticeship with TAA in Australia). Bob’s help as an instructor in sheet metal work was invaluable. I don’t know how we would have ever managed without his knowledge, instruction and skill – especially working on the cabin structure of the PL11 which involved the making of some very tricky curved shapes.

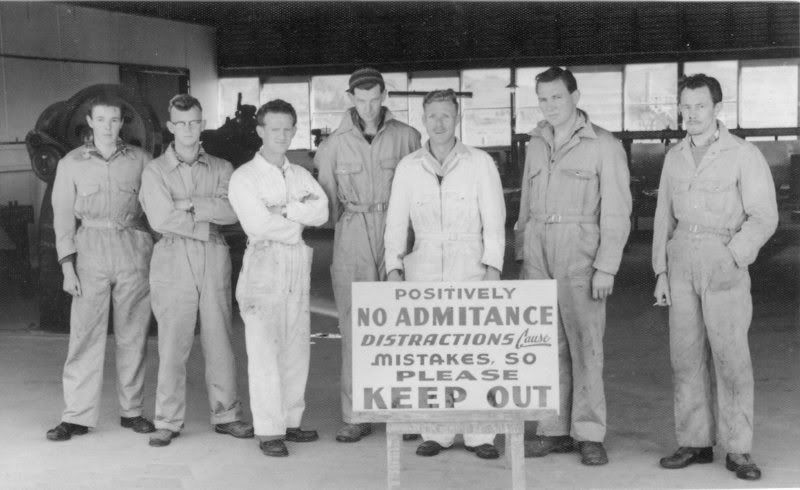

Bennett Aviation staff as at Jan 1959. From left: Roger Young, Wally Dowman, Blue Langtry, Jack McCleay, Snow Bennett, Bob Goding, Bryan Busby.

Bennett Aviation staff as at Jan 1959. From left: Roger Young, Wally Dowman, Blue Langtry, Jack McCleay, Snow Bennett, Bob Goding, Bryan Busby.[photo by Nelson Irving Studio, Te Kuiti].

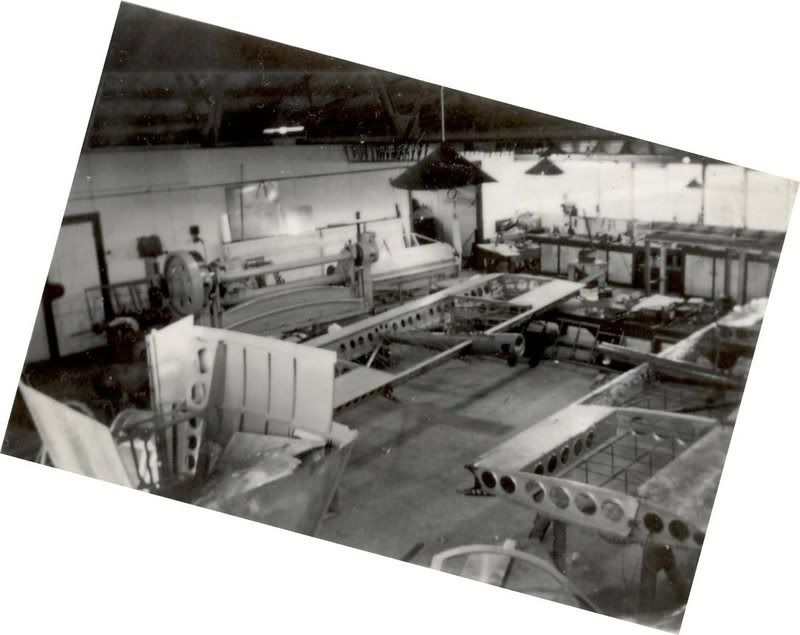

View looking into hangar, Jan 1959. The machine on the left is a power-operated guillotine (for cutting sheet metal). The man leaning over the table is Wally Dowman. The device in the background is the assembly jig we had made to assist with the formation and riveting of the leading-edge structure of the two wings (mainplanes).

View looking into hangar, Jan 1959. The machine on the left is a power-operated guillotine (for cutting sheet metal). The man leaning over the table is Wally Dowman. The device in the background is the assembly jig we had made to assist with the formation and riveting of the leading-edge structure of the two wings (mainplanes). [Nelson Irving photo]

Another shot of the inside of the workshop – probably taken mid to late 1959. The two mainplanes are almost complete – fabric covering was not added until after static testing had been completed (a task that was done on October 28-29th, 1959). The strange looking structure on the left of the picture is the fairing which was attached to the rear of the hopper to give some semblance of aerodynamics. This also provided somewhere for the loader-driver to sit on those occasions when he was flown back home at the end of a day rather than having to drive his loader vehicle all the way back to base.

Another shot of the inside of the workshop – probably taken mid to late 1959. The two mainplanes are almost complete – fabric covering was not added until after static testing had been completed (a task that was done on October 28-29th, 1959). The strange looking structure on the left of the picture is the fairing which was attached to the rear of the hopper to give some semblance of aerodynamics. This also provided somewhere for the loader-driver to sit on those occasions when he was flown back home at the end of a day rather than having to drive his loader vehicle all the way back to base. [my own photo – no copyright on this]

Within the next 12 months or so Dave Phillpotts (a licensed aircraft maintenance engineer), Geoff Young (an Aeronautical Engineer) and Kiwi Ball (a “new boy”, straight out of High School, as I had been) were added to the staff. [Kiwi had the makings of an excellent engineer, and last I heard he was working for Air Niugini. According to his mother, his licence coverage now includes “everything except Concord” – although that might have been a slight overstatement, but understandable from a mother who has every reason to be proud of her son.] Most of this team, including Snow Bennett himself, left the firm towards the end of 1960 or early 1961. Luigi Pellarini then became involved with Transavia in the development of the Australian built PL12 Airtruk, so any necessary re-working of prototype #1 (ZK-BPV) and oversight of prototype #2 (ZK-CKE) were all under the supervision of Geoff Young.

Perhaps I need to emphasise that this was no big multi-national company with almost unlimited funds – this was a very small but enthusiastic “bunch of guys” who were prepared to put in long hours of work, and work with an absolute minimum of equipment, to try and create a machine which we believed may eventually become “the ideal top-dressing aircraft” for New Zealand.

Pellarini took the concept of “a hopper with wings, engine and wheels attached” quite literally. The hopper, stub-wing, wing attachment points, engine-mount attach points, and undercarriage attachment points were all one welded assembly. A dummy (time ex) engine has been fitted just so we could be certain the engine mount brackets were in the right place and also something to hang the cowls on so we could sort of build the rest of the machine around these necessary components.

Blue Langtry working on the engine installation

Jack Worthington talking to Snow Bennett

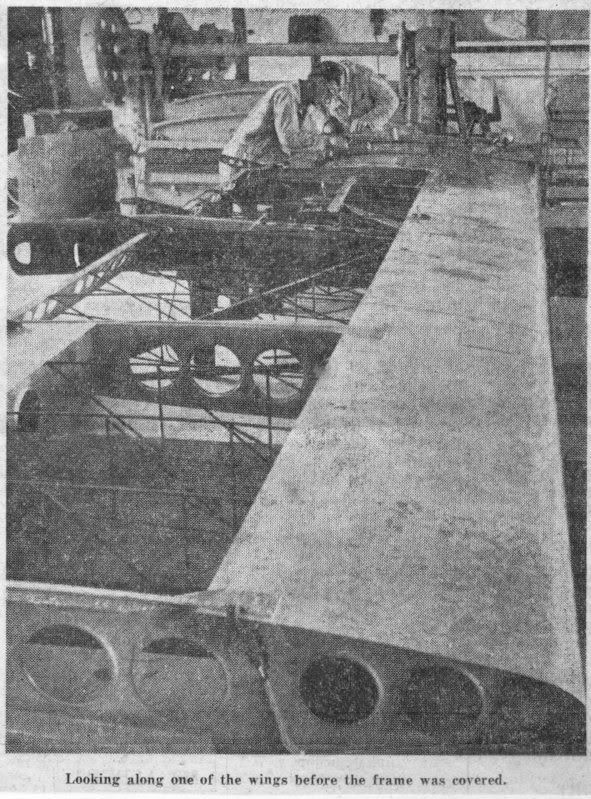

Wally Dowman working on one of the wings

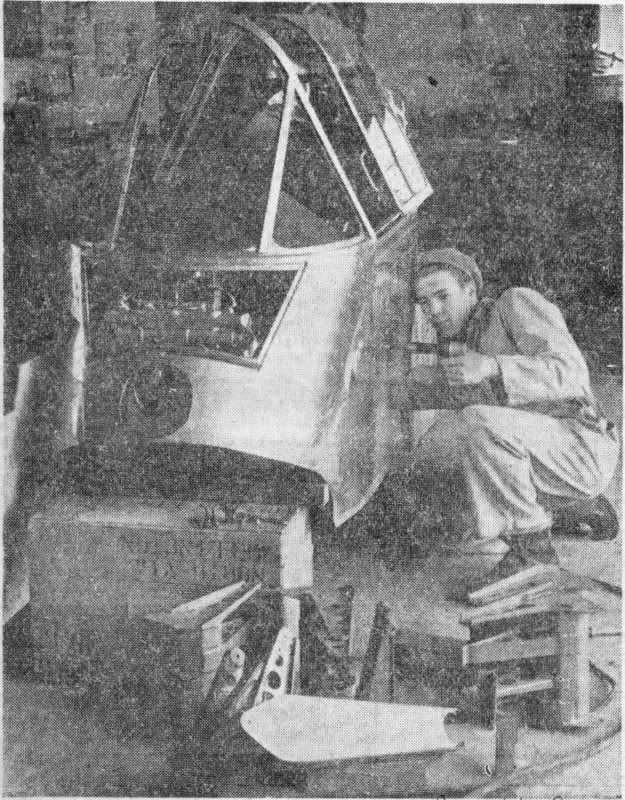

Roger Young working on the pilot’s compartment

NOTE: These two photos are both scanned from NZ Herald newspaper dated 19 Nov., 1959

Now, about those Harvards: – warbird fans please forgive us, we were only doing what we had been told (and paid) to do …. But to get these aircraft across to Lyttelton, by rail, so they could then be shipped to the North Island, we needed to cut the stub-wings off at least one side of the fuselage. Otherwise they would have been too wide on the railway flatcars to go through the tunnel between Christchurch and Lyttleton.

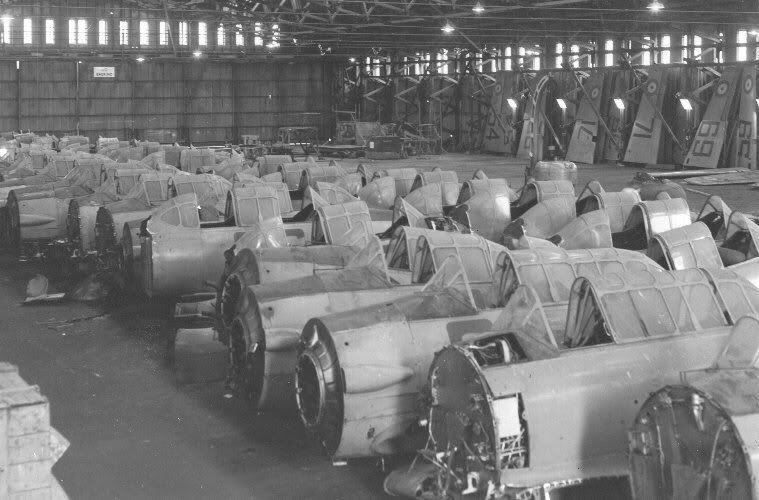

Both photos above: March 1959: No 6 hangar at Wigram “before the massacre”

Both photos above: March 1959: No 6 hangar at Wigram “before the massacre”

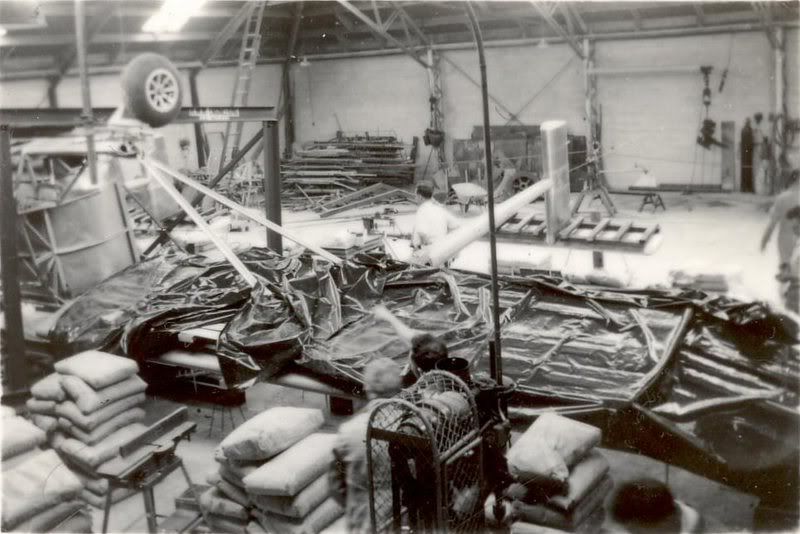

Both photos above: April 1959 – the remains, after the Bennett Team had visited

Both photos above: April 1959 – the remains, after the Bennett Team had visitedThese four photos were supplied by RNZAF photographic department in Wigram

________________________________________________

26th October 1959

These two are my own photos – no copyright problems here

First ever assembly of the almost complete aircraft – just to make sure everything fitted together as planned. Bright-eyed observers will notice that the wing-tips and fuel cells have not yet been installed.

At the same time the motor mechanic from Northern Air Services decided this was a good opportunity to check that his specially designed loader vehicle could be properly positioned to dump its load into the aircraft hopper.

After taking these photos we dismantled the whole thing and transported the parts into HWM Engineering in town (Te Kuiti) where the aircraft was assembled upside down in a huge jig and subjected to static load tests.

[Again, these are all my own photos so no copyright problems here]

27 -28th Oct. 1959Static load tests. We loaded bags of cement onto the wings and tailplanes to simulate an in-flight load of 5g. This was all closely supervised by engineers from CAA as well as by Luigi himself. Deflection of wings and tail booms were all carefully measured before, during and after applying the load and, from what I was told, were all exactly as Luigi had predicted.

The only problem we had was when one of the CAA engineers asked us to carry out a load test that would simulate the aircraft landing heavily (like falling from 6 or 8 feet) on one wheel when fully loaded at maximum take-off weight. There was no way we could really simulate a brief and instantaneous “shock load” like that, so we had to wind the load in gradually with a chain-hoist. The original stub-wing buckled under load so Luigi beefed up that part of the structure. But there were some of us who considered this part of the testing was not being fair or realistic.

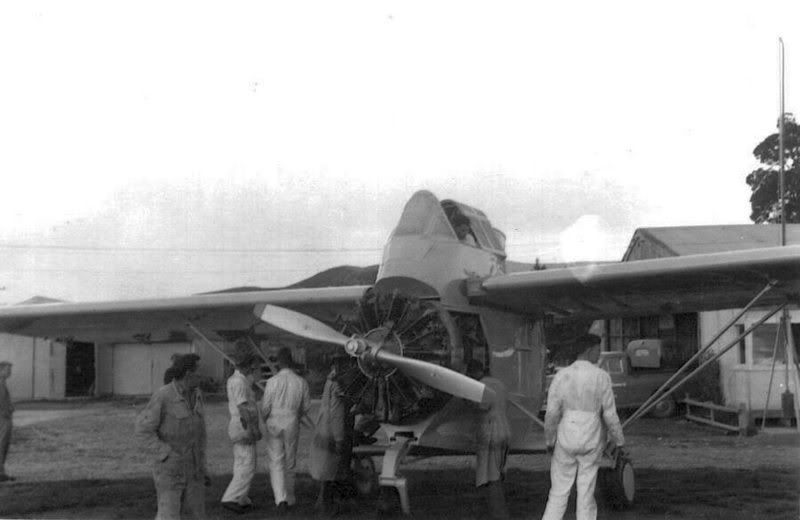

30th March, 1960 First engine run

First engine run with a newly overhauled engine. The engine overhaul had been done by Aero Engine Services Ltd at Hamilton (Rukuhia), so Snow Coleman (from AESL) and one of his staff came down to Te Kuiti for the occasion. Main problem we had was getting the beast to “stay put”. With an empty aircraft at full throttle the machine just pushed the chocks across the grass.

If you’re interested in who’s who … from left: Bryan Busby (with hands in pockets); Snow Bennett and Geoff Young looking at the starboard wing strut; two AESL engineers with their heads in the engine bay; Kiwi Ball (with his back to the camera). It is probably Ken Langtry in the cockpit.

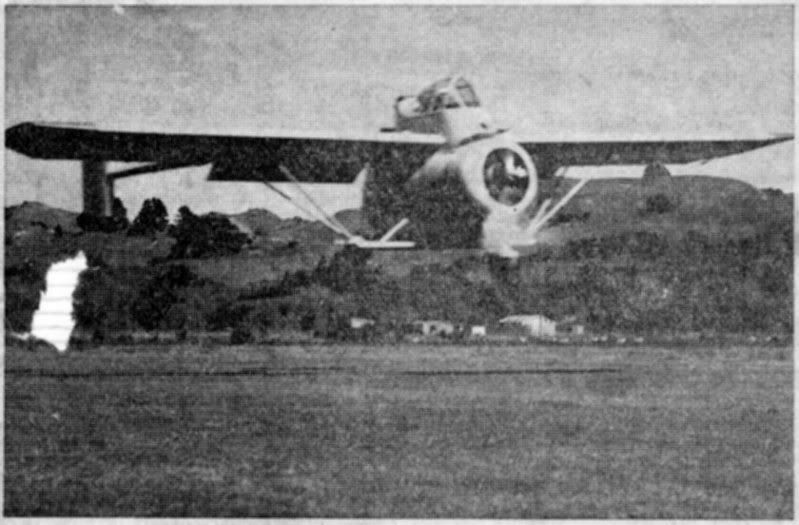

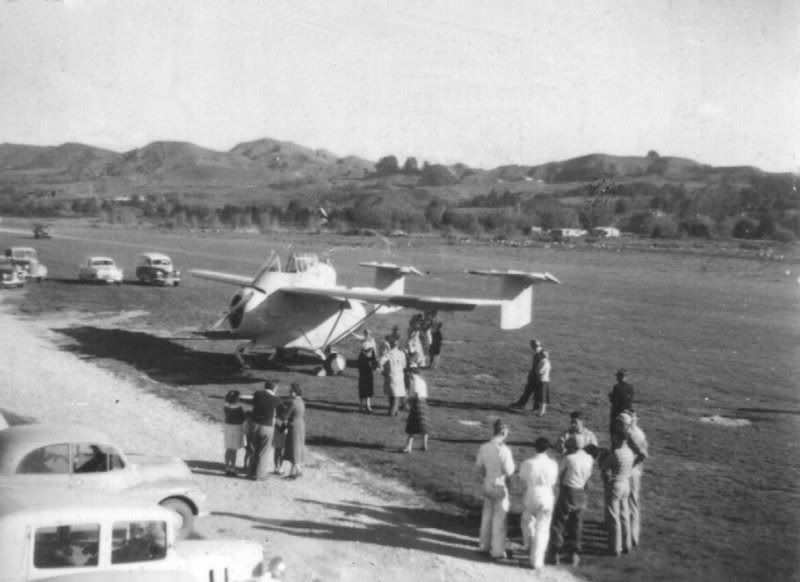

28th April 1960 The airtruck gets airborne for the first time – for a “short hop” ONLY.

NOTES regarding the photos above:

NOTES regarding the photos above: Yes, the PL11 Airtruck became airborne on its first trial “hop”. Note however, that there is no fairing between the cabin section and the engine cowling. This may have been an acceptable omission for a brief airborne hop at 35 or 40 knots but it would have been extremely unwise to have attempted any flight at airspeeds like 80 knots or more, which could have been expected with any attempt to fly a full circuit.

Apart from their concern about possible flutter with the two separate tailplanes CAA engineers were also anxious to discover whether or not there would be any evidence of nose-wheel shimmy. Pellarini had not included any shimmy-dampener in his design for the nose gear on this aircraft. He claimed that if the geometry of the tricycle gear was done correctly then a shimmy dampener would not be required, and he was most adamant that his design did conform to the correct figures. Fast taxi trials carried out on Thurs 14th April (with an engineer at the controls) had confirmed there was no nose-wheel shimmy. But the CAA engineers wanted the test pilot to also confirm there was no evidence of shimmy at take-off or landing speeds.

HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS:Tuesday 2nd August, 1960

PL11 prototype #1 ZK-BPV taxies out for its first real test flight.

Test pilot is Axel Neil Johnstone, normally known as Johnny Johnstone.

The man standing in the background (can be seen just between the two tail fins) is Jack Gardiner, the man who provided significant financial help for the entire PL11 project.

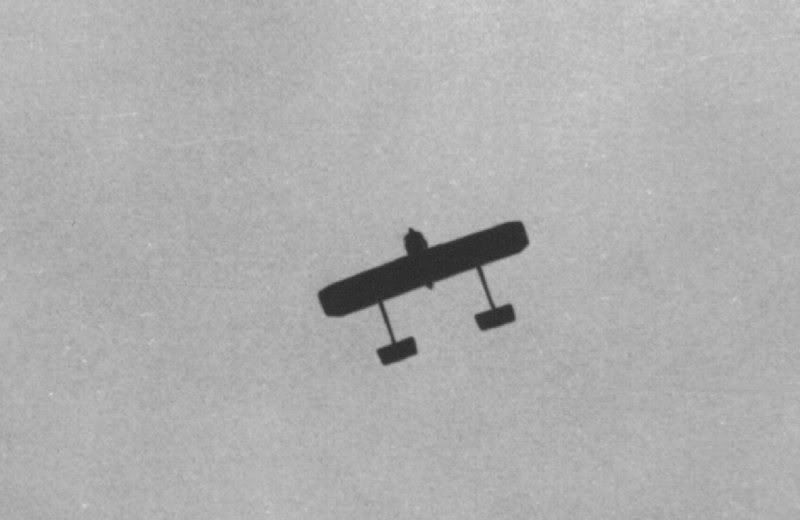

BPV gets airborne on its first real test flight. The aircraft is about three or four feet off the ground in this photo.

Except for the blurred shot at top left hand corner of this page these are all my own photos, so there are no copyright problems here

Photo taken as the aircraft flew back over the airfield shows the silhouette in plan shape.

I do not know of any words in the English language to adequately describe my feelings as I watched this “weird looking thing” that we had created with our own hands actually make a perfect take-off and climb away into the sky.

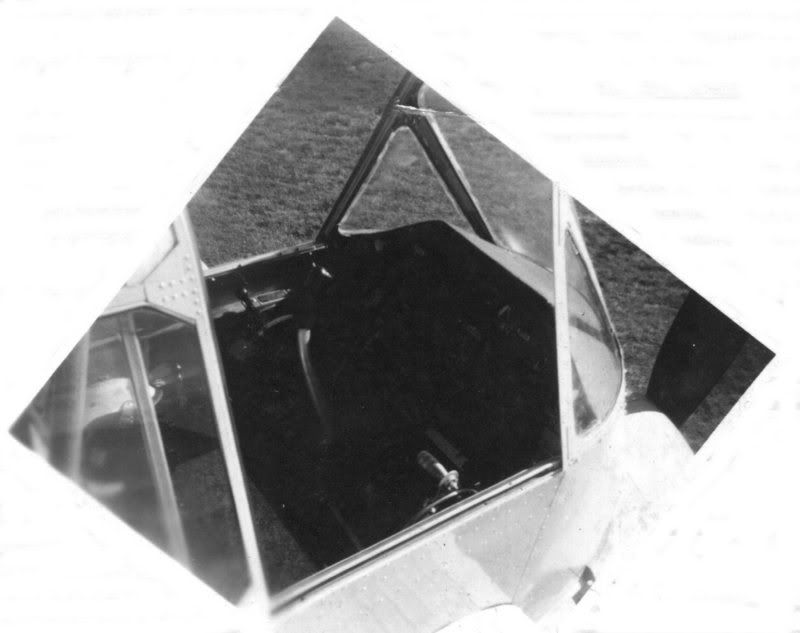

I have included a photo of the cockpit below.

Ex Harvard pilots may recognise the control column and the throttle quadrant. Unfortunately I have not discovered any way to make the instrument panel any clearer.

The handle on the right-hand side, just below the slide-track for the canopy, is the mechanism for extending the flaps. From memory I would say it required two or three full turns of the wheel to extend full flap, and, as with most STOL designs, the ailerons drooped as flaps were extended. This was one of the features that the pilots did not like – it meant having to swap hands on the control column (totally unacceptable in an ag’ aircraft, or any aircraft used in low-level operations).

One of the other features of Luigi’s design which turned out to be a big problem was the nose wheel assembly. Luigi used a rather natty arrangement of rubber blocks instead of oleo struts on all three U/C legs on this aircraft. It was meant to be simple, robust and relatively maintenance free.

However, if you check any of the early photos of PL11 prototype #1 you will see that the entire nose-gear assembly – shock-absorber and all – is forward of the pivot point used for steering. So, whenever the pilot applied any rudder deflection when the aircraft was airborne this mechanism operated like a rudder in reverse, and since it was right behind the propeller it copped the full blast of prop-wash, or slipstream (whatever you want to call it).

This meant that whenever the pilot applied even a small amount of rudder he would suddenly find that the system wanted to slam over to full deflection. So, one of Geoff Young’s first jobs, when he took over from Luigi, was to design a completely different mechanism for the nose gear. I understand his first attempt used an oleo strut from a Harvard tailwheel. They then tried one of the oleos from the main gear. If you look carefully at photographs of ZK-BPV you should notice how the design changed, or evolved, until the final arrangement as used on ZK-CKE.

I left Bennett Aviation three weeks after the first test flight of ZK-BPV so, apart from what I have since learned when talking to Geoff Young I am not able to really comment with any authority on changes that were subsequently made to the PL11 design.

PS: I consider the following comments from the Test Pilot’s report to be worth recording [But what I have is an ancient photo-copy which is sometime difficult to read]

CONCLUSIONS:

2 Reference has been made in previous reports to load discharge interferences, which cause large tail-load changes in aircraft of conventional layout. Under critical conditions in certain aircraft these effects can be serious, and their importance should be far better understood than it is.

In [this situation] the effects have been nullified by the simple expedient of placing the horizontal tail surfaces outside their reach. [In other words, another very good reason to have the two separate tailplanes – at the time this was a unique characteristic of the PL11.]

3 In aircraft which have a filler opening flush with the upper surface of the mainplane, back-flow of air through open hopper doors will cause a large loss of lift. Under critical circumstances such a loss of lift is dangerous.

There is no such effect on this aircraft, which has the filler opening situated well above the wing surface.

4 It has been stated in previous reports that the basic flying qualities of the aircraft are excellent. The average pilot will have no trouble in converting to the type, and will find it easy and safe to operate from airstrips of adequate length.

5 Cross-wind handling characteristics are good.

6 Pilot’s field of view is outstanding.

I cannot escape the conclusion that an element of opposition exists in certain quarters on the score of the aircraft’s appearance. After 24 years of flying I have yet to be convinced that there is more than a fortuitous relationship between aerodynamics and aesthetics; such an attitude is the refuge of ignorance. This aircraft represents a particular solution for a set of highly specialized problems ….

[unfortunately at this point the photo copy reached the bottom of the page and is unreadable from here on. But it seems safe to conclude that test pilot Johnny Johnstone was basically very happy with the performance of the aircraft and recognised that the unusual aspects of the design (as regards physical appearance) were all there for good reasons and actually enhanced the safety and overall performance of the machine. ]

Perhaps one other person who should get a mention was Mr C W (“Snow”) Penman. He ran an automotive electrical business in Te Kuiti, but had also worked with the RNZAF as an instrument and electrical technician. It was his responsibility to install and check all the engine instrument systems and all the electrical wiring (not that there was much of that, and we used wiring salvaged from those good old Harvard aircraft).

Its interesting, in retrospect, that three of the engineers who worked on the PL11 project had the nickname “Snow”. I hadn’t actually registered that bit of trivia until I tried to put some of the history of this endeavour into writing.

And, one other bit of historical trivia – Snow Bennett and test-pilot Johnny Johnstone both eventually went to Australia and worked with Luigi Pellarini in the development and design of the Transavia PL12.

Roger Young

12 November, 2007