Post by Dave Homewood on May 1, 2016 18:00:06 GMT 12

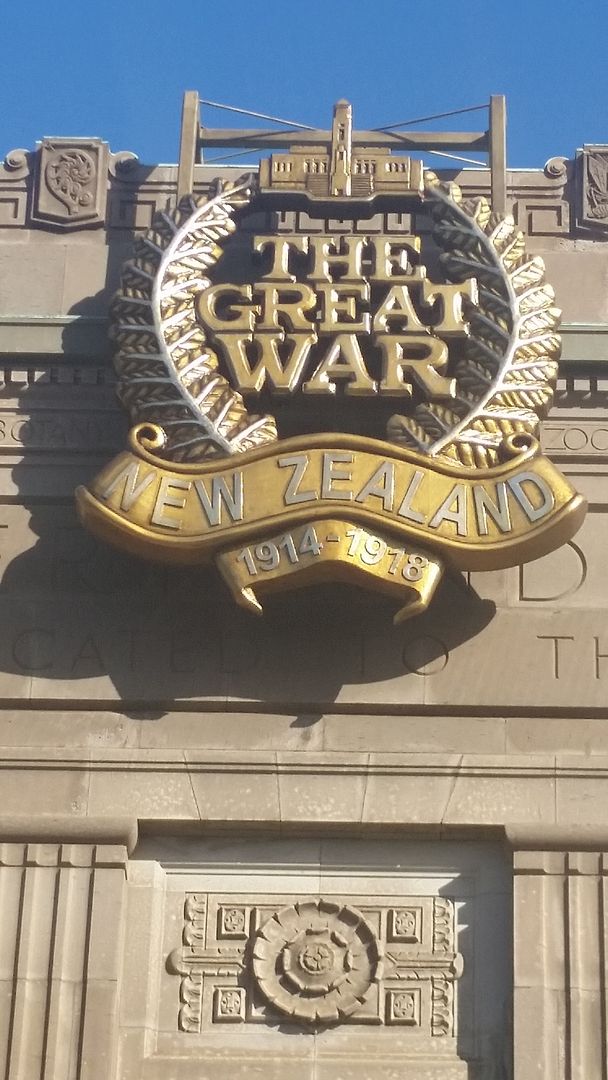

This amazing collection of first hand memories of the landing at ANZAC Cove on the 25th of April 1915 comes from The Star newspaper, dated 25 April 1916.

A YEAR AGO

During the past few days representatives of the "Star" have interviewed several officers and men who took part in the famous landing a year ago today. The accounts obtained afford interesting glimpses of stirring events and, in many ways, bring home the difficulties of that magnificent military venture.

CAPTAIN WALLINGFORD, M.C.

The nation knows of Captain Wallingford, one of the best shots the British Army has ever turned out, who was in charge of New Zealand's machine guns at the landing and after an arduous and brilliant campaign was invalided and received the Military Cross. Captain Wallingford, who joined New Zealand's Main Body from the position of musketry instructor in tho Auckland military district, was in Christchurch a few days ago and a "Star" reporter was lucky enough to run across him just before he left again for the north. In a very hurried interview Captain Wallingford gave his impressions of a year ago to-day.

"Very early on the morning of Sunday. April 25, 1915, it having been decided to land on one of the beaches, I was called to a conference with General Godley and I was there four hours. It was resolved that I should first go ashore with four machine guns and on leaving the General said "You've got your chance now, Wallingford let us see what you can do with it."

"I went ashore with four guns at 10 a.m. and we pushed on up to Plugge's Plateau. What struck me most was the fact that the men took no notice of the bullets, and also that we had landed at a small place for storing ammunition and supplies. One could not help being struck also, even amidst all the excitement, with the almost callous attitude of the midshipmen of the Navy. Here were these lads, mere boys, most of them, each in charge of a barge full of soldiers, plying in and out as indifferent to the storm of lead as if they were at a picnic. It was a sight to put heart into all.

"Once into action the cry was for reinforcements and consequently it had to be decided whether I should go on with the four guns or remain and wait for the lot (twelve). It was decided that I should wait and when the Otago Battalion came ashore we pushed on to Walker's Ridge, getting there about 3 p.m. The General afterwards decided to have the Otago Battalion back across Plugge's Plateau and he asked me how long it would take me. I said 'Twenty minutes.' He said 'You're a marvel if you can do it in an hour.' He forgot I had a megaphone and what gallant lads the Otago boys were proving themselves that day. I had them back in twenty-five minutes. The men worked like mules, it was heroic, and during the operation I think we experienced the hardest ten minutes' shrapnel fire it has ever been my lot to encounter. It was landing at the rate of twenty-six in ten seconds. At the conclusion of the operation the General said 'Well done, Wallingford.'

"Owing to persistent counter-attacks Colonel Brown, at 7 p.m., sent down for reinfoicements and two companies of the Canterbury Battalion, under Major (now Lieutenant-Colonel) Loach and Major Row came ashore. The beach was so full of dead and wounded that the men were compelled to fall in in the water. The things that struck me that day were the gallant conduct of the colonials, their fortitude under wounds, the ability with which they adapted themselves to the fighting and their unswerving promptitude in carrying out the most dangerous of orders."

MAJOR F. BROWN'S IMPRESSIONS.

On the morning of April 24 General Godley gave a lecture to the officers, at which a general outline of the campaign was unfolded. The main features were that the colonials were to go inland a little way, turn south and join forces with the English party that had landed at Cape Helles.

"The Hon. Edwards also gave a lecture to the officers, explaining the general temperament of the Turks and the sort of proposition we were up against. He explained that they were purely fatalists, and depended on the good Allah to perform some miracle. But he was convinced that with the army that he had seen in Egypt we were a match for them.

"During the trip over from Alexandria, when our men felt that they were really in for it, there was a vast improvement in the discipline and comradeship of all ranks.

"We held disembarkation practice in Mudros Bay, going down rope ladders into barges, and so on, and its use was proved fully later on. Our actual landing took place about 10 a.m. on Sunday. April 25, when our frontage was immediately changed to a left direction. We pushed up over what is known as Plugge's Plateau, on the far side of which was a deep ravine, known as Mine Gully, in which it had been reported that land mines had been laid. General Walker issued orders that this valley had to be avoided, which meant that our front had to go still further left. However, a small party of us pushed through this gully, one of the most memorable incidents being the courageous way in winch Major Grant took the small party through it. He was a man without fear, and simply looked for mines. Later in the same day he was killed; a very gallant soldier.

"Our destination, which was over tne third face, was reached by a small party of eight men and two officers, and to gain this position we had to push on under shrapnel and snipers' fire. We were then on the extreme left of the line and the fire was too hot to allow us to dig in, so we had to lie flat and try to defend our position as well as we could. The enemy came round on our flank and made things very warm with enfilading tire. We remained there until dusk, when we crept back and joined up with the main line. While we were in this position the Turks were often only a matter of ten yards from us, scrub being our only cover.

"I was bringing a party or stretcher-bearers up during the same day, when they were surprised and fired on. I was leading the party when the lurks opened fire at short range and worked havoc among our men. However, we managed to get out of it, and when night fell rain came on, and we had a miserable time, most of the men being very thirsty, as they had given their water away to the wounded.

"If you asked me what impressed me most that day, I would say that it was the calmness, the sense of having work to do and bucking into it that prevailed all through our lines during the fierce attack. The cool, calm and collected manner in which the men went over Walker's Ridge under that murderous rain of shrapnel, and in the face of snipers' fire from every quarter, is a thing that one who witnessed it will never have effaced from his memory.

AN OFFICER'S DIPBE3SIONS.

"It just seems like a vivid dream to me now as I sit and ponder over my diary, which I kept up to date from the day the Main Body left Wellington. The following are some of my impressions of that now famous day.

"April 20, 1915 - A feeling of suppressed excitement came over me as the troopship Lutzow crept slowly up the coast towards our goal. Orders were out for the landing of the Canterbury Infantry Battalion, 1st and 2nd Companies, at an early hour in the morning. The glorious Third Australian Brigade had just landed. They were given the task of clearing the beach for us, «ind the whole world knows how they did it. I saw it and saw the result, the beach was literally covered with dead and dying; it was a sight never to be forgotten.

"We were towed towards the beach by a naval steam launch, and then cast adrift just before our great barge, packed with men, bumped up against submerged rocks and huge stones, which kept us quite a long way from the shore. Everyone hesitated. All seemed uncertain for the moment what to do next, until an Australian staff officer on the beach shouted, "You are not frightened of the water, are you, New Zealand." Somehow I believe that is what we were frightened of, certainly not of the Turks or their shrapnel, which was constantly bursting over us, the bullets sprinkling the water like a hailstorm.

"We jumped into the water waist-deep and waded ashore with rifles held high above our heads. We charged up the side of the hill, over the top of dead, dying, friend and foe alike, with bullets dropping all around us with a dull thud, which gave one the creeps when one thought of the mission they were sent on. The whistle of the bullets passing by, mingled with the crash of bursting shrapnel, made our nerves jump a bit, for we had never before been subjected to such abuse as this, but there is an old soldier's saying, "You never hear the bullet that hits you."

"The wounded being carried to the rear, Australians and New Zealanders alike, were heroes, cheerfully bearing their pain, smoking cigarettes and joking with each other. One of my boys was hit with a bullet just above the heart, and when he saw me he said, with an effort, "They have got me this time," but I cheered him up, and told him he would be well enough to return to the fight very soon. I am pleased to relate he did recover and returned to the front, but it was too much for him, and he is now back in New Zealand."

SERGEANT RODGER, D.C.M.

"Being asked to give my impressions of that memorial day when the New Zealand Infantry Brigade landed on Gallipoli, one regrets that the first serious campaign that the Australasian forces were called on to carry through was destined to end in failure. Looking back to those stirring days and remembering those who ungrudgingly laid down their lives in the call of duty, one's thoughts are flooded with admiration and deepest sorrow.

"Embarked at Alexandria, I found that we had some two thousand odd aboard, including the New Zealand General Headquarters Staff. It was fine to note the good comradeship which grew among all ranks on board during the few days prior to the landing. To a stranger looking on, he would have thought by the cheery spirit of all on board it was a peaceful mission we were engaged on, instead of what Lord Kitchener described as one of the most important issues of the war.

"It was a most impressive sight to see the fleet steam out of Mudros Bay on the evening of the 24th, and one must have realised that with every other transport carrying a similar complement to our own the serious business was at hand. At dawn on the 25th the warships could be seen cannonading at the entrance to the Narrows, and it was there that the British troops effected a landing under the greatest difficulties. Too much praise cannot be given to the 29th Division for their deeds that day in landing at a strongly fortified place. Arriving at what is now known as Anzac Cove, we could see the Australians driving the enemy back from the beach and we were enabled to land under the minimum amount of fire.

"Once ashore we saw a steady stream of wounded being brought down from the hills, and the dressing stations were already full. Divesting ourselves of our packs we started to reinforce the Australians, and owing to the dense scrub it was impossible for the officers to keep their units intact, and once in the fire line every regiment was hopelessly mixed. We got straight to it, and it was not long before our rifle barrels were hot. It was grand to be fighting shoulder to shoulder with the Australian lads.

"As night fell we realised we had a bitter job in front of us, which soon proved to be the case once it was dark. The enemy made several advances, but the glow of our bayonets showing over our parapet evidently made them think twice. A heavy downpour of rain added to our discomforts during that night. A feat that strongly impressed me was the manner in which the stretcher bearers performed their duties. To carry wounded men from the fire line over those hills was a severe task, but our bearers never despaired. Word reached us that the Canterbury colonel had been killed. We cast doubts on the report, but an Australian who described the man and the way in which he died left no doubt as to it being our esteemed Colonel Stewart.

"With the twelve months elapsed and many more heavy engagements having taken place, severe gaps have been made in the ranks of that landing party, but if one was to be given the same task again I don't think there would be any dissenters, providing we could go into action with the same comrades."

A VIVID EXPERIENCE.

When I take my memory back and let it dwell on what occurred on Sunday, April 25, 1915 (Anzac Day), I find that: I have many vivid and unforgettable impressions, but when I come to try and write about them in a tangible way the task is not so easy as it first appeared. I think my first feeling on landing at the Dardanelles was the same as most of the boys felt, and that was a sense of having received something which we had worked and waited months for, and that we could no longer be called "tin soldiers," but were into the real thing at last. But to see dead and wounded men about soon drives these every-day thoughts out of your head, and the seriousness of war is brought home to you with the grim help of flying shrapnel and bullets.

The men start to look at each other, to see how everybody is taking this new experience, and their faces gradually lose the "civilian" look and become set into an expression which nobody but a soldier in action would have. I remember, towards afternoon, when I was lying in the firing line, the particular ridge I was on came in for some very heavy shell fire, from which we had no protection, besides, a rifle and machine gun fire, which made the question of keeping your head down a very vital one.

It was then that I had most of my sensations. To have the heavy brass cap of a shell land into the ground with a vicious thud near enough for bits of earth it throws up to hit you, makes you feel that there is quite a possibility of the next one finding the small of your back for a resting place, and the consequence is every shell you hear coming gives you peculiar feelings up the spine until it lands. My nerves were so tense that when a bullet marvellously landed in the heel of my boot, without scratching me, my whole body was jarred, and I was quite sure my foot was shattered, or something similar. In fact, I told the fellow next to me that I had stopped one, and he wanted to crawl over to me to do the first aid act. Four or five days later, when I had an opportunity, I took off my boot and found a bullet neatly embedded in the thick leather of the heel.

Of course, on that first day we were all new to actual fighting (for the action on the Suez Canal did not give us much experience), so perhaps everything seemed magnified. Later on we had some very severe fighting, but I think that if any man who was in the landing was asked what he thought were the worst days on the Peninsula he would, after a little thought, first two or three days.- Sergeant F. S. Dyer, Canterbury Regiment, Main Body.

SERGEANT R. G. RITCHIE.

"Fortunately for all concerned, on the evening of April 24, 1915, very few realised the immensity of the task that the following day was to bring, otherwise the chances are that the men would have gone into their task with more care than that dare-devil spirit which was shown by the colonials. It is true that we were all warned as to the gravity of our undertaking, but, with the good spirit prevailing among the men, the realisation of the message given to us by our general never dawned until after a good twenty-four hours of our actual landing. We steamed out of Mudros Bay at dusk on the Saturday evening. Orders were issued for every man to take as much rest as he possibly could, and in consequence the majority retired.

"I was awakened at 3 a.m. on that memorable day by the roar of our fleet's guns, battering at the forts of Kum Kale, and making a passage for the 'Glorious 29th Division.' It was then dark, and all that could be seen was the flash from the ships' guns and this alone made one realise that he was soon to experience his real baptism of fire. Steaming past this spot, we had another quiet hour until daylight. Then we could see several more transports ahead of us, some at anchor and others falling into place. Mingled with these were a number of warships, which were belching out death to the enemy ashore. We knew we had come to the place where we were to land. Coming in closer to the squadron and taking up our position, we soon learnt that the first part (the never-to-be-forgotten 3rd Australian Brigade) had already placed foot on Turkish soil. Between the roar of the ships' guns we could hear tho rattle of musketry, and this alone made us anxious to be alongside our comrades and doing our bit.

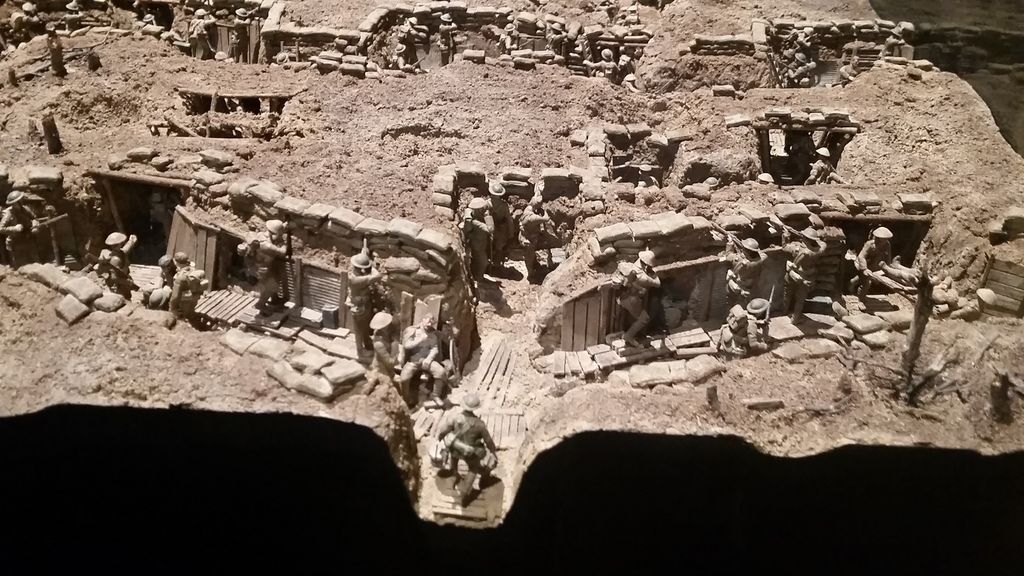

"At about 10 a.m., barges were alongside, and we were soon aboard them, and being towed to shore. Once ashore packs were discarded, and we went forward as hard as possible to join the Australians, who were driving the enemy before them. At about midday we reached the third ridge, and found the Australians occupying a trench which they had taken, and here we established ourselves. This same place proved to be a 'home' for many of us for many weeks after, for it was the position from which Quinn's Post grew. One point that impressed me was the apparent curiosity shown by our boys to the first few shrapnel shells which burst over our heads. Hearing the hissing sound made by the travelling shells nearly everyone would look up with wonder. I heard one chap say to his mate. 'I bet you don't know where the next one is going to burst,' and I think this will give the readers an idea of tho apparent careless feeling of our chaps.

"Many were wounded round about me that day, but it was glorious to see and now to realise the way those boys bore up. Wounds of every description were there, but you would never hear a murmur. It was the sufferer's main object not to be a burden to his comrades and to get back to a place where those appointed for attending him could look to him. Throughout the day and night the ambulance worked unfailingly, and no praise is too good for their heroic work. Night fell, and our positions were unchanged, and with the dark came rain, which fell periodically till morning, and added further discomforts to our load. It was truly grand to see the good fellowship that existed between the chaps in that struggle, and I think every survivor would make a big sacrifice if to-day he could meet the man who fought alongside him on April 25, 1915. Without a word about our English friends, who were similarly struggling at Cape Helles, it would be unjust to conclude. I had the pleasure of meeting a good number of them a few weeks later, and I am convinced that their task was equally as hard as ours, and their comradeship to us just as deep as ours to them. My strongest impression of this day twelve months ago was the undying, unflinching and merry spirit shown by our boys throughout the struggle."

SERGEANT HENRY BECK.

The morning of April 25, 1915, was beautifully fine, with the sun beating down on the boatloads of troops as they approached the now famous Gallipoli Peninsula. Not a soul spoke — the silence was oppressive, when, as if by prearranged signal, the Turks cunningly concealed on the heights opened up a murderous fire on the boats. The shooting was fairly accurate, and naturally speed was increased, and at the same time our ever watchful warships poured a hail of shells on the enemy. The thunder of the cannon, the sharper cough of the machine guns and the crack of the rifles made an awful din. Shells burst over our heads with deafening report. Man after man flung up his hands and died, died without firing a shot. It was devilish sitting hunched up in the boats, seeing no one, yet our mates were dropping every second; it was maddening sitting inactive.

"Knowing that we were powerless until we could land, we cursed our impotence, the Turks, the slowness of our boats, in fact, everything in general. At last the shallows were reached and we plunged into the sea, some breast high, and made for the shore. We waited for no orders, our destination was the top of the cliff and we meant to get there. On all sides men dropped, and we who were spared climbed madly upwards. At last, waiting for breath, we reached the top, and went forward to meet the Turks.

"Australians ran shoulder to shoulder with New Zealanders, men from all companies were intermingled. It was no time for review older, we were at war, out to kill or be killed. We were not men for the time, but simply raging animals lusting for blood. We fought tooth and nail. The Turks fled screaming from their trench. In full pursuit we were at them, driving them far beyond. We soon became fatigued and some were practically exhausted. Finally the mad scramble ceased and we guessed we were roughly two miles inland. By nightfall we had improvised a sort of trench, but were continually harassed by the Turks, who repeatedly endeavoured to dislodge us.

"We had in Egvpt several times toasted, and boasted of the day, and we had it! We, the callow, inexperienced colonials, had proved ourselves as fighters. And now, how bitter is the realisation that our sacrifice was practically in vain. To know that hundreds of our comrades who lie buried on Gallipoli died for nothing. However, to repent is useles, we can but console ourselves with the knowledge that we did what was asked of us."

CANTERBURY BOY'S STORY.

"The day selected for the landing was one of these glorious fresh days that we have been experiencing locally lately. The troops were early astir without knowing exactly what to anticipate. Away in the distance the Navy's bombardment of Cape Helles was in full play and from posts on the boat deck we could see the shells bursting all over the slopes of Achi Baba and on the forts at Seddel Bahr — it was a wonderful sight that made a great impression upon us all.

"As we steamed up to Anzac about 7 a.m. the landing was in full swing — a fleet of steam pinnaces was rushing ships' boats and lighters packed with Australians inshore as rapidly as possible, whilst from the hills in front came the crack of rifles and the crack crack of machine guns, punctuated by bursts of Turkish shrapnel and high explosive. At 7.30 a.m our disembarkation commenced, the Aucklanders being the first New Zealand troops ashore, followed by the 1st and '2nd Canterbury Companies. I shall never forget the experience of those next hours. We scrambled down the rope ladders and filled the lighters as rapidly as possible. Within a few minutes we were under way and running for the shore. Everyone sat up watching events ahead, thrilled and elated that the hour for action had at last come. It seemed no time before we had leapt out of the boat and were wading ashore waist deep. The company was formed up on the beach, packs were stowed, a party detailed to pick up ammunition and away we went to lend a hand in the firing line.

"What were my feelings? Certainly some perplexity, coupled with an ardent desire to do something real, now that the opportunity had come. As I look back upon that morning, I am thrilled with admiration for the wonderful spirit that sustained, our men in the first big test. Everyone was in the rush — all the best that a healthy colonial life had taught came to the surface and carried us through. Nothing else could have done it.

"On the top of the first hill we came under heavy shrapnel fire that penetrated every inch of cover. There seemed to be no escape from it. We turned over the rise and up the gully, meeting dozens of wounded Australians at the dressing stations. On the left urgent messages were being signalled for reinforcements. There was no time to delay so away we went, up and up. It seemed an endless climb through dense bush and muddy streams. Just under the crest of the second hill we halted for a breather and counted the party fourteen in all. A mad medley of noise, the cracking of rifles, the belching of mountain batteries, and the groaning of men, disclosed the firing line a few yards beyond. By general consent we decided to issue forth for the last dash, in three parties, and away went the first. It is not pleasant to recollect the experience of that break for the line. We had barely covered ten yards when the first man went and we dropped beside him. We had seen the beach strewn with dead, men lying in every gully and on every slope over the two miles that we had covered, but we did not understand, till then. In the line I came upon two Australians who took me up, gave the range, direction, and proceeded to initiate me. 'We'll show you — four rounds rapid,' and with amazing steadiness they rose to their knees, sighted their object and fired. When the four rounds were expended they took cover, reloaded and gathered me in. Thus I was converted to an intense admiration for these noble, gallant fighters. It was hot work, the real thing. Men were falling everywhere, and no reinforcements coming forward. At four o'clock the enemy pushed back our left and had us enfiladed. The fight had reached a climax. The air was simply living with lead. In the space of seconds I had lost my two Australian heroes and had been christened myself. What to do? Out of the din came the order to retire to the ridge, and as we rose the whole of the enemy fire was concentrated upon us. How anyone survived it I cannot hope to explain. For myself I staggered into safety with more prayers of thankfulness than I had ever known."

A YEAR AGO

During the past few days representatives of the "Star" have interviewed several officers and men who took part in the famous landing a year ago today. The accounts obtained afford interesting glimpses of stirring events and, in many ways, bring home the difficulties of that magnificent military venture.

CAPTAIN WALLINGFORD, M.C.

The nation knows of Captain Wallingford, one of the best shots the British Army has ever turned out, who was in charge of New Zealand's machine guns at the landing and after an arduous and brilliant campaign was invalided and received the Military Cross. Captain Wallingford, who joined New Zealand's Main Body from the position of musketry instructor in tho Auckland military district, was in Christchurch a few days ago and a "Star" reporter was lucky enough to run across him just before he left again for the north. In a very hurried interview Captain Wallingford gave his impressions of a year ago to-day.

"Very early on the morning of Sunday. April 25, 1915, it having been decided to land on one of the beaches, I was called to a conference with General Godley and I was there four hours. It was resolved that I should first go ashore with four machine guns and on leaving the General said "You've got your chance now, Wallingford let us see what you can do with it."

"I went ashore with four guns at 10 a.m. and we pushed on up to Plugge's Plateau. What struck me most was the fact that the men took no notice of the bullets, and also that we had landed at a small place for storing ammunition and supplies. One could not help being struck also, even amidst all the excitement, with the almost callous attitude of the midshipmen of the Navy. Here were these lads, mere boys, most of them, each in charge of a barge full of soldiers, plying in and out as indifferent to the storm of lead as if they were at a picnic. It was a sight to put heart into all.

"Once into action the cry was for reinforcements and consequently it had to be decided whether I should go on with the four guns or remain and wait for the lot (twelve). It was decided that I should wait and when the Otago Battalion came ashore we pushed on to Walker's Ridge, getting there about 3 p.m. The General afterwards decided to have the Otago Battalion back across Plugge's Plateau and he asked me how long it would take me. I said 'Twenty minutes.' He said 'You're a marvel if you can do it in an hour.' He forgot I had a megaphone and what gallant lads the Otago boys were proving themselves that day. I had them back in twenty-five minutes. The men worked like mules, it was heroic, and during the operation I think we experienced the hardest ten minutes' shrapnel fire it has ever been my lot to encounter. It was landing at the rate of twenty-six in ten seconds. At the conclusion of the operation the General said 'Well done, Wallingford.'

"Owing to persistent counter-attacks Colonel Brown, at 7 p.m., sent down for reinfoicements and two companies of the Canterbury Battalion, under Major (now Lieutenant-Colonel) Loach and Major Row came ashore. The beach was so full of dead and wounded that the men were compelled to fall in in the water. The things that struck me that day were the gallant conduct of the colonials, their fortitude under wounds, the ability with which they adapted themselves to the fighting and their unswerving promptitude in carrying out the most dangerous of orders."

MAJOR F. BROWN'S IMPRESSIONS.

On the morning of April 24 General Godley gave a lecture to the officers, at which a general outline of the campaign was unfolded. The main features were that the colonials were to go inland a little way, turn south and join forces with the English party that had landed at Cape Helles.

"The Hon. Edwards also gave a lecture to the officers, explaining the general temperament of the Turks and the sort of proposition we were up against. He explained that they were purely fatalists, and depended on the good Allah to perform some miracle. But he was convinced that with the army that he had seen in Egypt we were a match for them.

"During the trip over from Alexandria, when our men felt that they were really in for it, there was a vast improvement in the discipline and comradeship of all ranks.

"We held disembarkation practice in Mudros Bay, going down rope ladders into barges, and so on, and its use was proved fully later on. Our actual landing took place about 10 a.m. on Sunday. April 25, when our frontage was immediately changed to a left direction. We pushed up over what is known as Plugge's Plateau, on the far side of which was a deep ravine, known as Mine Gully, in which it had been reported that land mines had been laid. General Walker issued orders that this valley had to be avoided, which meant that our front had to go still further left. However, a small party of us pushed through this gully, one of the most memorable incidents being the courageous way in winch Major Grant took the small party through it. He was a man without fear, and simply looked for mines. Later in the same day he was killed; a very gallant soldier.

"Our destination, which was over tne third face, was reached by a small party of eight men and two officers, and to gain this position we had to push on under shrapnel and snipers' fire. We were then on the extreme left of the line and the fire was too hot to allow us to dig in, so we had to lie flat and try to defend our position as well as we could. The enemy came round on our flank and made things very warm with enfilading tire. We remained there until dusk, when we crept back and joined up with the main line. While we were in this position the Turks were often only a matter of ten yards from us, scrub being our only cover.

"I was bringing a party or stretcher-bearers up during the same day, when they were surprised and fired on. I was leading the party when the lurks opened fire at short range and worked havoc among our men. However, we managed to get out of it, and when night fell rain came on, and we had a miserable time, most of the men being very thirsty, as they had given their water away to the wounded.

"If you asked me what impressed me most that day, I would say that it was the calmness, the sense of having work to do and bucking into it that prevailed all through our lines during the fierce attack. The cool, calm and collected manner in which the men went over Walker's Ridge under that murderous rain of shrapnel, and in the face of snipers' fire from every quarter, is a thing that one who witnessed it will never have effaced from his memory.

AN OFFICER'S DIPBE3SIONS.

"It just seems like a vivid dream to me now as I sit and ponder over my diary, which I kept up to date from the day the Main Body left Wellington. The following are some of my impressions of that now famous day.

"April 20, 1915 - A feeling of suppressed excitement came over me as the troopship Lutzow crept slowly up the coast towards our goal. Orders were out for the landing of the Canterbury Infantry Battalion, 1st and 2nd Companies, at an early hour in the morning. The glorious Third Australian Brigade had just landed. They were given the task of clearing the beach for us, «ind the whole world knows how they did it. I saw it and saw the result, the beach was literally covered with dead and dying; it was a sight never to be forgotten.

"We were towed towards the beach by a naval steam launch, and then cast adrift just before our great barge, packed with men, bumped up against submerged rocks and huge stones, which kept us quite a long way from the shore. Everyone hesitated. All seemed uncertain for the moment what to do next, until an Australian staff officer on the beach shouted, "You are not frightened of the water, are you, New Zealand." Somehow I believe that is what we were frightened of, certainly not of the Turks or their shrapnel, which was constantly bursting over us, the bullets sprinkling the water like a hailstorm.

"We jumped into the water waist-deep and waded ashore with rifles held high above our heads. We charged up the side of the hill, over the top of dead, dying, friend and foe alike, with bullets dropping all around us with a dull thud, which gave one the creeps when one thought of the mission they were sent on. The whistle of the bullets passing by, mingled with the crash of bursting shrapnel, made our nerves jump a bit, for we had never before been subjected to such abuse as this, but there is an old soldier's saying, "You never hear the bullet that hits you."

"The wounded being carried to the rear, Australians and New Zealanders alike, were heroes, cheerfully bearing their pain, smoking cigarettes and joking with each other. One of my boys was hit with a bullet just above the heart, and when he saw me he said, with an effort, "They have got me this time," but I cheered him up, and told him he would be well enough to return to the fight very soon. I am pleased to relate he did recover and returned to the front, but it was too much for him, and he is now back in New Zealand."

SERGEANT RODGER, D.C.M.

"Being asked to give my impressions of that memorial day when the New Zealand Infantry Brigade landed on Gallipoli, one regrets that the first serious campaign that the Australasian forces were called on to carry through was destined to end in failure. Looking back to those stirring days and remembering those who ungrudgingly laid down their lives in the call of duty, one's thoughts are flooded with admiration and deepest sorrow.

"Embarked at Alexandria, I found that we had some two thousand odd aboard, including the New Zealand General Headquarters Staff. It was fine to note the good comradeship which grew among all ranks on board during the few days prior to the landing. To a stranger looking on, he would have thought by the cheery spirit of all on board it was a peaceful mission we were engaged on, instead of what Lord Kitchener described as one of the most important issues of the war.

"It was a most impressive sight to see the fleet steam out of Mudros Bay on the evening of the 24th, and one must have realised that with every other transport carrying a similar complement to our own the serious business was at hand. At dawn on the 25th the warships could be seen cannonading at the entrance to the Narrows, and it was there that the British troops effected a landing under the greatest difficulties. Too much praise cannot be given to the 29th Division for their deeds that day in landing at a strongly fortified place. Arriving at what is now known as Anzac Cove, we could see the Australians driving the enemy back from the beach and we were enabled to land under the minimum amount of fire.

"Once ashore we saw a steady stream of wounded being brought down from the hills, and the dressing stations were already full. Divesting ourselves of our packs we started to reinforce the Australians, and owing to the dense scrub it was impossible for the officers to keep their units intact, and once in the fire line every regiment was hopelessly mixed. We got straight to it, and it was not long before our rifle barrels were hot. It was grand to be fighting shoulder to shoulder with the Australian lads.

"As night fell we realised we had a bitter job in front of us, which soon proved to be the case once it was dark. The enemy made several advances, but the glow of our bayonets showing over our parapet evidently made them think twice. A heavy downpour of rain added to our discomforts during that night. A feat that strongly impressed me was the manner in which the stretcher bearers performed their duties. To carry wounded men from the fire line over those hills was a severe task, but our bearers never despaired. Word reached us that the Canterbury colonel had been killed. We cast doubts on the report, but an Australian who described the man and the way in which he died left no doubt as to it being our esteemed Colonel Stewart.

"With the twelve months elapsed and many more heavy engagements having taken place, severe gaps have been made in the ranks of that landing party, but if one was to be given the same task again I don't think there would be any dissenters, providing we could go into action with the same comrades."

A VIVID EXPERIENCE.

When I take my memory back and let it dwell on what occurred on Sunday, April 25, 1915 (Anzac Day), I find that: I have many vivid and unforgettable impressions, but when I come to try and write about them in a tangible way the task is not so easy as it first appeared. I think my first feeling on landing at the Dardanelles was the same as most of the boys felt, and that was a sense of having received something which we had worked and waited months for, and that we could no longer be called "tin soldiers," but were into the real thing at last. But to see dead and wounded men about soon drives these every-day thoughts out of your head, and the seriousness of war is brought home to you with the grim help of flying shrapnel and bullets.

The men start to look at each other, to see how everybody is taking this new experience, and their faces gradually lose the "civilian" look and become set into an expression which nobody but a soldier in action would have. I remember, towards afternoon, when I was lying in the firing line, the particular ridge I was on came in for some very heavy shell fire, from which we had no protection, besides, a rifle and machine gun fire, which made the question of keeping your head down a very vital one.

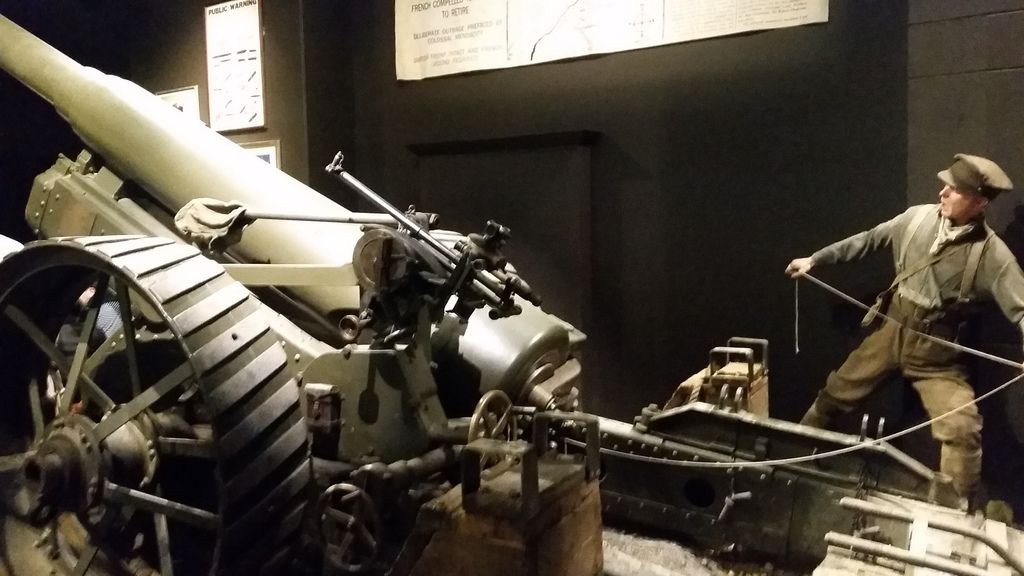

It was then that I had most of my sensations. To have the heavy brass cap of a shell land into the ground with a vicious thud near enough for bits of earth it throws up to hit you, makes you feel that there is quite a possibility of the next one finding the small of your back for a resting place, and the consequence is every shell you hear coming gives you peculiar feelings up the spine until it lands. My nerves were so tense that when a bullet marvellously landed in the heel of my boot, without scratching me, my whole body was jarred, and I was quite sure my foot was shattered, or something similar. In fact, I told the fellow next to me that I had stopped one, and he wanted to crawl over to me to do the first aid act. Four or five days later, when I had an opportunity, I took off my boot and found a bullet neatly embedded in the thick leather of the heel.

Of course, on that first day we were all new to actual fighting (for the action on the Suez Canal did not give us much experience), so perhaps everything seemed magnified. Later on we had some very severe fighting, but I think that if any man who was in the landing was asked what he thought were the worst days on the Peninsula he would, after a little thought, first two or three days.- Sergeant F. S. Dyer, Canterbury Regiment, Main Body.

SERGEANT R. G. RITCHIE.

"Fortunately for all concerned, on the evening of April 24, 1915, very few realised the immensity of the task that the following day was to bring, otherwise the chances are that the men would have gone into their task with more care than that dare-devil spirit which was shown by the colonials. It is true that we were all warned as to the gravity of our undertaking, but, with the good spirit prevailing among the men, the realisation of the message given to us by our general never dawned until after a good twenty-four hours of our actual landing. We steamed out of Mudros Bay at dusk on the Saturday evening. Orders were issued for every man to take as much rest as he possibly could, and in consequence the majority retired.

"I was awakened at 3 a.m. on that memorable day by the roar of our fleet's guns, battering at the forts of Kum Kale, and making a passage for the 'Glorious 29th Division.' It was then dark, and all that could be seen was the flash from the ships' guns and this alone made one realise that he was soon to experience his real baptism of fire. Steaming past this spot, we had another quiet hour until daylight. Then we could see several more transports ahead of us, some at anchor and others falling into place. Mingled with these were a number of warships, which were belching out death to the enemy ashore. We knew we had come to the place where we were to land. Coming in closer to the squadron and taking up our position, we soon learnt that the first part (the never-to-be-forgotten 3rd Australian Brigade) had already placed foot on Turkish soil. Between the roar of the ships' guns we could hear tho rattle of musketry, and this alone made us anxious to be alongside our comrades and doing our bit.

"At about 10 a.m., barges were alongside, and we were soon aboard them, and being towed to shore. Once ashore packs were discarded, and we went forward as hard as possible to join the Australians, who were driving the enemy before them. At about midday we reached the third ridge, and found the Australians occupying a trench which they had taken, and here we established ourselves. This same place proved to be a 'home' for many of us for many weeks after, for it was the position from which Quinn's Post grew. One point that impressed me was the apparent curiosity shown by our boys to the first few shrapnel shells which burst over our heads. Hearing the hissing sound made by the travelling shells nearly everyone would look up with wonder. I heard one chap say to his mate. 'I bet you don't know where the next one is going to burst,' and I think this will give the readers an idea of tho apparent careless feeling of our chaps.

"Many were wounded round about me that day, but it was glorious to see and now to realise the way those boys bore up. Wounds of every description were there, but you would never hear a murmur. It was the sufferer's main object not to be a burden to his comrades and to get back to a place where those appointed for attending him could look to him. Throughout the day and night the ambulance worked unfailingly, and no praise is too good for their heroic work. Night fell, and our positions were unchanged, and with the dark came rain, which fell periodically till morning, and added further discomforts to our load. It was truly grand to see the good fellowship that existed between the chaps in that struggle, and I think every survivor would make a big sacrifice if to-day he could meet the man who fought alongside him on April 25, 1915. Without a word about our English friends, who were similarly struggling at Cape Helles, it would be unjust to conclude. I had the pleasure of meeting a good number of them a few weeks later, and I am convinced that their task was equally as hard as ours, and their comradeship to us just as deep as ours to them. My strongest impression of this day twelve months ago was the undying, unflinching and merry spirit shown by our boys throughout the struggle."

SERGEANT HENRY BECK.

The morning of April 25, 1915, was beautifully fine, with the sun beating down on the boatloads of troops as they approached the now famous Gallipoli Peninsula. Not a soul spoke — the silence was oppressive, when, as if by prearranged signal, the Turks cunningly concealed on the heights opened up a murderous fire on the boats. The shooting was fairly accurate, and naturally speed was increased, and at the same time our ever watchful warships poured a hail of shells on the enemy. The thunder of the cannon, the sharper cough of the machine guns and the crack of the rifles made an awful din. Shells burst over our heads with deafening report. Man after man flung up his hands and died, died without firing a shot. It was devilish sitting hunched up in the boats, seeing no one, yet our mates were dropping every second; it was maddening sitting inactive.

"Knowing that we were powerless until we could land, we cursed our impotence, the Turks, the slowness of our boats, in fact, everything in general. At last the shallows were reached and we plunged into the sea, some breast high, and made for the shore. We waited for no orders, our destination was the top of the cliff and we meant to get there. On all sides men dropped, and we who were spared climbed madly upwards. At last, waiting for breath, we reached the top, and went forward to meet the Turks.

"Australians ran shoulder to shoulder with New Zealanders, men from all companies were intermingled. It was no time for review older, we were at war, out to kill or be killed. We were not men for the time, but simply raging animals lusting for blood. We fought tooth and nail. The Turks fled screaming from their trench. In full pursuit we were at them, driving them far beyond. We soon became fatigued and some were practically exhausted. Finally the mad scramble ceased and we guessed we were roughly two miles inland. By nightfall we had improvised a sort of trench, but were continually harassed by the Turks, who repeatedly endeavoured to dislodge us.

"We had in Egvpt several times toasted, and boasted of the day, and we had it! We, the callow, inexperienced colonials, had proved ourselves as fighters. And now, how bitter is the realisation that our sacrifice was practically in vain. To know that hundreds of our comrades who lie buried on Gallipoli died for nothing. However, to repent is useles, we can but console ourselves with the knowledge that we did what was asked of us."

CANTERBURY BOY'S STORY.

"The day selected for the landing was one of these glorious fresh days that we have been experiencing locally lately. The troops were early astir without knowing exactly what to anticipate. Away in the distance the Navy's bombardment of Cape Helles was in full play and from posts on the boat deck we could see the shells bursting all over the slopes of Achi Baba and on the forts at Seddel Bahr — it was a wonderful sight that made a great impression upon us all.

"As we steamed up to Anzac about 7 a.m. the landing was in full swing — a fleet of steam pinnaces was rushing ships' boats and lighters packed with Australians inshore as rapidly as possible, whilst from the hills in front came the crack of rifles and the crack crack of machine guns, punctuated by bursts of Turkish shrapnel and high explosive. At 7.30 a.m our disembarkation commenced, the Aucklanders being the first New Zealand troops ashore, followed by the 1st and '2nd Canterbury Companies. I shall never forget the experience of those next hours. We scrambled down the rope ladders and filled the lighters as rapidly as possible. Within a few minutes we were under way and running for the shore. Everyone sat up watching events ahead, thrilled and elated that the hour for action had at last come. It seemed no time before we had leapt out of the boat and were wading ashore waist deep. The company was formed up on the beach, packs were stowed, a party detailed to pick up ammunition and away we went to lend a hand in the firing line.

"What were my feelings? Certainly some perplexity, coupled with an ardent desire to do something real, now that the opportunity had come. As I look back upon that morning, I am thrilled with admiration for the wonderful spirit that sustained, our men in the first big test. Everyone was in the rush — all the best that a healthy colonial life had taught came to the surface and carried us through. Nothing else could have done it.

"On the top of the first hill we came under heavy shrapnel fire that penetrated every inch of cover. There seemed to be no escape from it. We turned over the rise and up the gully, meeting dozens of wounded Australians at the dressing stations. On the left urgent messages were being signalled for reinforcements. There was no time to delay so away we went, up and up. It seemed an endless climb through dense bush and muddy streams. Just under the crest of the second hill we halted for a breather and counted the party fourteen in all. A mad medley of noise, the cracking of rifles, the belching of mountain batteries, and the groaning of men, disclosed the firing line a few yards beyond. By general consent we decided to issue forth for the last dash, in three parties, and away went the first. It is not pleasant to recollect the experience of that break for the line. We had barely covered ten yards when the first man went and we dropped beside him. We had seen the beach strewn with dead, men lying in every gully and on every slope over the two miles that we had covered, but we did not understand, till then. In the line I came upon two Australians who took me up, gave the range, direction, and proceeded to initiate me. 'We'll show you — four rounds rapid,' and with amazing steadiness they rose to their knees, sighted their object and fired. When the four rounds were expended they took cover, reloaded and gathered me in. Thus I was converted to an intense admiration for these noble, gallant fighters. It was hot work, the real thing. Men were falling everywhere, and no reinforcements coming forward. At four o'clock the enemy pushed back our left and had us enfiladed. The fight had reached a climax. The air was simply living with lead. In the space of seconds I had lost my two Australian heroes and had been christened myself. What to do? Out of the din came the order to retire to the ridge, and as we rose the whole of the enemy fire was concentrated upon us. How anyone survived it I cannot hope to explain. For myself I staggered into safety with more prayers of thankfulness than I had ever known."