|

|

Post by Dave Homewood on Jun 28, 2014 12:45:13 GMT 12

|

|

|

|

Post by kiwithrottlejockey on Jun 28, 2014 21:28:17 GMT 12

from The Guardian....Archive, June 1914: The assassination of Archduke Franz FerdinandFirst world war: How the Manchester Guardian reported the

murder of the Austro-Hungarian Archduke by Gavrilo Princip.By RICHARD NELSSON | 5:38PM BST - Thursday, 26 June 2014 An artist's rendition shows the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of An artist's rendition shows the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of

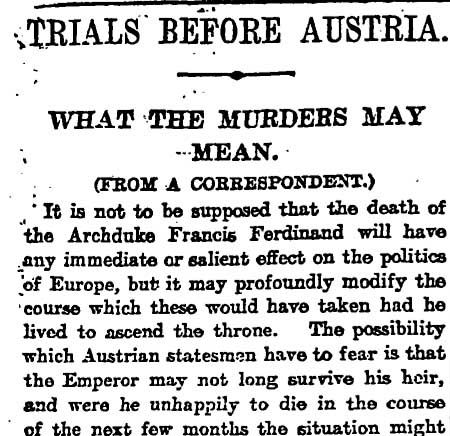

Austria-Hungary and his wife, 28th June, 1914. — Photo: Associated Press.THE assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife on 28th June 1914 sparked a chain of events that led to the outbreak of the First World War. The Manchester Guardian, 30th June 1914. Click on image to read.The news of the murders was heard with horror throughout the world but few could have foreseen what was about to unfold. A Manchester Guardian analysis piece about the events in Sarajevo began by stating that "It is not to be supposed that the death of the Archduke Francis Ferdinand will have any immediate or salient effect on the politics of Europe." (see above) The Manchester Guardian, 30th June 1914. Click on image to read.The news of the murders was heard with horror throughout the world but few could have foreseen what was about to unfold. A Manchester Guardian analysis piece about the events in Sarajevo began by stating that "It is not to be supposed that the death of the Archduke Francis Ferdinand will have any immediate or salient effect on the politics of Europe." (see above)

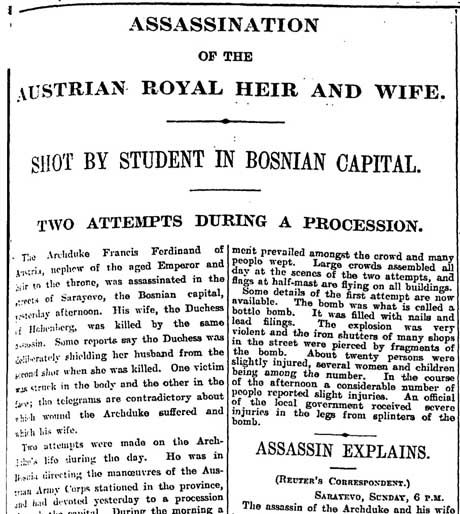

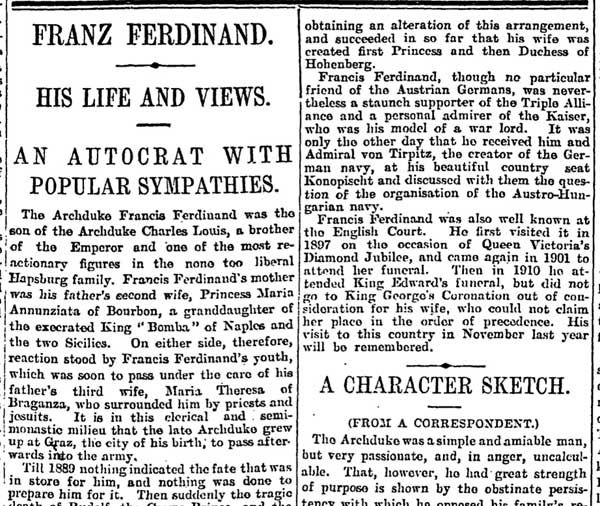

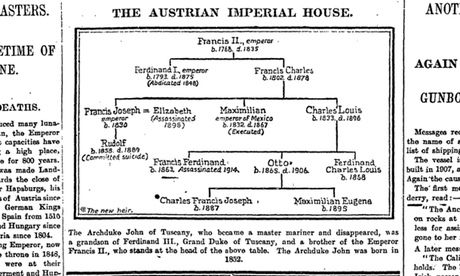

Nevertheless, the killing of a European monarch generated coverage for several days. There were news reports on all angles of the story, as well as an in-depth editorial on 29th June. The Manchester Guardian, 29th June 1914. Click on image to read. The paper also informed its readers that "The Hapsburgs (sic) have produced many lunatics and one great statesman", as well as publishing a profile and sketch of the "autocrat with popular sympathies". The Manchester Guardian, 29th June 1914. Click on image to read. The paper also informed its readers that "The Hapsburgs (sic) have produced many lunatics and one great statesman", as well as publishing a profile and sketch of the "autocrat with popular sympathies". The Manchester Guardian, 29th June 1914. Click on image to read.Finally, a helpful graphic was produced to illustrate the Habsburg family tree. The Manchester Guardian, 29th June 1914. Click on image to read.Finally, a helpful graphic was produced to illustrate the Habsburg family tree. The Manchester Guardian, 29th June 1914.• When the Lamps Went Out, edited by Nigel Fountain, is a collection of the Guardian's best WW1 reporting. Available for £12.99 (RRP £17.99) at the Guardian Bookshop.www.theguardian.com/theguardian/from-the-archive-blog/2014/jun/26/first-world-war-franz-ferdinand-assassination-1914 The Manchester Guardian, 29th June 1914.• When the Lamps Went Out, edited by Nigel Fountain, is a collection of the Guardian's best WW1 reporting. Available for £12.99 (RRP £17.99) at the Guardian Bookshop.www.theguardian.com/theguardian/from-the-archive-blog/2014/jun/26/first-world-war-franz-ferdinand-assassination-1914

|

|

|

|

Post by kiwithrottlejockey on Jun 28, 2014 21:54:22 GMT 12

from The Guardian....How the Guardian played down the assassination that sparked World War]Murder of Archduke would have no ‘salient effect’ on Europe,

declared Manchester Guardian, just 37 days before war erupted.By RICHARD NORTON-TAYLOR | 1:40PM BST - Friday, 27 June 2014 Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his pregnant wife Sophie moments Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his pregnant wife Sophie moments

before they were assassinated in Sarajevo on 28th June 1914.

— Photo: Popperfoto."IT IS not to be supposed," wrote a correspondent for the Manchester Guardian analysing the significance of the assassination 100 years ago on Saturday, "that the death of the Archduke Francis Ferdinand will have any immediate or salient effect on the politics of Europe."

Thirty-seven days later, Britain declared war on Germany and Europe was plunged into a worldwide conflict in which more than 16 million people died in four years.

But it is hardly surprising that the Guardian did not predict the unimaginable horror to come. The newspaper's editorial of 29th June 1914, the day after the assassination, dwelt on the Archduke's personality and on the narrow implications it might have for the internal politics of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

"What its motives may have been we do not know, nor do they greatly matter," it advised its readers. "It is a difficult and at present an ungracious task to speculate on what influence the crime of yesterday may have on Austrian politics."

The Archduke, the editorial noted, was "a great gardener", adding that "in England, under other conditions of life, he would have been an ideal country squire". Franz Ferdinand was described as "a simple and amiable man, but very passionate and, in anger, uncalculable".

The Manchester Guardian, then edited by the legendary C.P. Scott, was far from alone in playing down the significance of the death of the Archduke, shot by the young radical Bosnian Serb, Gavrilo Princip, in Sarajevo. The Sleepwalkers, historian Christopher Clark's seminal work on how Europe went to war in 1914, reflects the mixture of complacency and rhetoric Europe indulged in. Gavrilo Princip, the radical Bosnian-Serb Gavrilo Princip, the radical Bosnian-Serb

nationalist who assassinated the Archduke.

— Photo: Charlie Riedel/Associated Press.But the Guardian did devote the bulk of its main news page, illustrated by a small map and family tree of the Austrian royal house, to the shooting.

Reports from correspondents of the news agency Reuters in Sarajevo and Vienna detailed the circumstances surrounding the assassination and described an earlier attempt shortly before Princip fired the shots that killed the Archduke and his wife.

The assassins were "almost lynched by the infuriated crowds … many people wept", Reuters reported.

The next day, 30th June 1914, a Guardian headline read "World's Sympathy with Aged Emperor". The paper noted that the Archduke and his wife had recently visited London and, his uncle, emperor Franz Joseph, held the title of a British field marshal.

The article added: "Comments on the crime, all expressing friendly feelings for the Emperor, are made by all the European papers, most of them, as is natural while the shock is still fresh, attaching an over-importance to the political consequences."

Though the newspaper's first analysis — headlined What the Murders May Mean — played down the "immediate or salient" effect on European politics, it did warn of the dangers of increased hostility between Austria and Serbia. It also warned of "the more serious danger of a Russian attack" on Austria in defence of its Slavic ally.

The Guardian opposed British intervention right up to the declaration of war. "We care as little for Belgrade as Belgrade for Manchester," it told its readers on 30th July. On 1st August, C.P. Scott argued that intervention would "violate dozens of promises made to our own people, promises to seek peace, to protect the poor, to husband the resources of the country, to promote peaceful progress".

Four days later, after Britain declared war on Germany, the Guardian said: "All controversy therefore is now at an end. Our front is united."

But, the newspaper added: "A little more knowledge, a little more time on this side, more patience, and a sounder political principle on the other side would have saved us from the greatest calamity that anyone living has known.

"It will be a war in which we risk almost everything of which we are proud, and in which we stand to gain nothing."www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/27/guardian-1914-analysis-archduke-franz-ferdinand-shooting

|

|

|

|

Post by Mustang51 on Jun 30, 2014 8:06:23 GMT 12

And the fall-out from the reparations demanded from Germany post WW.I started the growth of all of the seeds of WW.II

|

|

|

|

Post by kiwithrottlejockey on Jun 30, 2014 14:49:03 GMT 12

And the fall-out from the reparations demanded from Germany post WW.I started the growth of all of the seeds of WW.II I was reading the following news story from the Chicago Tribune yesterday and it mentions WWII being one of the aftermaths. Click on the two images to read the Chicago Tribune's news stories from 100 years ago about the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand (both will download as PDF documents).

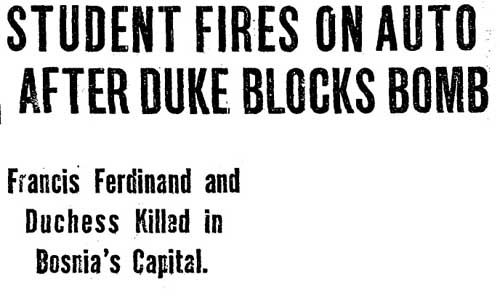

from the Chicago Tribune....100 years later, remembering the crucible called World War IThe “ar to end all wars” didn't, but it did change warfare and the world forever.By HENRY CHU - reporting from London | 10:45AM CDT - Saturday, June 28, 2014 See: Front page blasting news of the Archduke's death (click on image).THE SHOT that changed the world rang out on a sunny summer's morning in Southeastern Europe. No one knew then that the assassin's bullet would spell the death not just of an Austrian aristocrat but the entire global order, with four empires and millions of lives lost in a conflict on a scale never before seen. See: Front page blasting news of the Archduke's death (click on image).THE SHOT that changed the world rang out on a sunny summer's morning in Southeastern Europe. No one knew then that the assassin's bullet would spell the death not just of an Austrian aristocrat but the entire global order, with four empires and millions of lives lost in a conflict on a scale never before seen.

Exactly 100 years ago on Saturday, Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian empire, and his wife, Sophie, were shot at close range by a young Serbian nationalist on the streets of Sarajevo.

The assassination set off a chain reaction that, barely a month later, culminated in a continent at war.

What many thought would be a brief, even heroic, conflict metastasized into a four-year nightmare that engulfed dozens more nations, including the United States, redrew the map of Europe and introduced the world to new horrors such as chemical weapons and shell shock. A second, even deadlier global catastrophe, which had its seeds in the first, struck within a generation.

For many modern-day Europeans, the conflict is emblematic of the madness of war.

In such a cataclysm there are no winners, many say, and it's fruitless to seek logic, meaning or justification in soldiers asphyxiating in gas attacks, or waves of men charging over the tops of trenches only to be mowed down by machine-gun fire within seconds.

This week, European leaders gathered to remember those sacrifices at a solemn ceremony in Ypres, Belgium, where countless soldiers fell on the muddy fields of Flanders.

"This commemoration is not about the end of the war or any battle or victory," said Herman Van Rompuy, a former Belgian prime minister. "It is about how it could start, about the mindless march to the abyss, about the sleepwalking — above all, about the millions who were killed on all sides, on all fronts."

Van Rompuy is now president of the council of the 28-nation European Union, an expression of regional comity and solidarity that could scarcely have been imagined 100 years ago.

The union is far from perfect: Leaders bickered publicly this week over who ought to be handed one of the EU's plum jobs, and recent elections to the European Parliament produced a crop of winners from parties avowedly hostile to further integration. But in 2012, the EU was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of how far Europe has put its blood-soaked past behind it.

In another sign of healing divisions, French President Francois Hollande will dedicate a memorial in November inscribed with the names of all 600,000 troops who perished in northern France during World War I, regardless of which side they fought on.

That seems to mirror a new tendency to gloss over the question of who was to blame for the war — many label Germany the chief aggressor — and focus instead on what happened, said Annika Mombauer, a historian at Britain's Open University. Such an approach sits uneasily with her.

"Given the countless victims the war claimed, the unimaginable horrors that were inflicted all over the world, it is fair and justified to pose the question of who was ultimately responsible for this," she said. "Of course, we have not managed to agree on an answer in a hundred years, and doubtless we never will."

"The crisis of 1914 shows us that it is dangerous to be too complacent, to assume that bluff will work and that the other side will not ultimately be prepared to go to war," Mombauer said. "The decision-makers of Austria-Hungary and Germany deliberately took the risk that the crisis they provoked might escalate into a full-scale war. The other governments were prepared to call their bluff." Read: The 1914 Chicago Daily Tribune article on the assassination (click on image).THE GREAT WAR also underscored the rise of the United States and the dawn of an American century. The principle of self-determination of nations took root, which continues to be tested. Three months from now, Scotland will vote on independence from Britain; Catalonia seeks a similar referendum on secession from Spain. Read: The 1914 Chicago Daily Tribune article on the assassination (click on image).THE GREAT WAR also underscored the rise of the United States and the dawn of an American century. The principle of self-determination of nations took root, which continues to be tested. Three months from now, Scotland will vote on independence from Britain; Catalonia seeks a similar referendum on secession from Spain.

The idea of bringing nations together in an international talking-shop aimed at keeping the peace also crystallized in the ashes of World War I.

In some ways, the Great War was a family affair: King George V of Britain, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany and Czar Nicholas II of Russia were cousins.

The war swept away most of those dynasties. The Russian Revolution ushered in the world's first communist state; a defeated Germany witnessed the birth of the Weimar Republic. The Ottoman Empire was broken into pieces, and the map of the Middle East was redrawn as well.

Islamic militants this month tore down border posts along the frontier between Iraq and Syria, a line drawn after the Turkish empire was dismembered. The central question for Iraqis is whether their country, defined by those borders, can survive.

Across Europe, not just the political but the old social older crumbled as a result of World War I.

"The Great War … was a rupture," Van Rompuy said. "This is the end of yesterday's world, the end of empires, aristocracies and also an innocent belief in progress."

Nenad Prokic, a Serbian playwright and former lawmaker, struggles to make sense of the conflict a century after his compatriot, 19-year-old Gavrilo Princip, angry about Austria's annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, gunned down Franz Ferdinand. A month after the assassination, Austria-Hungary retaliated, its ally Germany moved on France, Russia and Britain mobilized their forces, and within a week, all had formally declared war.

The repercussions were enormous on Prokic's country, which lost a quarter of its people, including more than half its male population.

"We could not recover from that," he said.

The nation of Yugoslavia, and a fragile hope, emerged from the rubble. But that fell apart violently, too, in the Balkan wars of the 1990s, which gave the world the brutal euphemism of "ethnic cleansing". Serbia, an international pariah for years afterward, is hoping to rehabilitate its image and gain a foothold in the EU.

"Now we are trying for a quarter of a century to organize a new state for us — very unsuccessfully, I must say," said Prokic, who lives in Belgrade.

In his new play, "Finger, Trigger, Bullet, Gun", Prokic explores the buildup to World War I and the "human stupidity" that tries to turn mass carnage into virtue. The drama premieres Saturday at the London International Festival of Theatre, which is devoting the entire weekend to works dealing with the war's enduring aftermath.

Onstage will be more than 19,000 dominoes, for the number of British soldiers killed on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. At the close of the play — which ends in the present, with the characters discussing Europe and the crisis over Russia's seizure of Crimea this year — the dominoes will be toppled.

Naturally, the first domino represents Franz Ferdinand, whose death June 28th, 1914, touched off the war that was supposed to end all wars.

"One hundred years ago, the butchery began, and so many lives disappeared," Prokic said. "We must at least try for a moment to avoid such a big catastrophe in the future."Related news stories:

• Skirmishes flare over WWI centennial plans

• In Sarajevo, WWI's wounds still fresh

• Bosnian Serbs honor assassin with statuewww.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/chi-100-years-world-war-i-20140628,0,7599956,full.story |

|

|

|

Post by Calum on Jul 1, 2014 14:58:58 GMT 12

The ultimate Irony was Ferdinand was the only Austro-Hungarian Leader who didn't want war with the Serbs/Russia, and probably could have prevented it.

And don't forget, Germany could have prevented war by not supporting Austria, but instead they chose to given them a "blank cheque" to invade Serbia. Something Austria had been wanting to do for years.

|

|

|

|

Post by Dave Homewood on Jul 2, 2014 16:18:12 GMT 12

I highly recommend the excellent series Month Of Madness, currently available on BBC Radio's website. it explains exactly what occurred, from all angles, really well. www.bbc.co.uk/podcasts/series/ww1 |

|

|

|

Post by nuuumannn on Jul 2, 2014 18:07:21 GMT 12

Yep, so true. The stupidity of the Great War is that no one really wanted it and it really wasn't necessary and, contrary to popular and historical belief, it was not inevitable. Nor was the Arch Duke's assasination a real step toward war. In recent times this view has been challenged. It was made the first step in a chain of events through circumstance, but not out of necessity.

The Arch Duke wasn't a popular man, within the European Aristocracy and among the Austro-Hungarian public. When the A-H government spoke of war with Serbia, no one thought going to war in Serbia's defence was worth it and even when A-H went to war with Serbia, its armies were given such a harsh time that they really didn't have a taste for it. Russia's reaction to the whole thing was what any ally would do, send troops to the border as a show of strength and solidarity, but Nicholas was not keen on war with A-H because of the Germans. And this is where the push for European war came from. German generals offered the 'blank cheque' and stated that war was inevitable - even asking the British, who sensibly wanted no part in it all, for their permission to go through Belgium and attack France. And why France? Because of its support for Russia's stance.

Craziness. Britain only jumped in out of a miss-guided sense of morality over Belgium being invaded, since the Belgians said no to German requests to transit through the country to get to France, which forced the Germans to invade. Even then, Britain was, to a degree, scorned by France, who wanted it to jump in and help, against what Asquith privately thought was better judgement, so then, based on a moral soap box, Britain and the Empire needlessly went to war, because the Germans wanted to go through Belgium to get to France and Belgium wouldn't let them!

|

|

|

|

Post by errolmartyn on Jul 2, 2014 18:46:07 GMT 12

"which forced the Germans to invade."

Er, not they weren't. No one held a gun to their head and demanded that they invade. At the end of the day they chose to invade.

Errol

|

|

|

|

Post by nuuumannn on Jul 2, 2014 19:14:04 GMT 12

That's the point I'm trying to make, Errol - no one 'forced' the Germans into any situation that led them to war. They started it and pushed for it and the excuse of the Archduke's assasination has been used as the pretext for war ever since. Perhaps I should have placed the word 'forced' into quotations to make that clearer.

|

|

|

|

Post by alanw on Jul 3, 2014 10:09:59 GMT 12

Of interest, I read just recently ( I can't remember where) that after the armistice, the likes of Gt Britain, Russia, and even the United States were not keen on making Germany pay reparations. The spanner in the works was France who wanted Germany to pay. Eventually the others followed suit (France obviously had a smooth tongue)and thus begat the seeds of the future WWII.

Knowing what France wanted, makes more sense now why Hitler wanted France to sign it's agreement to surrender at Versaillies in the same railway carriage.

Regards

Alan

|

|

|

|

Post by Calum on Jul 3, 2014 14:37:31 GMT 12

It's also notable that WW1 ended the monarchies of 2 of the main protagonists, Russia and A-H

You can also argue that first world war was the cause of much to the conflicts of the 20th century

Think (not in any particular order)

No WWI

Perhaps No Communist Revolution in Russia

Likely No Nazi Germany

Likely No WW2

Likely No Cold war

No Korea/ Vietnam

|

|

|

|

Post by Dave Homewood on Jul 3, 2014 14:41:41 GMT 12

Mankind would still have found a way to make war Calum. It's a natural instinct of most politicians... and big money industrialists

|

|

|

|

Post by Dave Homewood on Jul 3, 2014 14:43:20 GMT 12

It's quite amazing listening to the BBC programmes how stupid the Arch Duke was in ignoring his advisers, and others, by ploughing on with his tour and visit, even after the first attempt on his life failed that same day! What a plonker. He won't do that again.

|

|

|

|

Post by nuuumannn on Jul 4, 2014 13:06:28 GMT 12

Actually, all those countries wanted reparations. The top of Britain's list was the High Seas Fleet. What they weren't keen on was accepting Wilson's Fourteen Points, which Germany eventually accepted.

Sadly, you're right Dave. Calum, the Russian Revolution was going to happen regardless and the thing that the communists did was have quite an impact on the working class around Europe after the revolution. In France, Germany and Britain, communist parties sprang up as workers sought equality. Throughout the Great War, in Britain there were strikes-a-plenty as the work force wanted more for their extra efforts. Regarding Germany, after Jutland, communism spread through the lower ranks of the navy as the ships of the High Seas Fleet swung about their anchors at Wilhelmshaven. Riots frequently broke out between communist sympathisers and the officers.

When the order to surrender was given and the ships set sail for Britain, communits were delighted to see, on entry to the Firth of Forth, some of the British ships of the Grand Fleet were flying red banners and it is reported that on more than one ship, the German sailors gave a cheer when they saw these - they were part of the exercises that the British arranged; Operation ZZ - as the other ships flew blue banners. There was change sweeping through Europe and looking at domestic issues that were affecting each country out with the war, much was happening. In Britain alone, the thorny issue of Irish independence was capturing headlines, as was universal sufferage, a striking work force, so they had their hands full.

Sophie Chotek. She was never a full Imperial Majesty and never held the ceremonial rank that was bestowed on the wife of an Archduke. In public the two were not to be seen sitting together and she did not stand at his side in an official capacity because of this. One loophole that the couple found was that as commander of the armed forces, Ferdinand could have his wife next to him in a military capacity. He has been described as a difficult man and she a difficult woman, but their relationship was far from loveless. He loved his wife and she her husband and its been suggested that his love for her and having her at his side, prompted the tour of Sarajevo. Love is in the air...

|

|

|

|

Post by Dave Homewood on Jul 4, 2014 13:29:43 GMT 12

But them wanting to go to Sarajevo is one thing, insisting on carrying on with public engagements even after a bomb was thrown at their car and nearly killed them despite warnings from their advisers is pretty stupid indeed. I'm sure other public figures learned from this mistake.

|

|

|

|

Post by nuuumannn on Jul 5, 2014 14:27:50 GMT 12

Actually, they made a decision to leave the streets after the bomb was thrown, but before they could, their driver happened to turn down the road where Princip was standing, purely by chance. On realising that he had taken a wrong turn, the driver stopped the car and was about to reverse and it was then that Princip saw the vehicle and his date with destiny. He wasn't expecting the Archduke's vehicle there at that moment at all; he just happened to be at the right place at the right time - for desperate want of a better expression...

|

|

|

|

Post by Dave Homewood on Jul 5, 2014 21:58:24 GMT 12

That's not the full story there Grant. From what the various BBC programmes in past weeks have said, they did not immediately "leave the streets". The Archduke insisted on carrying on with his planned programme because he was sure the bomber was a madman acting alone, and he'd been captured. They did carry on, to the city hall, where much to the fear of the Sarajevo Major and the Archduke's aids, he gave a public speech, as planned. It was only after this that the aids finally convinced him it was a bad idea to be in public, and that they should get out of town. They planned an alternate route to that which had been publicised, but no-one told the driver in the lead car. He carried on unknowingly on the old route and it was after he was alerted that the route had changed he came to a halt to try to get the facts straight or to turn round - and he just happened to halt right next to where the assassin was standing and waiting. So I guess it was "meant to be". Had someone briefed the drivers properly he'd never have been shot.

|

|

|

|

Post by nuuumannn on Jul 6, 2014 15:01:46 GMT 12

No, no one explained to the driver the route they were to take to the hospital, where the party were going to meet the victims of the grenade explosion. By then, continuing the tour had been decided against. The problem was that the original route was published in advance and little security was put in place to ensure that their lives were not in danger. There were only 60 police officers on duty at the time. After the speech at the hall, where the Archduke was visibly shaken during which he interrupted a speech by the mayor, a suggestion was made that they stay at the town hall and await the arrival of troops, but this suggestion was vetoed by Governor General Oskar Potiorek, who had had the route the Archduke's cavalcade published previously, because the troops would not have the right uniform for such an occasion! Gasp! (There's been some suggestion that he was also complicit to the assassination, but nothing was ever proven) Nevertheless, the decision was made to go and visit victims of the grenade explosion in hospital and that's when the itinerary change was decided upon and the tour was discontinued.

After the kerfuffle and the failed attempts on the route of the Appel Way, Princip thought the best place to catch him would be on the tour route off the Appel Way, and not knowing that the tour had been canned by this time, he went to Franz Joseph street further along the tour route, also not knowing that the Archduke's car would actually be there at the time that it was, so it was with some surprise to Princip that it appeared when it did. Potiorek had hoped to travel along the Appel Way straight to the hospital to avoid the crowds in the centre of the town, but instead the driver turned down Franz Joseph Street, which happened to be the original route the cavalcade was to take at any rate instead of continuing along Appel Way as Potiorek had hoped. Potiorek called out for him to stop the car and return to the Appel Way and thus he did so and had begun to reverse. This is where Princip happened to be waiting, but not actually expecting to see the car when he did and took his chance.

You are right in one way that it was 'meant to be'. It was a cruel twist of fate and the holes in the cheese all lined up for that big event.

|

|