|

|

Post by planewriting on Feb 3, 2022 14:13:50 GMT 12

In the August 1971 AHSNZ Journal Ross Dunlop wrote an article on Safe Air Ltd.

In part he wrote:

"To afford some relief to NAC, Safe Air sought charter aircraft in Australia, Britain and America, but without success. Finally, a short-term charter was arranged with Civil Air transport, an American-owned and Chinese registered airline based in Formosa.

Between April and July 1951 CAT made four Curtiss C-46 Commando aircraft available (XT-840, 844, 846 and 864 – the registration prefix was changed to B- during the latter part of their stay in New Zealand). The first two C-46s arrived at Paraparaumu on 12 April 1951 under CAT’s senior pilot, Captain Felix Smith, and the operations manager Mrs Olive King

The aircraft made their first trial flight across Cook Strait on 14 April when they flew from Woodbourne to Paraparaumu each with 14,000 lbs of malt. Regular operations started on the 16th. An additional reason for the trial flight was to enable the American pilots to qualify for a New Zealand licence endorsement.

The third C-46 arrived in New Zealand at the beginning of May. A fourth C-46 was also brought down from Hong Kong, but CAT generally only flew three a time. The C-46 was the largest twin-engined cargo aircraft in the world at the time and had a hold capacity of 2,300 cu.ft, twice that of a DC-3.

NAC, which at that time was operating two Dakotas on eight return flights each day, ceased flying the rail-air service on 5 May.

The CAT pilots were paid by the number of their flying hours and as a result the aircraft were in the air for seven days a week, making up to 11 return flights each day. Despite the fleet making 1300 crossings of Cook Strait (or 96,600 miles) and carrying 7800 tons of freight, the pilots were reported to have earned less money in New Zealand than in their normal Far East stamping grounds. This was mainly due to the short, half-hour flights across Cook Strait with an hour turn around in between.

Although the C-46s contributed a great deal in the shifting of piled-up cargo during their three months in New Zealand they were not entirely suitable for the rail-air service because their floor level was too high above the ground for ease of loading and unloading certain classes of freight.

Once the two Safe Air Freighters were introduced on May the need for the CAT aircraft diminished and their operations were gradually run down. The first C-46 left Woodbourne on 28 June for Brisbane with a full load of wool; the second aircraft flew to Auckland on 18 July awaiting the last two, which left Woodbourne on 23 July. The three left Auckland for Formosa on 27 July".

I am adding a few notes here of my own: The two NAC Dakotas were ZK-AOD and ZK-AOF which were then converted into DC-3 passenger airliners. A third one, ZK-AOE, had crashed on 9 August 1948 and what was originally intended to be a fourth one, ZK-AOG, was not required and had its registration cancelled only to surface soon after as freighter ZK-AQP. At the time of the C-46 operation the name SAFE AIR had not been adopted. The Bristols were with SAFE (Straits Air Freight Express).

|

|

|

|

Post by madmac on Feb 3, 2022 16:23:49 GMT 12

Now with that most informative lead-in from planewriting, here are some more of the NZR photos of freight operations of that period. First a few of the photos of sheep. Any one got anything on the attempts to air freight sheep, RNZ has a lot of photos of them being loaded, with some interesting changes in cabin details. There appears to been quite a bit of evolution there is a photo (which I can't find at the moment) of the sheep having canvas over their heads, then they appear to have used individual aperture cards in the windows, then some form of gill liner (which is the first thing I thought when I saw the first photo, I bet the apprentices wished they had gilliner to control some of the mess). For those that don't know, gilliner is a fibreglass flexible sheet used to protect the cabins of cargo aircraft from rash. All photos, New Zealand Railways Department National Archives [/a]  [/a]

|

|

|

|

Post by madmac on Feb 3, 2022 16:50:42 GMT 12

|

|

|

|

Post by Dave Homewood on Feb 3, 2022 17:40:56 GMT 12

Mark McGuire brought this news snippet to my attention from the PRESS, 24 MAY 1951

Cars Carried by Aircraft

Curtiss Commando aircraft began ferrying motor-cars between the North and South Islands yesterday. Six cars and 16 engines were delivered in three flights yesterday. The flights were made for a Wellington firm which has 140 cars for the South Island. Ten of the cars are taxis urgently needed in Dunedin. The cars were lifted up and down from the aircraft on fork-lift trucks. Some light trucks may be flown to the South Island next week.—(P.A.)

|

|

|

|

Post by Peter Lewis on Feb 3, 2022 17:53:26 GMT 12

From the CAT Association history:

New Zealand, 1951. An urgent cablegram from Wellington requested at least five C-46s with pilots and a maintenance team immediately — an unusual request because it entailed a Chinese flag carrier operating within New Zealand’s borders; American pilots and Filipino mechanics whose certificates weren’t recognized by New Zealand’s Civil Aviation regulations; adverse tax, labor and currency laws. However this was more than half a century ago when New Zealand residents numbered two million (the country had more sheep than people, the Australians ribbed) and its flexible parliament — more like neighbors than debaters — could change laws with an ease which made victims of bureaucrats envious.

We landed at Wellington’s international airport. The first Kiwi we met, Edgar Gibson, Director of Civil Aviation, greeted us warmly. In WWII he was the Royal New Zealand Air Force liaison to Admiral Bull Halzey. Japan’s aggressive expansion at the beginning of WWII, and England’s weak response made New Zealanders and Aussies edgy. The newly forming Treaty of Australia, New Zealand, USA (ANZUS) happened to pave the way for us. Early 1951 saw the largest strike in the history of New Zealand — 22,000 dock workers, wharfs, and seamen. Edgar Gibson encouraged the creation of a cargo line, Straits Air Freight Express (SAFE). It connected two elongated islands which form the one New Zealand. Up to now, railroad trains stopped at the end of North Island where ferry boats transferred the freight across Cook Straits to South Island’s railroad. We would do the job until newly-made Bristol Air Freighters arrived from England. We called it “Operation Railhead.”

Although Wellington’s modern airport was our North Island terminal, our Southern Island home was Woodburn Aerodrome, a grass field without boundary markers or lights. The New Zealanders wanted us to maximize the utility of our planes by flying at night but lamented the lack of runway lights. “Nothing to it,” I said, and we reverted to coffee cans, rags and oil, which had served us well during night operations in our mainland China days.

Copilot Gene Porter thought of a way of utilizing three C-46s with two captains and copilots. Since the flying time across Cook Straits was only about 30 minutes, the third C-46 would be loaded and waiting for him. The inbound plane was then unloaded and reloaded with cargo in the opposite direction in time for the next inbound pilot to take. The pilots got more flying time in a day’s work, and the planes, a third more utilization. Gene Porter got full credit for his nifty idea.

Dependability and an on-time record endeared us to the Kiwis. Local families insisted on tossing our laundry in with their home washing instead of taking it to a commercial place.

A reporter from the Wellington News interviewed me. It appeared with a headline, “Nothing To It, The Yanks Say,” which showed the astonishing tons of freight we had flown on time without a hitch. When the Mayor of Blenheim made us members of his polished wood private club, I ordered a round of drinks to celebrate the honor. The Mayor replied, “No shouting allowed here,” so I lowered my voice, told the bartender again, and saw bar flies laugh.

The Mayor explained, “Here, in New Zealand, ‘shout’ means you buy someone a drink. Everyone pays his own way here. Many of our members are retired sheep farmers on a low government pension. They shy away from big spenders. But at our club they enjoy an evening with friends while nursing a ten-pence beer. We don’t like big shots who slap a ten-pound note on the bar.”

Sportsmen took us fishing, and Norm Schwartz loved it—he was a good fly fisherman. One of our fishermen friends in a tweed jacket, neck tie, proper wicker basket, told us, “In New Zealand there’s a fish in every stream.” It amused Schwartz but sounded believable to me because I actually caught a trout. Seamen who harpooned whales in Cook Straits invited us to their mother ship to see the action. Blenheim’s Aero Club flew WWII primary single-engine “kites” across the turbulent Straits, appointed us honorary members and threw raucous parties. Lovely, friendly, curious lassies in uniforms of the Royal New Zealand Air Force visited Woodburn Aerodrome.

The only guy who didn’t like New Zealand was our new-hire from CATC although I admired him because Harry Hudson was a self-made renaissance man. Heavy-set, with a walrus mustache and determined expression, he lumbered like a bear.

Hudson hated New Zealand’s dining customs. Sandwiches were English style fingers of crust-less bread with a thin filling. “These peasants don’t know how,” grumbled Hudson while he ran a tabletop production-line of scraping the innards of half a dozen sandwiches into one. He didn’t catch on that a pub resembled a home where you don’t foist demands on your host. New Zealanders were friendly and generous, but a strong sense of personal independence prevailed. When Hud briskly ordered a glass of water, the waitress set it abruptly before him. Pleased with the menu, Hudson said, “I’ll have the roast beef”. But when he added sternly, “a rare cut,” the waitress bristled. He began with soup and asked for a refill. “No seconds,” said the waitress.

“Smith didn’t have soup, I’ll have his.”

“I’ll give you his, down your ruddy neck.”

Hudson clearly needed a boost out of his depression, so I arranged to have him remain overnight at our stopover pub in the larger city of Wellington, on New Zealand’s North Island. The proprietor, appropriately named Scotty, beamed, “I’m so happy to see Yanks again,” and then he told of his life in New York City where he had been a chef for the Vanderbilt’s, the multi-millionaire philanthropists.

“These bloody New Zealanders don’t appreciate my cooking,” he lamented. “I create a gourmet salad and the provincial bods throw out the sliced peppers and onions…I cook bouillabaisse — saffron and all — they take one look at the shells and think it came out of a garbage can. I cook a vegetable crispy and they say it’s raw.” “We have just the man who’ll appreciate your artistry,” I said. “His name is Harry, but we call him Hungry.”

When I described Hudson’s magic at a dinner table, Scotty glowed with excitement. “Oh Lord, it reminds me of the Yank discus thrower in the Olympics, who ate a gallon of ice cream at a sitting.”

“I’ll arrange for our champion to overnight here,” I promised. “You do the rest.”

“Give me time to prepare,” said Scotty. “The rest of you Yanks come with him. I’ll prepare a feast he’ll never forget.” Rubbing his palms with glee, he said, “It brings back my days with the Vanderbilt’s.”

By the appointed evening, every employee in the pub had heard of Hungry Hudson. They placed white linen on the tables; polished silver; water and wine glasses shone. Assistants in the kitchen peeked around the door. Others, off duty, kneeled shoulder-to-shoulder on the ground outside to peer over the ledge of the dining room windows. I felt guilty and nervous. Perhaps I had overstated Hungry Hudson’s prowess.

My fear vanished after watching Hud make the food disappear without shoveling it in. Oysters Rockefeller with Chardonnay; consommé; steamed green beans sliced lengthwise with shreds of almonds; romaine salad, shaved bell peppers, mushrooms, spring onions, olive oil and vinegar dressing with a hint of garlic; strips of tenderloin beef…After the dessert of chocolate mousse and a demitasse of coffee, Hudson dabbed his lips and mustache gently with a linen napkin while Scotty stood over him, overjoyed.

After Scotty disappeared into the kitchen for a moment, Hudson made the statement for which he became famous. We often repeat it as our own.

“I wasn’t really hungry,” Hudson said, “but I didn’t want to hurt Scotty’s feelings.”

|

|

|

|

Post by davidd on Feb 3, 2022 18:53:01 GMT 12

Priceless piece Peter, well found!

|

|

|

|

Post by madmac on Feb 3, 2022 20:13:02 GMT 12

Those DC-3 running freight, both have holes in all the windows, was it just for the sheep or was there another reason?

|

|

|

|

Post by Dave Homewood on Feb 3, 2022 20:24:44 GMT 12

Those holes are gun ports. They are C-47's straight out of RNZAF service. If the C-47 was attacked the troops in the back would be expected to poke their rifles and Bren guns or pistols through the holes and fire back. No bull.

|

|

|

|

Post by madmac on Feb 3, 2022 20:37:13 GMT 12

Those holes are gun ports. They are C-47's straight out of RNZAF service. If the C-47 was attacked the troops in the back would be expected to poke their rifles and Bren guns or pistols through the holes and fire back. No bull. They hadn't shoot at much for at least 6 years. Jokes about shooting wharfies aside, you mean some RNZAF bright spark thought it is was a good way of billing NZR for what would otherwise be dead stock. |

|

|

|

Post by Dave Homewood on Feb 3, 2022 20:38:37 GMT 12

I mean the ports were in the windows from when there was good chance they might be attacked by Japanese fighters in the Pacific.

|

|

|

|

Post by madmac on Feb 3, 2022 20:57:05 GMT 12

Sorry I had just looked a couple of dozen RNZAF Dakota photos and not noticed one dam window hole. But there they are when I looked again.

|

|

|

|

Post by nuuumannn on Feb 4, 2022 11:58:10 GMT 12

This is a cropped version of a picture I took of a C-47 showing the openings up close.  DSC_0613 DSC_0613 The aircraft is at the Ste Mère-Église Airborne Museum. |

|

|

|

Post by madmac on Feb 4, 2022 12:35:31 GMT 12

This is a cropped version of a picture I took of a C-47 showing the openings up close.  DSC_0613 DSC_0613 The aircraft is at the Ste Mère-Église Airborne Museum. With the blanks in, which the RNZAF seemed to be in short supply or just gave up on after the rubber got a bit hard and they kept falling out (didn't see any in the post war photos). There is apparently two types of window holes, the 2nd I guess for machine guns. a couple of cropped pictures from the Airforce Museum collection

|

|

|

|

Post by nuuumannn on Feb 4, 2022 12:53:55 GMT 12

With the blanks in, which the RNZAF seemed to be in short supply or just gave up on after the rubber got a bit hard and they kept falling out (didn't see any in the post war photos). There is apparently two types of window holes, the 2nd I guess for machine guns. The type shown in my image were simply vents to allow air into the aircraft. Note the absence of the moveable grommet. |

|

|

|

Post by tbf2504 on Feb 4, 2022 13:41:05 GMT 12

In my book DC3 Southern Skies Pioneer there is a story from Laurie Bade (of one and a half wing C47 fame) that he arrived at his C47 for a flight from Whenuapai to the SWPA and found a .303 machine gun

in a box on the floor. When asked what it was for he was informed to defend yourselves should you be attacked. Laurie made the immediate command decision not to carry the gun as there was more danger

from his enthusiastic crew/gunners hitting their own airframe than any perceived threat from roaming Japanese fighters

|

|

|

|

Post by Deleted on Feb 4, 2022 13:57:46 GMT 12

If you research all the Eric Lee-Johnson photo archives you will see another normal photo of that Fletcher and reference to the rego and pilot. Thanks for the heads-up oj, and for your reminiscences  |

|

|

|

Post by madmac on Feb 5, 2022 15:38:17 GMT 12

|

|

|

|

Post by Deleted on Feb 5, 2022 18:54:26 GMT 12

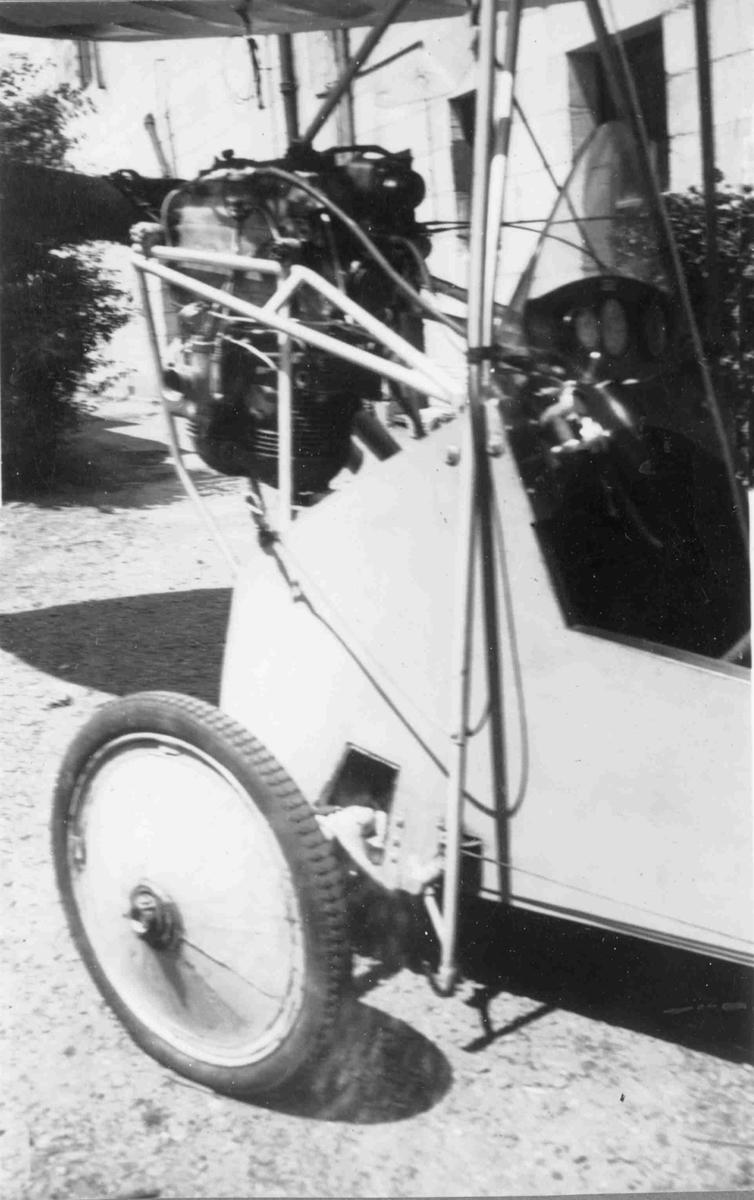

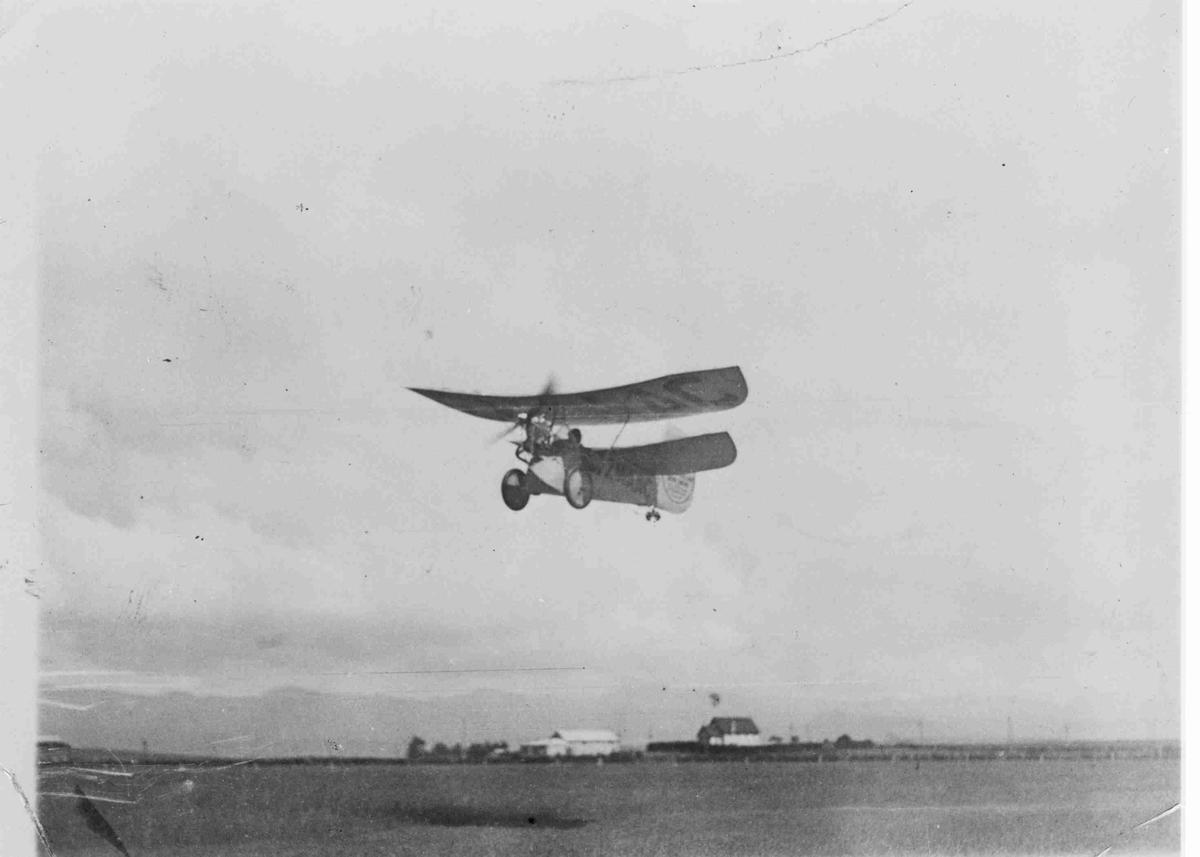

Found a good set of photos of the flying Flea ZK-AAC. All photos Collection of the Waitaki Archive Fantastic, well done Duncan and thanks for sharing! That's an awesome photo. |

|

|

|

Post by davidd on Feb 5, 2022 19:18:00 GMT 12

Not certain that W L Notman ever got to fly this aircraft, but I could be wrong. I met him many years ago (cannot remember how or why or where!) and he did give me a few of his remaining photographically reproduced advertising cards, including one for the Scott Squirrel engine (2 stroke, 2-cylinder inverted). However he persuaded (probably by financial inducement!) a qualified pilot to test fly it for him, which he did. Unfortunately the aerodrome they used for the test flight was not registered at the time, and the authorities noted that this class of aircraft (which had a rather chequered career by this stage) could only be flown in New Zealand within a restricted area within so many miles of a registered aerodrome, so the test flight was considered to be in breach of the law. The pilot (and possibly also Notman) ended up in court and had to cough up several pounds each for their failure to understand these regulations - it was all in the papers! The tribulations of being a pioneer aviator.

|

|

|

|

Post by madmac on Feb 5, 2022 20:52:04 GMT 12

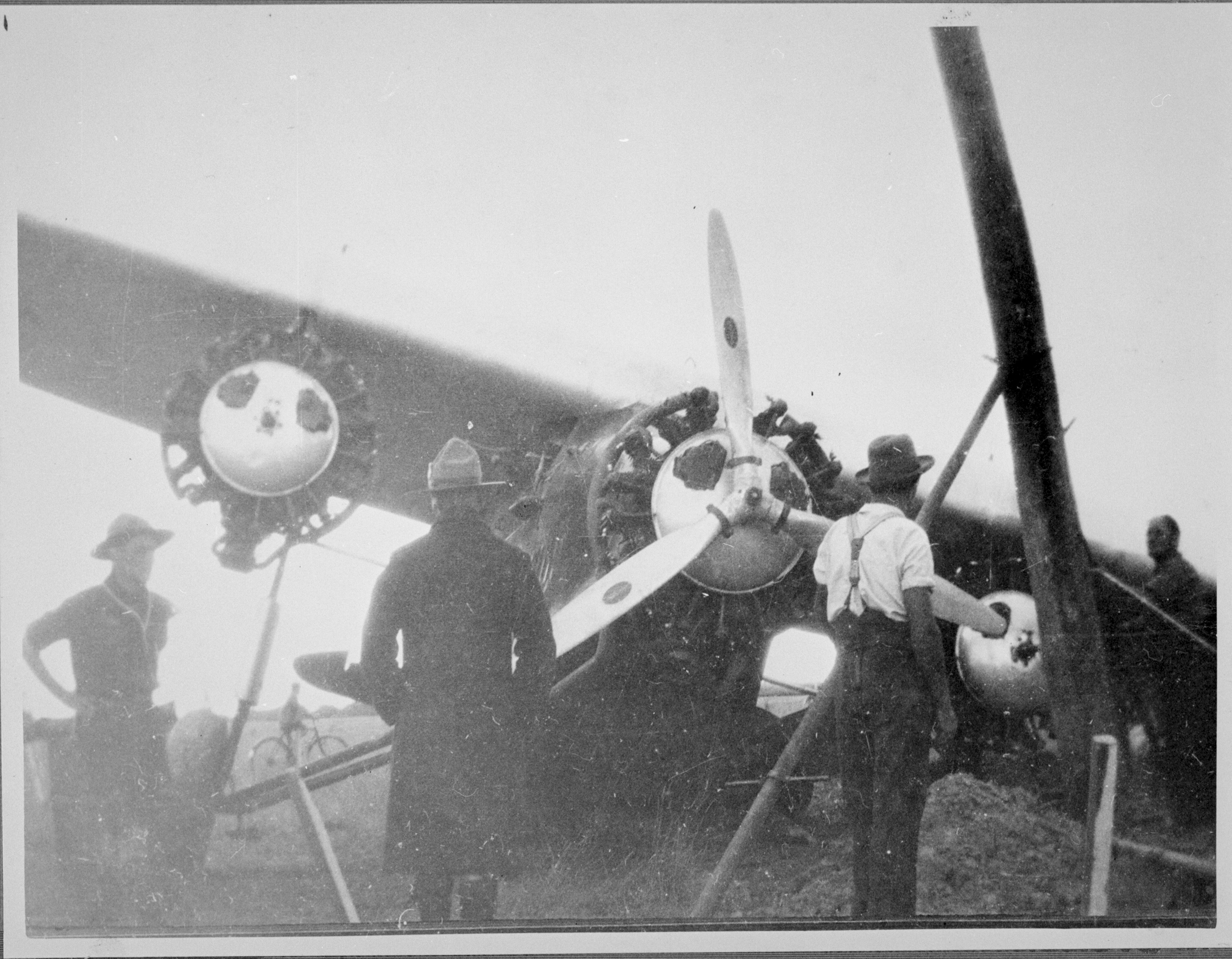

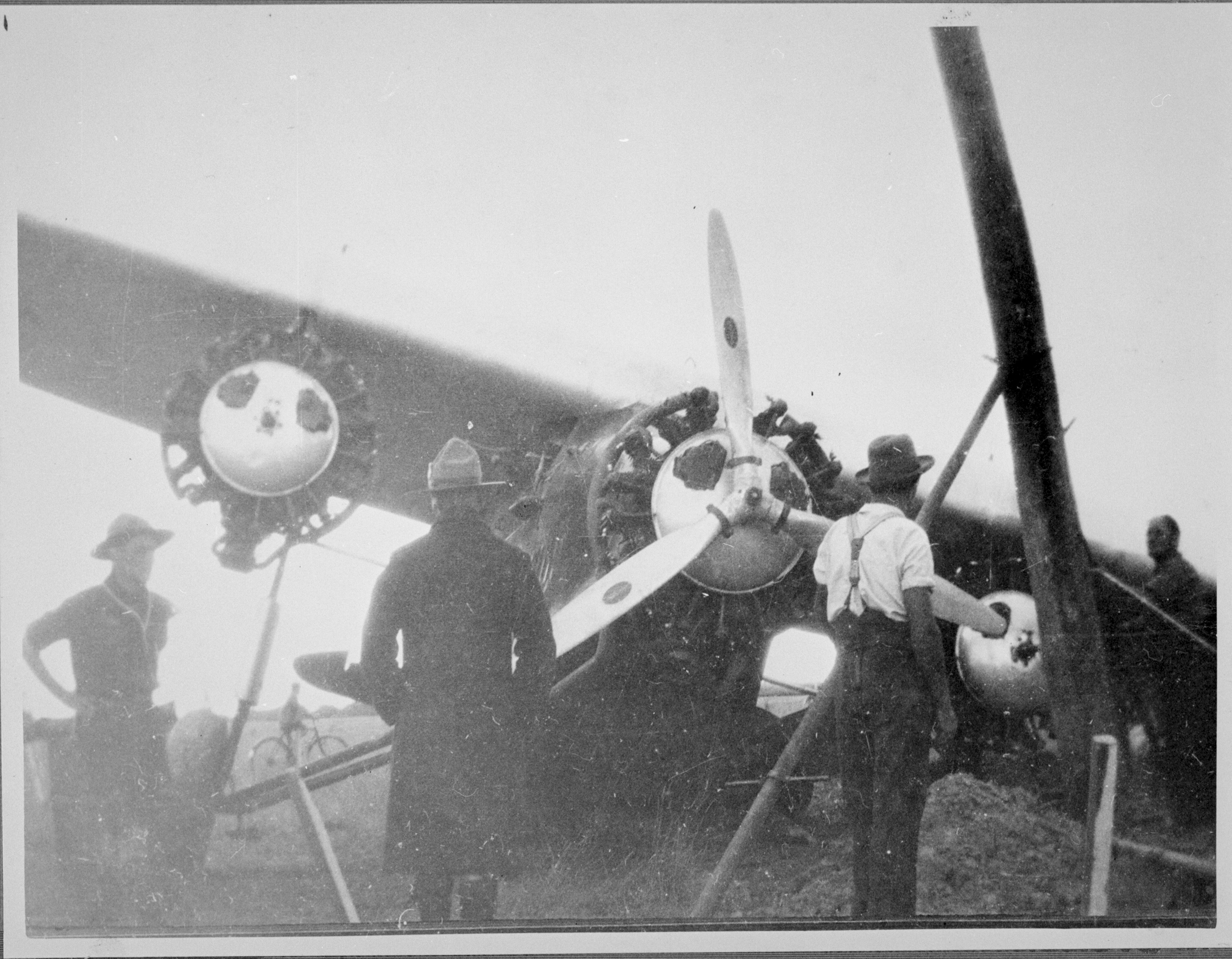

I came a cross a number of photos of the recovery and repair of the Southern Cross & thought there must be a few more interesting pictures, so here we go. R.N. Boulton filtering fuel into Southern Cross, VH-USU, prior to New Zealand flight, 1933 [picture] / Sydney Morning Herald and Sydney Mail, Sydney National Library of Australia

Men hauling Southern Cross, VH-USU, back from tide prior to Australia-New Zealand flight, Gerringong Beach, 1933 [picture] / Sydney Morning Herald and Sydney Mail, Sydney National Library of Australia

""Southern Cross" at Alma airport, Totara. "Plume" fuel truck. Aircraft was the first to fly the Tasman Sea in 1928. Made a refuelling stop at Totara Airfield on March 5th 1933, during a tour of New Zealand after the crossing." culture waitaki  "Crowd alongside the Southern Cross aeroplane at Wellington Airport, Rongotai, 1933. Photograph taken by Sydney Charles Smith." National Library  "Airplane 'Southern Cross' refuelling, circa 1931, New Zealand, by Leslie Adkin." Te Papa

"Shows the Fokker tri-motor 'Southern Cross' of Charles Kingsford Smith in a hangar, probably at Martinborough. A Bristol Fighter of the N.Z. Permanent Air Force is at left." Masteron District Council Archives

"Charles Ulm's monoplane 'Faith in Australia' at the Auckland Aero Club's Māngere airfield. Ulm, who had been Kingsford-Smith's co-pilot on the Southern Cross in 1928, crossed the Tasman again in his own plane, the Avro X 'Faith of Australia', on 3 December 1933. With him on the flight were co-pilot and wireless operator G.U. Allen, engineer R.T. Bolton, Ulm's wife and his secretary Miss N. Rogers. Mrs Ulm and Miss Rogers were thus the first women to cross the Tasman by air. Ulm landed at New Plymouth and proceeded to Auckland on 9 December 1933." Auckland Libraries

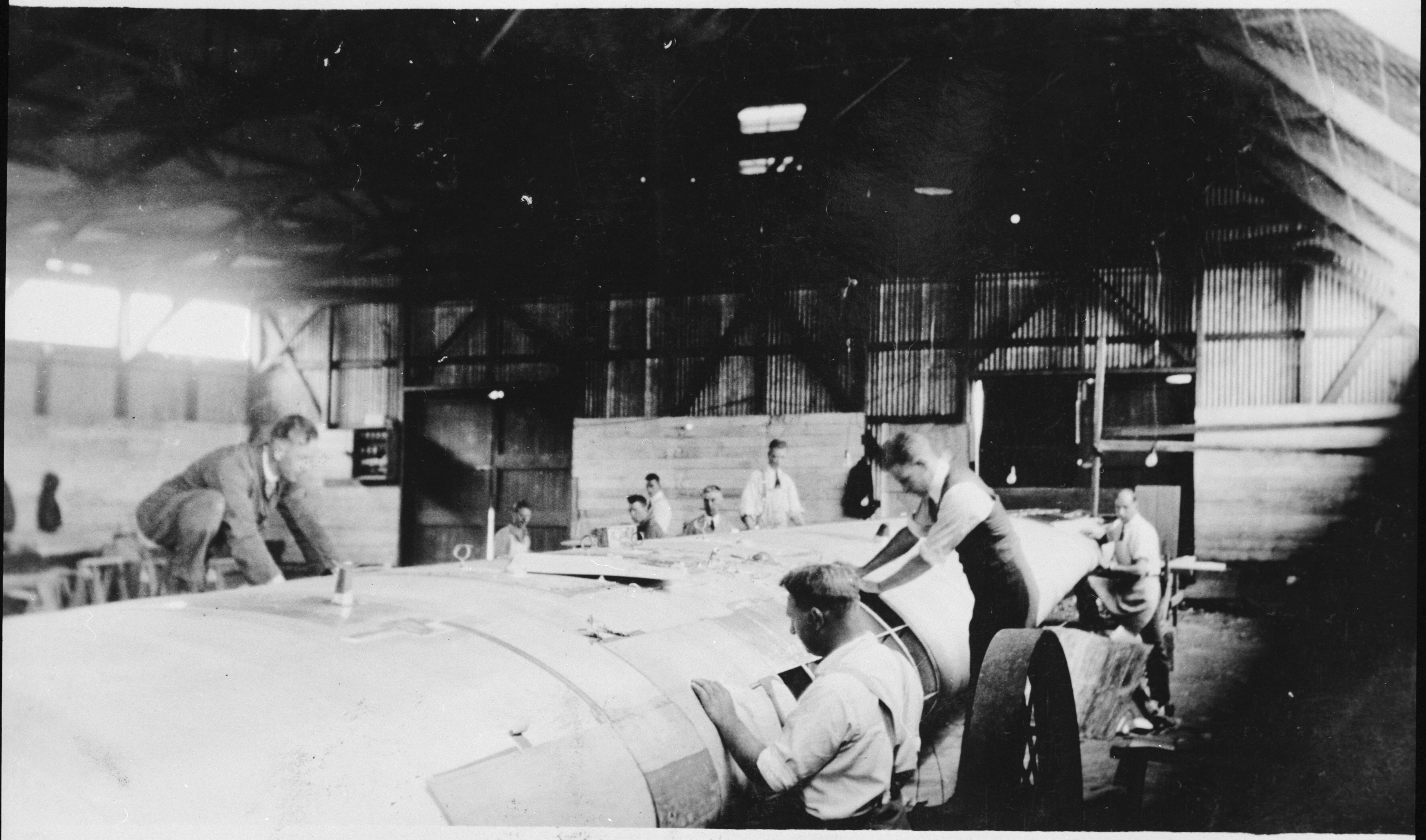

"Taken from the supplement to the Auckland Weekly News 8 February 1933 p035" Auckland Libraries  The next 4 photos are Manawatu Heritage. "This photograph shows the damaged "Southern Cross" when it landed at Milson Airport, Palmerston North. Sir Charles Kingsford Smith and crew of the 'Southern Cross', a Fokker F. VII Trimotor aircraft, were delayed in Palmerston North for several weeks after the aeroplane's wing was damaged during taxiing 4 February 1933. The left wing sank axle-deep in a boggy patch of ground. The left wing and port propellor were damaged, taking several weeks to be repaired. Kingsford-Smith left for Sydney a few days later in the "Makura" for a much needed holiday." Manawatu Heritage

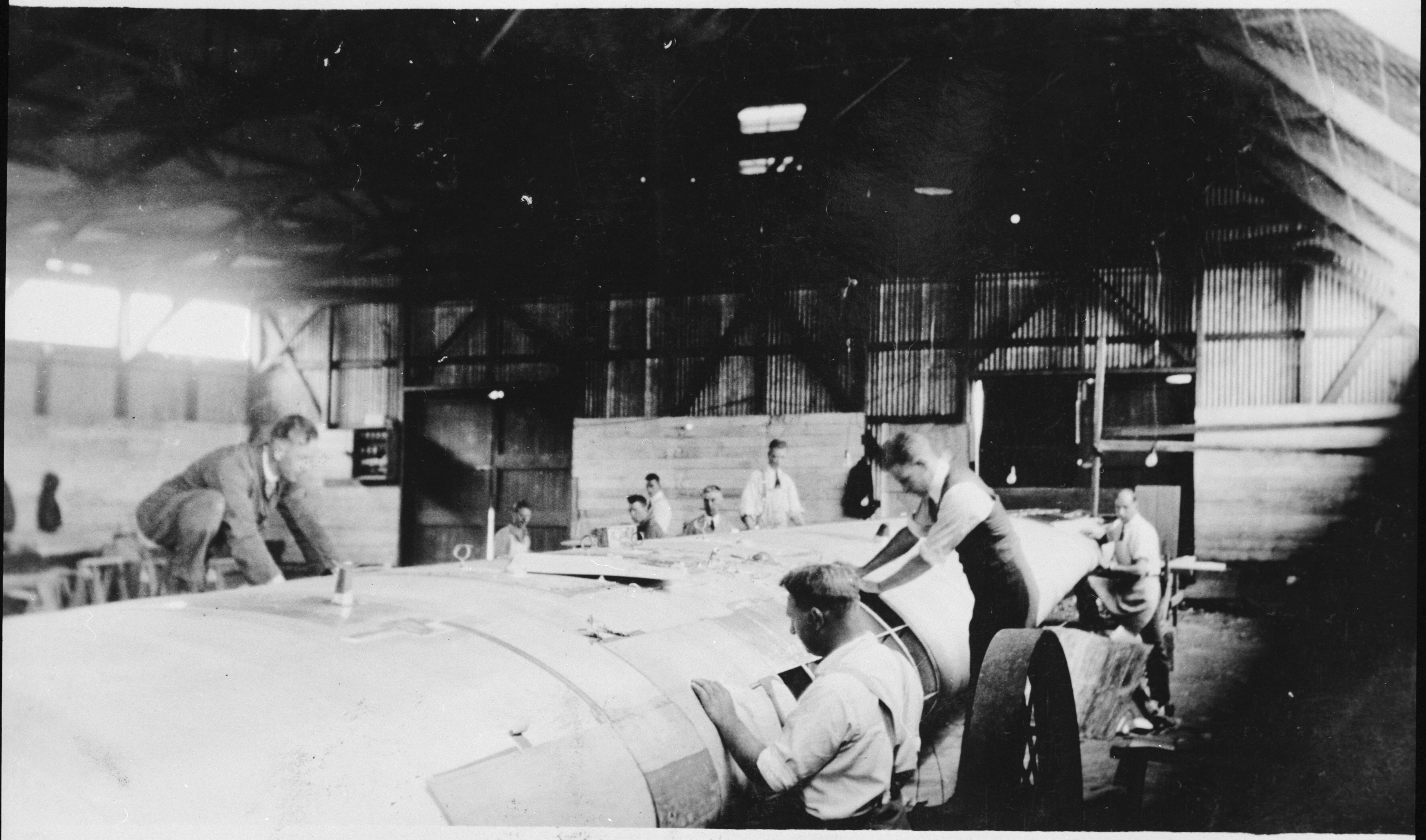

The next 4 are MOTAT     The next 2 are Manawatu Heritage "Repairing the wing of Kingsford Smith's "Southern Cross" aircaft with 3-ply wood in a Palmerston North Agricultural and Pastoral showground building in Waldegrave Street. Sir Charles Kingsford Smith and crew of the 'Southern Cross', a Fokker F. VII Trimotor aircraft, were delayed in Palmerston North for several weeks after the aeroplane's wing was damaged during taxiing at Milson Aerodrome 4 February 1933."

|

|