I just came across an article with a much later B-29 Superfortress visit to Whenuapai. This article from the Sunday Herald (NSW, Australia) dated the 5th of July 1953 mentions a visit on the 8th of October 1952.

U.S. MAY KNOW SOME OF OUR ATOM BOMB SECRETSBy A Special Correspondent

TESTS OF British atomic weapons In Australia have aroused intense interest in the United States, and almost certainly in Russia too. That interest will be increased by the announcement that further bomb tests are planned in South Australia. Security precautions have been stringent. How jar have they been successful? This article, the first of a series, suggests that the United States, at least, may have been able to gather considerable

information about our first A-Bomb explosion.IT is almost a year now since Britain exploded her first atomic bomb at the desolate uninhabited Monte Bello Islands, off the coast of Western Australia.

It will be remembered that the test was carried out in the greatest of secrecy. Security precautions were perhaps the strictest in Australia's peacetime history. Military and civil security men thoroughly investigated every one of the thousands of servicemen and scientists working on the project and combed the North-west Australian coastline for hundreds of miles north and south of the area.

Vast areas were declared prohibited or restricted. Wide air and sea patrols were carried out for weeks before and after the test. Britain pointedly and somewhat curtly denied observers from friendly Western powers the right to view the test.

The ReasonTHE decision not to allow friendly foreign observers to see the test probably stemmed from a certain amount of bitterness between the U.S. and Britain over the exchange of atomic secrets. During World War II, Britain and the U.S. pooled their atomic resources and knowledge and worked together to make a bomb with which to defeat Germany and Japan. Though Britain had her own establishments at home, these were closed and the cooperative work was done in America - far away from the danger of German bombers.

However, after the war it was discovered that both British and American traitors working on atomic projects had passed on vital information to Russia. The result of the subsequent uproar was that America barred the sharing of information - and Britain found herself in the unhappy position of having to start almost from scratch and set up her own scientific and productive organisation at home.

The world was staggered when Britain announced in 1951 that she was ready to test an atomic weapon. Most nations thought she was still years away from this goal. Soon after the announcement was made the U.S. offered Britain the use of one of her established testing grounds, but Britain politely

refused and set about establishing at a cost of millions, her own testing ground at the Monte Bellos.

But the precautions were not as effective as they seemed.

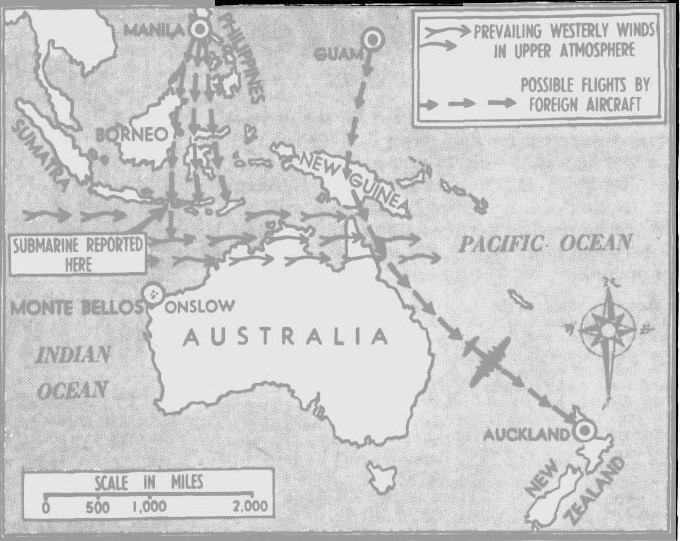

THERE is little doubt that United States aircraft operating in the North Australian area from Pacific bases flew through the dispersing atomic cloud from the Monte Bello explosion of October, 1952. It is probable, too, that from instrument recordings and observations made aboard these aircraft, the Americans were able to gain a wealth of information - information we did all in our power to keep to ourselves about the bomb.

How was it done? The map shows the answer.

It is not generally known that operating from carefully selected bases in the Pacific are patrols of specially equipped U.S. "atomic" Superfortress aircraft. These aircraft fly at varying heights over vast areas of the Pacific, and from recording instruments scientists are able to tell whether there are radio-active particles in the air which are a result of an atomic explosion.

This is part of a world-wide system which the United States instituted when it discovered that Russia had stolen the secret of the atom bomb.

WHEN an atomic explosion occurs, the radioactive atomic cloud shoots many thousands of feet into the air. Some of the radioactive particles fall back to earth, but a good deal of "dust" finds its way to the upper atmosphere. In the upper atmosphere the prevailing winds are always westerlies, and these atomic particles join others (the atmosphere is full of them) and are swept round the world from west to east. An atomic explosion in Russia, for instance, would inevitably send lots of radioactive particles into the upper atmosphere. The winds would sweep them west and it would not be long before the U.S. Pacific "atomic" patrol aircraft picked up the vital information on their sensitive instruments.

No doubt the Russians have their own special aircraft flying about in the upper atmosphere in their area, too.

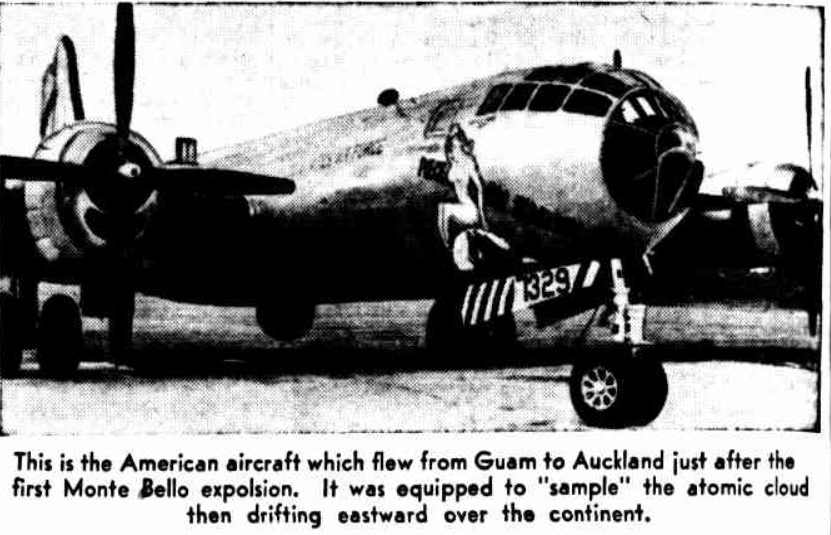

This is the American aircraft which flew from Guam to Auckland just after the first Monte Bello explosion. It was equipped to "sample" the atomic cloud then drifting eastward over the continent.

IT is possible, therefore, that both U.S. and Russian patrol aircraft picked up evidence of the Monte Bello explosion. But the important question

is this; How close did foreign aircraft get to the Monte Bello area? There is little doubt that American Superfortresses of the "atomic" patrols swept much further south than ever before.

It is quite possible that long range aircraft left Pacific bases soon after the explosion on October 3 last year and flew down near North Australia to intercept the cloud. Later, as the radioactive particles swept eastward in the upper atmosphere, aircraft could have intercepted the cloud (or particles) east of Australia, when it had travelled only about 2,000 miles.

On October 8 - five days after the explosion - a U.S. Superfortress arrived unexpectedly at Whenuapai Airport, Auckland. It observed strict radio silence until it was within half-an-hour of Auckland, when it asked for landing instructions. This was the first New Zealand civil aviation authorities knew of the flight.

A guard was placed on the aircraft immediately it landed. The crew members said they were on a "long-range training flight" and refused to answer questions about whether they had helped track the atomic cloud.

It was an interesting aircraft in more ways than one. A huge nude was painted on the side of the aircraft. Near the nude in large letters was the bomber's name-"Piece On Earth."

But observers who knew what to look for found something much more interesting. The aircraft carried filters (one of the methods of detecting in the air radioactive particles from an atomic explosion) under the fuselage and under each wing. Also, the aircraft had been modified to refuel aircraft in flight, and it carried a crew of 11, whereas the operational crew for the type is eight. The crew said the aircraft came from Guam Island, but would say no more. The aircraft left New Zealand the following day.

This is not proof positive that American aircraft tracked the cloud, but there was no denial of an Auckland report that "Piece On Earth" did, in fact, track and measure the dissipating Monte Bello cloud.

AIR samples taken from an atomic cloud would show a great deal. The checking aircraft carry special devices called "samplers" which pick up atmospheric dust at various altitudes and direct it on to photographic plates. Radio-active particles leave characteristic marks which identify them and though the atmosphere is naturally full of particles, the method is sufficiently sensitive to discover any additions caused by an atomic explosion.

There are other types of detecting and identifying equipment, too For instance, vast quantities of air are drawn through filters, which collect dust particles for later laboratory examinations. Not only the existence of the explosive can be discovered from these tests - the fissionable material also can be determined. Each material has its own characteristic proportions of the 60-odd primary fission products known, so careful measurement of the proportions indicates the bomb material.

The "Submarine"AN unidentified submarine was reported to have been seen about 700 miles from the Monte Bellos the night before the test When the British oil tanker Bela reached Darwin on October 10. Third Officer G. P. Windust reported that he had seen a submarine 800 miles west of Darwin at 10.30 pm on October 2.

He said that when the Bela (bound for Darwin from Singapore) was about 12 hours out of Bali in the Lombok Passage he saw a submarine ahead. 'It was a clear, moonlit night and I could see the conning tower clearly," said Mr Windust. "The submarine did not have navigation lights. I signalled it by Aldis lamp three times, but it didn't answer "

Normal practice at sea, even for naval vessels is to answer such signals. There is no record of this report having been corroborated and the alleged submarine was a long way from the Monte Bellos - probably too far away to gain much information from sea level if that was its object. But these days submarines can carry aircraft which can be taken back aboard after flight. If an aircraft did operate in this way, the power and effectiveness of the bomb could have been calculated with great accuracy.