|

|

Post by flycookie on Dec 12, 2007 15:41:19 GMT 12

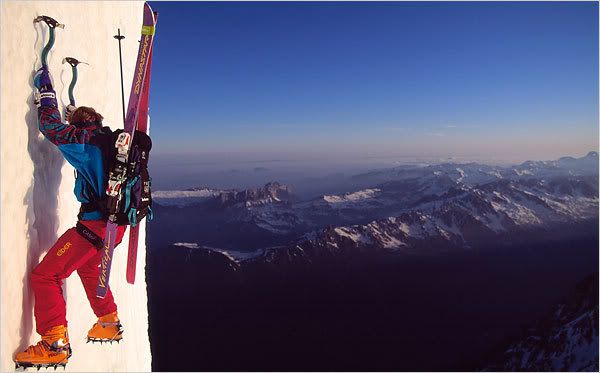

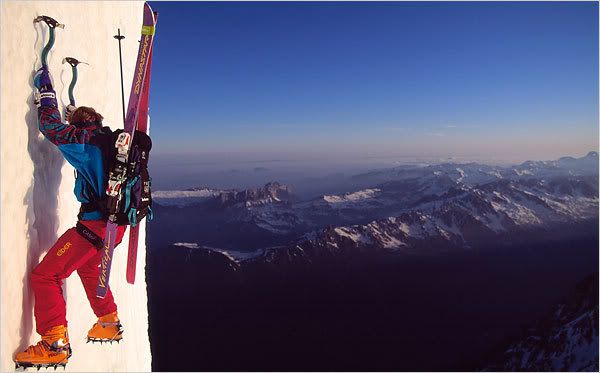

www.nytimes.com/2007/12/10/sports/othersports/10flying.html?_r=1&oref=slogin Caprion: Jeb Corliss, left, wearing his wing suit. Right, skydivers with wing suits flying over the Florida Keys before releasing their parachutes. December 10, 2007 Flying Humans, Hoping to Land With No Chute By MATT HIGGINS Jeb Corliss wants to fly — not the way the Wright brothers wanted to fly, but the way we do in our dreams. He wants to jump from a helicopter and land without using a parachute. And his dream, strange as it sounds, is not unique. Around the globe, Mr. Corliss said, at least a half-dozen groups — in France, South Africa, New Zealand, Russia and the United States — have the same goal in mind. Although nobody is waving a flag, the quest has evoked the spirit of nations' pursuits of Everest and the North and South Poles. "All of this is technically possible," said Jean Potvin, a physics professor at Saint Louis University and a skydiver who does parachute research for the Army. But he acknowledged a problem: "The thing I'm not sure of is your margins in terms of safety, or likelihood to crash." Loïc Jean-Albert of France, better known as Flying Dude in a popular YouTube video, put it more bluntly: "You might do it well one time and try another time and crash and die." The landing, as one might expect, poses the biggest challenge, and each group has a different approach. Most will speak in only the vaguest terms out of fear that someone will steal their plans. Mr. Corliss will wear nothing more than a wing suit, an invention that, aeronautically speaking, is more flying squirrel than bird or plane. He plans to land on a specially designed runway of his own design. It will borrow from the principles of Nordic ski jumping and will cost about $2 million, which explains why he is so much more vocal than the others about his quest. Mr. Jean-Albert figures he could glide to a stop on a snowy mountainside. "The basic idea is getting parallel to the snow so we don't have a vertical speed at all, there is no shock, and then slide," he said. Then there is Maria von Egidy, a wing suit maker from South Africa, who said she had begun creating a suit that would allow pilots to land on their feet on a horizontal surface. "I think people will recognize this makes sense," said Ms. von Egidy, who has been pursuing financing for her suit. "Why didn't someone think of this long ago? I'm hoping that will be the reaction." That depends on whom you talk to — the endeavor is either quixotic or brave. Even Evel Knievel had the sense to pack a parachute when he climbed into his Skycycle X-2 to jump Snake River Canyon in 1974. This spring, Mr. Corliss will attempt the first of three tests to prepare for his goal. Wearing his wing suit, he will jump from a plane, which will then execute a 270-degree turn and descend at a steep angle. He will fly down to the plane and re-enter it. This will be his second attempt at the benchmark. His first failed when he missed the plane; he deployed his parachute and glided to earth. "The plane was flying too fast," said Mr. Corliss, who gained a degree of notoriety in April 2006 when the police arrested him after he was stopped from jumping off the Empire State Building's observation deck. A judge dismissed the charges. Wing suits are not new; they have captured the imagination of storytellers since man dreamed of flying. From Icarus to Wile E. Coyote, who crashed into a mesa on his attempt, the results have usually been disastrous. But the suits' practical use began to take hold in the early 1990s, when a modern version created by Patrick de Gayardon improved safety. Modern suit design features tightly woven nylon sewn between the legs and between the arms and torso, creating wings that fill with air and create lift, allowing for forward motion and aerial maneuvers while slowing descent. As the suits, which cost about $1,000, have become more sophisticated, so have the pilots. The best fliers, and there are not many, can trace the horizontal contours of cliffs, ridges and mountainsides. "Wing-suit flying totally changes the way you fly and you jump," said Mr. Jean-Albert, who is seen in his YouTube video skimming six feet above skiers in the Swiss Alps. "It creates a third dimension because in normal skydiving your trajectories are pretty vertical." Some wing suit pilots have briefly slowed the vertical descent to about 30 miles an hour. But they are moving forward horizontally at 75 m.p.h. Even if a pilot could achieve such speeds, Mr. Potvin said, any slight wrong movement could cause a crash and certain death. Mr. Corliss said he could land safely at about 120 m.p.h. To protect his neck, he said, he will attach his helmet to a rigid-framed exoskeleton with the wing suit. "Is there some crazy person out there who might beat me because he's willing to do something more dangerous than me?" Mr. Corliss, 31, said by telephone from his home in Malibu, Calif. "Yes, but I'm not that guy." Mr. Corliss has plenty of experience jumping from high places. A BASE jumper — someone who leaps from buildings and cliffs and lands with a parachute — he has made more than 1,000 jumps, including from the Eiffel Tower and the Golden Gate Bridge. He was encouraged by the response to his plans from Vertigo, an aerospace company in Lake Elsinore, Calif., that has worked on projects for NASA and the United States military. "Is it possible?" said Roy Haggard, a founder of Vertigo and a skydiver himself. "Yeah." Mr. Haggard had a plan similar to Mr. Corliss's, but he said he had neither the time nor the money to pursue it. If Mr. Corliss can raise enough money, Mr. Haggard's company will help him design and build the runway. "Everybody wants to be the first one to do it," Mr. Haggard said. Which leads to an obvious and inevitable question: Why? "Because everybody thinks that it's not possible," Mr. Corliss said. "The point is to show people anything can be done. If you want to do amazing things, then you have to take amazing risks." Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company

|

|

|

|

Post by FlyNavy on Dec 12, 2007 17:01:29 GMT 12

MEEP MEEP (as in Road Runner cartoon) BLEEP BLEEP. "If you want to do amazing things, then you have to take amazing risks." Yeah right.  |

|

|

|

Post by flycookie on Dec 19, 2007 15:45:41 GMT 12

I think this looks safer and more likely to yield success than the amazing risk takers described in the Times story.  |

|

|

|

Post by FlyNavy on Dec 19, 2007 16:24:10 GMT 12

This kind of thing will be safer on the moon. Gravity sucketh less there.  |

|

|

|

Post by flycookie on Dec 22, 2007 16:58:35 GMT 12

ONLY IN NORWAY(now there's a sentence you're unlikely to ever see again)   www.economist.com/displaystory.cfm?story_id=10278696&CFID=4664663&CFTOKEN=57f6d9179587a825-00326843-B27C-BB00-012751FA37E571B5 www.economist.com/displaystory.cfm?story_id=10278696&CFID=4664663&CFTOKEN=57f6d9179587a825-00326843-B27C-BB00-012751FA37E571B5Human lemmings Dec 19th 2007 For those who like leaping into the abyss, Norway is the place to do it TRY this next time you are strolling on a cliff. Toss a rock (the size of a blood orange is good) over the edge and begin to count. It falls at the speed of a tumbling human so will reach 200km per hour after nine seconds, roughly the acceleration of a supercar. Keep counting. If the cliff is sheer and tall, like the more dramatic ones above a Norwegian fjord, you should be able to tick off many seconds before hearing a distant crack. That is how long you might fly, unaided, before your soft flesh is mangled on the granite below. Next, get ready to hop off. You will probably be terrified, which is a shame, for fear interferes with perception. Tunnel vision blocks the smell of moss on the cliffside, the tinkling of a waterfall halfway down. But the adrenalin rush, legs hollow and wobbly, ensures it is a memorable experience. “That second before you step off is the best. Everything is quiet, you step into emptiness,” says Karina Hollekim who, after more than 400 flying leaps, is emerging as a star of increasingly popular films about falling off high objects. Now go over. A Superman pose (keep your stomach in) is the standard method, some 45° forward, so that in the first five or six seconds you become horizontal. The more daring go head first to get up speed. At first you hardly feel the motion. There is no sound (screams aside); not even the rustling of wind in your clothes. You may feel you are hanging, frozen, in mid-air. “When I first jumped it seemed I wouldn't move, or fly, at all. For those first seconds I thought it was not working,” recalls Stein Edvardsen, a pioneering Norwegian jumper who has been at it for more than a decade. “It felt like an eternity as Mother Earth was pulling me down,” he says. Butterflies are unlikely—it is not like hitting turbulence in a plane—because your stomach falls at the same speed as the rest of you, but you feel weightless and time slows. Then, after six seconds, there is friction. “To get an idea of what it feels like, put your hand out of the window of the car when you are driving at 150km per hour,” suggests Mr Edvardsen. So far you have been falling; now you are ready to fly. Being close to the wall makes it especially satisfying. Ms Hollekim likes spotting startled birds that nest in cracks in the rock or, jumping from skyscrapers, to study roofs of smaller buildings as they rise up. At this speed the human body may curve away from the cliff. At a popular spot in Norway, Kjerag near Stavanger in the west, you have 16 seconds of freefall in which to swoop around, some of it just ten metres from the rock face. In Trollveggen (Troll Wall), an even more dramatic drop in the middle of the country, you may plummet for a long half minute, allowing time for backflips, somersaults, or hurtling side by side with a friend. Then, sometimes as late as a second or two before impact, you should find the cord to deploy your parachute. You need both time and speed for the chute to prove useful, however. Pulling the cord too late is one of the easier ways to kill yourself. Falling too slowly—if you have made the mistake of leaping from something near the ground, like a church tower—could be fatal, too, as the parachute may fail to open fully. To prolong the flight some have turned to fancy dress. Wingsuits, which have flaps between the limbs, look ridiculous but allow cliff-jumpers to float in the air for minutes at a time, changing direction at will. Oyvind Lokerberg in Trondheim is one of a group of ten local men who test the dynamics of flying from mountains in wingsuits. The goal is to get up as much speed as possible, giving the flyer more control. “Today you can reach 350km per hour in almost a head-on dive, then when you pull up into the horizontal you can be moving at about 230km per hour,” he says. The perfect suit covers the smallest area possible while still giving decent lift (the worst are about as effective as clinging to a mattress). The current fashion seems to be a suit that looks like a bat or a flying fox (see left). Mr Lokerberg and his colleagues refine their designs in wind tunnels then try them out on mountains. Eventually, thinks Ms Hollekim, someone will try to land in a wingsuit, without using a parachute. Mr Lokerberg, laughing, is sceptical: “Remember one day Newton [or rather his law of gravity] is going to come and get you.” A flight in a wingsuit alone would demand an extremely soft spot—a hillside covered in deep powdered snow, for instance—to land in. Until then enthusiasts seek new thrills by finding new places to fall from—“You get tired of jumping off the same cliff every day,” says Mr Edvardsen—or by trying more convoluted acrobatics on the way down. Ms Hollekim grew fond of throwing herself off mountains while on skis. The weight of the equipment makes it much harder to keep upright in the air and skis stop you looking over the edge before you leap. Now, after 25 efforts, she thinks ski-basing is a bit too risky. Gripping videos on YouTube show others sledging off mountain tops, cartwheeling over the edge and dancing their way into the abyss. This weird sport is known as base-jumping: the name refers to the four things that can be leapt from—buildings, antennae, spans (bridges) and earth (cliffs). It is increasingly popular. In America enthusiasts make an annual pilgrimage to El Capitan, a cliff in Yosemite National Park which was the site of the first such jump, in 1966. Those keen on leaping from tall buildings flock to cities in Asia. Kuala Lumpur hosts an annual world championship. But Norway, well-supplied with fjords and cliffs, remains the sport's spiritual home. Carl Boenish, the American who named it, died jumping off Trollveggen in 1984; Thor Axel Kappfjell (pictured top), another base-jumping hero, died jumping off Kjerag in 1999. Norwegians are an outdoors sort of people, and all that nature “invites you to use it” says Ms Hollekim. Jumpers are supposed to be experienced sky-divers before leaping from land. In practice not everyone is. The kit (an appropriate parachute and a good pair of boots) is about $2,500 new, and some jumpers cut costs by buying second-hand. Malfunctions are often deadly. As there is no time to deploy a second parachute nobody carries a spare. Organised events seem pretty safe: this summer at Kjerag, for example, saw 2,500 jumps completed with only a broken ankle to show for it. But fatal accidents are hardly uncommon. Jumping off Trollveggen was banned after 11 accidents and four deaths in the space of 280 jumps in the early 1980s. An experienced Australian was killed in August in north-west Norway when his parachute failed. A list online details 120 jumpers killed at the latest count. The cause of death is usually described as “impact”, although drowning has claimed a few lives. Parachutes open too late or squalls of wind send a jumper into a cliff. The unluckiest crash onto a ledge and die slowly from exposure. But without the risk, it wouldn't be fun. Despite appearances it does not seem to attract the mad or suicidal. Jumpers have to be meticulous about their gear, and many seem as attracted by the outdoor life as by the adrenalin. The enthusiastic Ms Hollekim is thrilled to be alive and walking. She limps off to her latest movie premiere in London after describing how an entangled parachute nearly killed her in 2006. She hit rocks at more than 100km per hour. Her legs were pulped, fractured in 25 places, and she lost 3.5 litres of blood. She spent four months in hospital, underwent 15 operations, narrowly avoided amputation, and endured nine months in rehabilitation. The pain, she says, was unbelievable. But jumping off cliffs has been the most powerful experience of her life and she regrets none of it. “It forces you to feel. Extreme fear, then relief, then happiness. In my everyday life I don't feel that much. But, in the air, it's like being in love.”

|

|

|

|

Post by FlyNavy on Dec 22, 2007 18:39:49 GMT 12

Nor Way or the Fly Way? ;D Batty people (even those in Wing Suits [with Bat Wing Collars?] have difficulty explaining themselves. Read the last para above to see what I mean.  Perhaps English (and sanity) are a second language.  |

|

|

|

Post by flyjoe180 on Dec 22, 2007 22:40:36 GMT 12

Wow, talk about extreme! I think you might be onto something there Navaliator  |

|

|

|

Post by kiwi on Dec 23, 2007 11:00:17 GMT 12

My young fella sent me a picture of a couple of his mates doing this in Aussie the other day . He is a skydiver , has a wing suit and I can see one day he will base jump as he has always been an adrenalin junkie .

|

|

|

|

Post by flycookie on Dec 23, 2007 12:55:53 GMT 12

movies.nytimes.com/2007/12/21/movies/21stee.html?ref=movies movies.nytimes.com/2007/12/21/movies/21stee.html?ref=moviesDecember 21, 2007 Talk About Slippery Slopes By STEPHEN HOLDEN One of the daredevils in “Steep,” a documentary about extreme skiing, insists he is not hooked on the adrenaline rush of this death-defying sport. His denial is hard to believe. In one scene after another of this movie, written and directed by Mark Obenhaus, skiers hurtle down slopes at angles of 55 degrees or greater and leap off precipices into the unknown. The tiniest miscalculation, we are repeatedly told, could result in death. The sport’s practitioners — addicts might be a better word — would rather talk about how extreme skiing puts them totally in the moment and gives them an appreciation of life so acute it makes this sport, which has a high fatality rate, worth pursuing at all costs. There is a lot of mystical mumbo jumbo about how mountains are living, breathing things whose moods must be gauged before you venture onto their slopes; on a bad day a grouchy mountain can bite back. Behind it all is the same competitive spirit that disciples of religious cults dish out to the uninitiated. The proselytizer fervently believes that he or she (but usually he) has a richer life than his unenlightened audience. That may be why “Steep” so often sounds like a promotional film. The movie, photographed in high-definition video by Erich Roland, is an undeniably impressive visual spectacle that follows the sport from Wyoming to France, British Columbia, Iceland and Alaska. Like that of its sister sport, surfing, extreme skiing has a history of one feat topping another as techniques are developed and challenges devised. The worldwide search for the highest wave is paralleled by the search for the steepest, wildest, most dangerous slopes and for perfect snow. Perfection is to be found, according to the movie, in the extreme-skiing mecca of Valdez, Alaska, where the white stuff has the texture of velvet. “Steep” arbitrarily begins its history with a lone descent of Bill Briggs in 1971 on Grand Teton mountain in Wyoming. His accomplishment, witnessed by no one but attested to by aerial photographs of his ski tracks, was all the more remarkable because he was born without a hip joint, and multiple surgeries had left him with a limp. Since then a widening search for adventure has sparked the popularity of what is called big mountain skiing, two of whose hubs, visited by the movie, are Chamonix, in the French Alps, and Valdez. The sport’s popularity has been spread by video, with Greg Stump’s 1988 film, “The Blizzard of Aahhh’s,” cited as a seminal work. We meet the sport’s macho clown, Glen Plake, a wild man with a two-foot high Mohawk, and its composed, apparently fearless female virtuoso, Ingrid Backstrom. Pushing the limits of extreme skiing is Shane McConkey, who has pioneered ski basing: skiing off a cliff at full speed carrying a parachute. The most consistent presence in the film is Doug Coombs, who in 1991 won the first World Extreme Ski Championship in Valdez. With his wife, Emily, he founded Valdez Heli-Ski Guides, which made the Chugach Range in Alaska a magnet for skiers, who are dropped off by helicopter on mountain peaks from which they descend at lightning speeds. In the film Mr. Coombs, who died while skiing with friends on April 3, 2006, reflects on the risks of his sport and sounds resigned to his luck eventually running out. To the detached observer the line between this cheerful fatalism and flirting with suicide seems imperceptible. STEEP Opens nationwide on Friday. |

|

|

|

Post by FlyNavy on Dec 23, 2007 20:55:14 GMT 12

Why in these stories is the punchline in the last paragraph. Put the closer in the first paragraph and we can stop reading then and there: "In the film Mr. Coombs, who died while skiing with friends on April 3, 2006, reflects on the risks of his sport and sounds resigned to his luck eventually running out. To the detached observer the line between this cheerful fatalism and flirting with suicide seems imperceptible." BoomBoom. Sadly.

|

|

|

|

Post by flycookie on Jan 5, 2008 15:38:40 GMT 12

www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=/news/2007/12/28/wskydive228.xmlSkydiver to attempt to 'fly' unaided By Catherine Elsworth in Los Angeles Last Updated: 11:52pm GMT 31/12/2007 A skydiver is aiming to achieve what was long presumed impossible - flying thousands of feet through the air without a hang glider or parachute and landing safely on the ground. Jeb Corliss, 31, is convinced he can become the first person to achieve unaided human flight when he jumps out of a helicopter or plane at least 2,000 feet above Las Vegas wearing only a special wing suit. The daredevil, a professional base jumper who was last year arrested for trying to leap off the Empire State Building, he is just one of a number of people around the world racing to accomplish the feat. Teams in France, South Africa, New Zealand and Russia are also working on projects they say will enable them to "fly". But after a breakthrough earlier this year, Corliss, who has been focused on his attempt for the past seven years, is confident it is within his grasp. "We're close. Obviously we need to keep some things a bit secret so one of these other groups doesn't take my ideas and potentially beat me. But it's definitely possible and can be done safely." He has spent more than a decade performing more than 1,000 jumps from planes, bridges, cliff faces, skyscrapers and landmarks across the world and has been practising "flying" in wing suits for nine years. The outfit, which has a metal exoskeleton and nylon fabric between the legs and under the arms, "changes the shape of your body", said Corliss, a former host of the Discovery Channel show Stunt Junkies. He likens the effect to that of a flying squirrel. "I can get very close to objects and move away from them. I could fly through an open window," he said. "Recently I flew under the arm of the statue of Christ the Redeemer in Rio De Janeiro. I came within 5 ft of the statue and 6 ft of people's heads and I did it six times in a row on the exact same flight path. In a wing suit I can basically fly exactly where I want." Although the attempt has been dismissed by some as "sheer madness", Corliss said safety was his number one priority and he would always ensure he was able to abort the landing and open a parachute if it felt unsafe. Debate is rife amongst Corliss and his rivals as to the best way to land. One rival, Loïc Jean-Albert of France, had said he believes he could glide to a stop on a snowy slope. Corliss, who lives in Malibu, hopes to raise 2 million dollars to build a special runway with the help of an aerospace firm. Video clip of Jeb Corliss on Youtube here:

|

|

|

|

Post by flycookie on Jan 14, 2008 16:15:22 GMT 12

stuff.co.nz/4355911a1861.htmlMonday, 14 January 2008200801140500 Risk-taking instinctive People drawn to high-risk adventure sports can blame inherited personality traits – and may have cause to be grateful that the same instincts don't draw them into more anti-social pursuits. Adventure sports such as mountaineering, kayaking, rock climbing, mountain biking and base jumping are increasingly popular. These risk-taking sports court significant dangers and attract individuals who are prepared to gamble their personal safety, and at times their life, in search of a rush of excitement or an unusual accomplishment. Paradoxically these sports have increased in popularity at a time when modern societies have become obsessed with risk-avoidance and risk- management. Could it be that the bombardment of ACC warning signs highlighting the risks of everything from falling off a curb to wandering cattle, the current culture of blame, hand rails, safety bars and compulsory helmet use have contributed to this trend? There is growing evidence to suggest that the propensity to take risks is strongly determined by the chemistry of the brain – "hard-wired". Risk-taking genes and exploratory behaviours are likely to have conferred specific advantages in the early (hunter and gatherer) stages of human evolution, and therefore may have become more common through natural selection. Despite the changed social environments these primitive instincts continue to exert a strong influence, and the modern civilisations that pride themselves on risk-avoidance and predictability may indeed be the recruiting ground of adventure sports people. Risk- taking or "extreme" sports may well provide socially sanctioned opportunities for the expression of risk-taking instincts. As a mountaineer and psychiatrist, I have been involved in a number of studies to try to determine whether people who take up adventure sports have unique personalities, and whether biological and genetic factors contribute to their choice of leisure activity. Also, as New Zealand currently promotes itself as an adventure destination, where "extreme" sports and activities are popular and traded commercially, it is important to determine just how dangerous these sports are. In a New Zealand-based study of experienced and committed mountaineers, I found that almost half of them had suffered at least one climbing related injury. Two-thirds of those injured were hospitalised and 20 per cent required more than three months to recover, or were left with long-term health problems. Four years after starting the study there was a 10 per cent death rate (five deaths) – four due to climbing accidents. Other studies of mountaineers have found similar results. For example, Murray Malcolm from the University of Otago found that the death rate from climbing in the Mount Cook National Park was 5000 times greater than from work-related injuries. The death rates from climbing on the highest peaks in the park were similar to those of climbers to peaks over 7000m, approximately 4 per cent. I also found that the personality of climbers was quite different to that of average people. Climbers scored higher in the areas of novelty-seeking and self- directedness and lower on harm-avoidance. What this suggests is that climbers generally enjoy exploring unfamiliar places and situations. They are easily bored, try to avoid monotony and so tend to be quick- tempered, excitable and impulsive. They enjoy new experiences and seek out thrills and adventures, even if other people think that they are a waste of time. When confronted with uncertainty and risk, climbers tend to be confident and relaxed. Difficult situations are often seen by climbers as a challenge or an opportunity. They are less responsive to danger and this can lead to foolhardy optimism. Climbers also have good self-esteem and self-reliance and therefore tend to be high-achievers. Base jumping is probably the most dangerous sport in the world and involves parachute jumping from either tall natural features or man- made structures. The parachute is initially closed and is opened after a (short) free fall. In a study of base jumpers, I also found a high rate of injury– two-thirds of the participants had suffered at least one base jumping accident. Almost all of those injured required hospital treatment and two-thirds needed more than three months to recover, or were left with long-term health problems. All base jumpers estimated that they had had "near- misses" and all of them had witnessed friends die from the sport. Overall, the personalities of base jumpers were very similar to that of mountaineers. These findings are similar to those of other studies, which have found that risk-taking sports people score high on the measure of sensation seeking (very similar to novelty- seeking). What this suggests is that biology and genetics do, indeed, play at least a moderate role in determining who will take up adventure sports. We know that harm- avoidance, novelty-seeking and sensation-seeking are genetically inherited and determined by the levels of a number of brain neurotransmitters, called monoamines. These monoamines (dopamine and serotonin) are chemicals that pass information between lower and higher brain regions. High novelty-seeking and sensation-seeking are both associated with low levels of dopamine and involvement in risk-taking activities may help to boost the levels of this brain neurotransmitter. It has also been established that individuals who score high on these measures are at significant risk of developing drug and alcohol addictions and are more frequently involved in reckless behaviours and criminal activities. High harm-avoidance, which confers a propensity to become anxious or scared in the face of risk or uncertainty, is related to levels of serotonin in the brain. Risk-taking sports people have low levels of harm-avoidance and this may explain why they are able to tolerate risk without becoming overwhelmed by fear and anxiety. In fact, the low levels of harm-avoidance may contribute to a tendency to underestimate danger and therefore may partially account for the high rates of accidents. The study of risk-taking sportspeople provides interesting and compelling results. Not surprisingly sports, such as mountaineering and base jumping, are associated with a significant risk of injury and death. People who choose to take up these sports appear to have a unique biological make-up and these differences in brain chemistry help to explain why they choose to put themselves in peril. Although the risks are not insignificant, risk-taking instincts may well be better off channelled into adventure sports, where experience and training can minimise danger, than to drug addictions and anti-social or criminal behaviours. Erik Monasterio is a Bolivian/New Zealand medical doctor and mountaineer, specialising in forensic psychiatry. FlyCookie: That author's blurb is one of the most surreal sentences I've read in, erm, quite a while.

|

|

|

|

Post by FlyNavy on Jan 14, 2008 18:07:58 GMT 12

O 'One who flew over the Cookie Nest': Do you refer to the surreal last sentence as a blurb? Sounds to me like Erik is an 'Alpacan Sheep medico trick cyclist' with too many rocks in his head? ;D But then again I'm HARM avoiding by saying that.

|

|

|

|

Post by flycookie on Jan 17, 2008 13:30:41 GMT 12

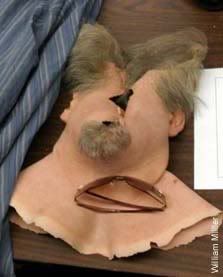

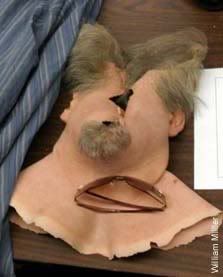

FlyCookie; Before reading the story, click on this video link to see what happened. All this from today's New York Post (was front page story in early editions). If nothing else, this fella knows how to generate masses of publicity. The Post is the local district office of the Murdoch Empire, and its editor in chief is a native of Dubbo, NSW. Strange but true. VIDEO LINK HERE: www.nypost.com/video/?vxSiteId=0db7b365-a288-4708-857b-8bdb545cbd0f&vxChannel=NY%20Post&vxClipId=1458_224594&vxBitrate=300www.nypost.com/seven/01162008/news/regionalnews/let_me_go_or_ill_die_341645.htm 'LET ME GO OR I'LL DIE' By DAREH GREGORIAN January 16, 2008 -- "I will fall and I will die if you do not let me go - I will fall and I will die." That's what daredevil Jeb Corliss told security guards at the Empire State Building as they grabbed him and stopped him from leaping off the landmark's 86th-floor observation deck, new video of the April 2006 incident shows. Corliss and his lawyer, Mark Jay Heller, released the dramatic footage after they filed a $30 million suit against the Empire State Building and the guards who Corliss claims nearly caused him a grisly death. The building last year filed a $12 million suit against Corliss, charging that his attempted stunt endangered "the ESB's customers, tenants, visitors and employees, as well as the public at large." Corliss - an experienced BASE (building, antenna, span, earth) jumper - said he knew exactly what he was doing, and was not endangering anyone. "No one was in any danger of being injured except me," said Corliss, 31. A spokeswoman for the skyscraper declined comment. Corliss had managed to sneak his gear into the building by wearing a "fat" suit and a disguise. He ditched the suit in the observatory bathroom, but was still wearing his phony handlebar moustache when he tried to make his leap, the video shows. The guards cuffed him to the fence - a move that could have been fatal to him had any of them come into contact with his parachute, Heller said. Had the chute opened while he was cuffed, it would have torn his torso from his limbs, Heller claims. Corliss said he begged the guards to listen to him, but they ignored his pleas. He credits cops with saving his life by cutting the chute off him. He was arrested and charged with reckless endangerment, but a judge tossed that charge. The Manhattan District Attorney's Office is appealing the ruling. The Empire State Building's suit charges that Corliss hurt its business because officials had to close the observation deck for a few hours . Corliss said what the guards did caused him to develop "adrenal-fatigue syndrome," similar "to battle-fatigue syndrome." EDITORIAL IDIOT JUMPER, IDIOT JUDGE January 16, 2008 -- Dumb judges beget dumb lawsuits. The dumb jurist du jour is state Supreme Court Justice Michael Ambrecht, who last January threw out reckless-endangerment charges against moron parachutist Jeb Corliss. Because no specific law prohibits parachuting from the Empire State Building - and because Corliss was a trained jumper - he did nothing illegal in trying the stunt in April 2006, Ambrecht ruled. Never mind that Corliss could've seriously injured someone on the ground (or worse) had his parachute failed. Or that he could have landed in the middle of traffic. Or . . . the list could go on. It's called reckless endangerment - and it's a broad charge for a reason. As it was, Corliss did injure one security officer as he fought with guards who subdued him seconds before his jump. Not that that mattered to Ambrecht, whose ruling opened the door for countless potential copycats. And now, it appears, a lawsuit. Corliss filed a $30 million claim against the Empire State Building yesterday, arguing that the guards who prevented his jump not only caused him "severe emotional distress" but endangered his life as well. And why not - if, as Ambrecht ruled, Corliss was completely within his rights to try the stunt? Fortunately, common sense may yet win out. A four-judge appeals panel last week heard arguments from the Manhattan DA's office urging it to reinstate the charges against Corliss. Here's hoping it does. Corliss' recklessness should earn him 30 days in Rikers, not a litigation jackpot. And, in justice, Judge Ambrecht should be sitting right beside him. Sad to say, stupidity isn't a crime.

|

|

|

|

Post by FlyNavy on Jan 17, 2008 14:59:25 GMT 12

Actually this is all getting really sad. "Let me go or I will die"? Stupidity is a crime but often people die from it without the court case to apportion blame.

|

|

|

|

Post by flycookie on Mar 6, 2008 15:35:27 GMT 12

From today's New York Post. www.nypost.com/seven/03052008/news/regionalnews/oh__chute__rap_is_back_100525.htmOH, CHUTE! RAP IS BACK

EMPIRE STATE DAREDEVIL FACES NEW COUNTBy LAURA ITALIANO  LANDING IN TROUBLE: Jeb Corliss  Wannaba birdman's fat suit March 5, 2008 -- That'll take the wind out of his parachute. High-flying daredevil Jeb Corliss once again faces criminal charges for his flamboyant but foiled April 2006 attempt to jump off the Empire State Building. The California stunt diver's antics could have caused death and destruction in myriad ways, a state appeals court wrote in a decision published yesterday that reinstates charges a lower court had dismissed in January. Corliss, through his lawyer, is vowing an appeal. "Climbing over the security fence to a position where, according to one security guard, he appeared ready to jump off the building, in itself put many people at risk," the panel wrote. "Even an accidental misstep, or a hand or object reaching through the security fence and accidentally pushing, rather than grabbing him, could have sent the defendant into the air, where a faulty parachute would result in a likelihood of death." A piece of the daredevil's equipment, the judges said, could have plummeted to Earth, becoming a "lethal projectile." Guards, alerted by a tipster, had been on the lookout for Corliss that day. He managed to sneak himself, his parachute and a camera-equipped helmet up to the observation deck - hidden in a fat suit and fake mustache. But security did see him as he emerged, transformed into a stunt-diving-guy, from the men's room. They grabbed him through the security fence after he'd scaled it to the other side, but before he could jump. The guards cuffed him to the fence and cut off his parachute to keep him from jumping, and he was quickly arrested. Corliss had enjoyed a brief reprieve from prosecution a year ago, after a Manhattan Supreme Court judge ruled the stunt wasn't technically reckless enough to be criminal. Corliss, who has 3,000 successful jumps to his credit, had planned his jump for 10 years to ensure the safety of the crowds below, the lower court judge, Michael Ambrecht, had ruled. But that reprieve was overturned yesterday, giving Manhattan prosecutors the go-ahead to once again pursue at least misdemeanor charges that Corliss recklessly endangered the rush-hour crowds below. A misdemeanor conviction could put him in jail for a year. Prosecutors also have the option of again pursuing felony charges that carry a whopping seven-year maximum sentence - but they'd first have to convince a grand jury that Corliss showed a "depraved indifference" to the risk of killing bystanders. Corliss was merely "executing his constitutional right to freedom of expression by flying through the air," said his lawyer, Mark Jay Heller. |

|

|

|

Post by FlyNavy on Mar 6, 2008 16:26:43 GMT 12

"...had planned his jump for 10 years to ensure the safety of the crowds below..." QUE? This statement smacks of the suspect recent 'Airshow Planner statements' - now postponed for 'safety reasons'.

|

|

Perhaps English (and sanity) are a second language.

Perhaps English (and sanity) are a second language.