Post by nuuumannn on Jul 4, 2012 15:09:52 GMT 12

Gidday Folks,

This is a thread I posted in another forum I visit and I'm not entirely convinced that it fits here, nevertheless, here it is. I've been a bit nervous about posting it since it is very close to home for many of you, myself included. Recently my father passed away and I thought it might be the last time I went to the area, so I took these pictures, being into history 'n all, but I was back last week and thus I decided to post them in deference to historical interest. Please let me know what you think.

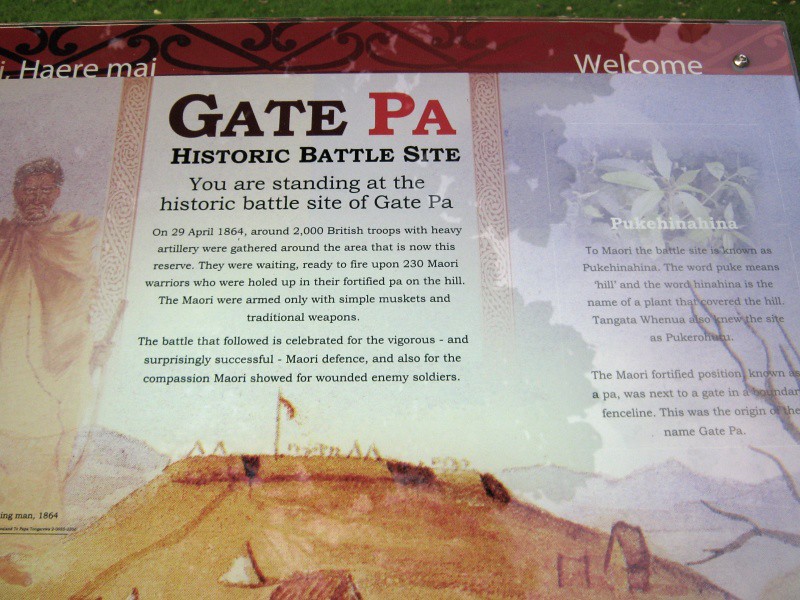

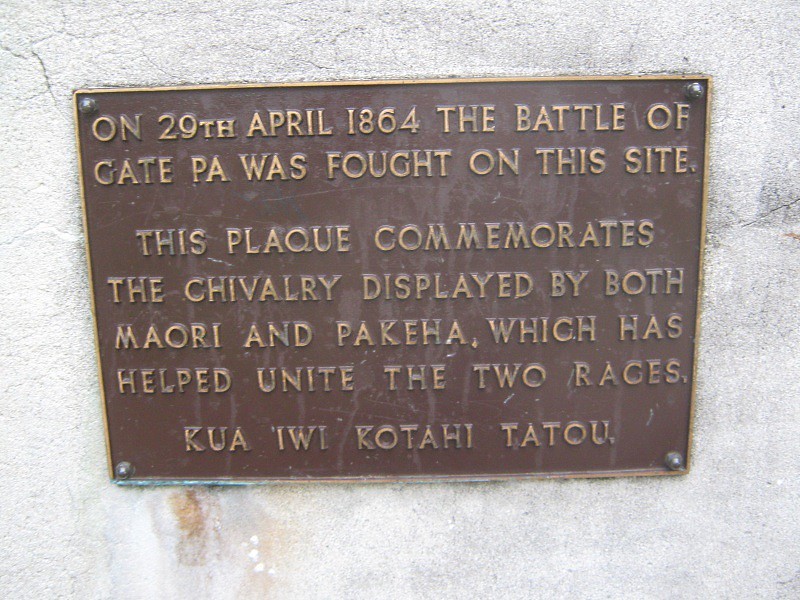

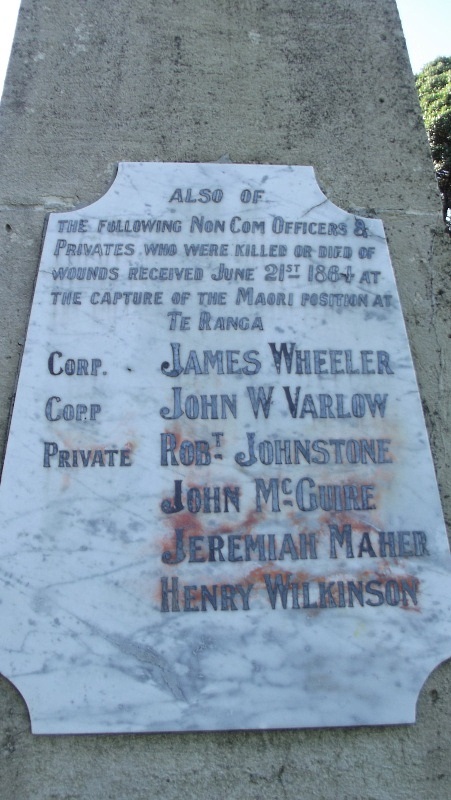

Without going into the politics of race relations, here is a bit of history about the Battle of Gate Pa, which took place on the 28th and 29th of April 1864. At the time it was considered one of the most humiliating defeats the British army had suffered.

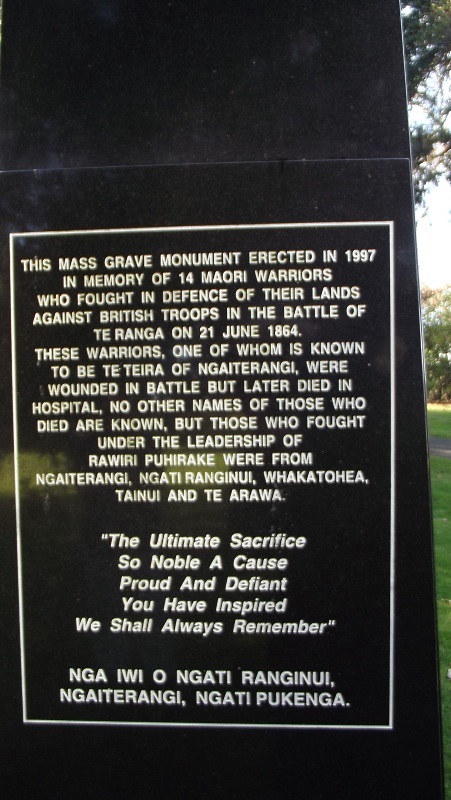

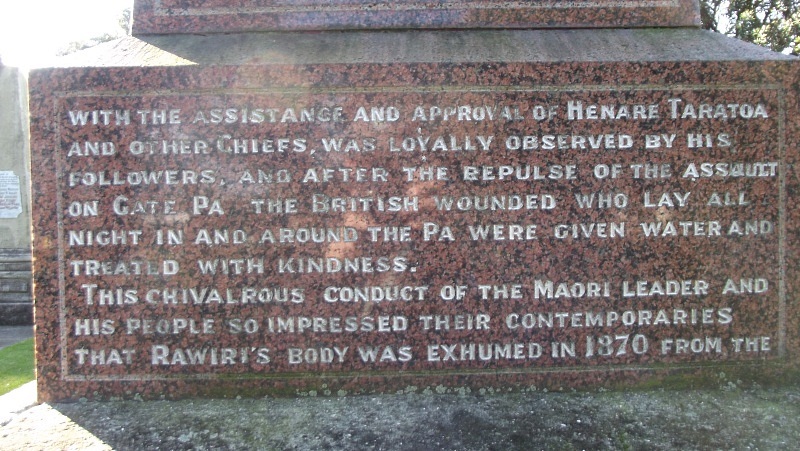

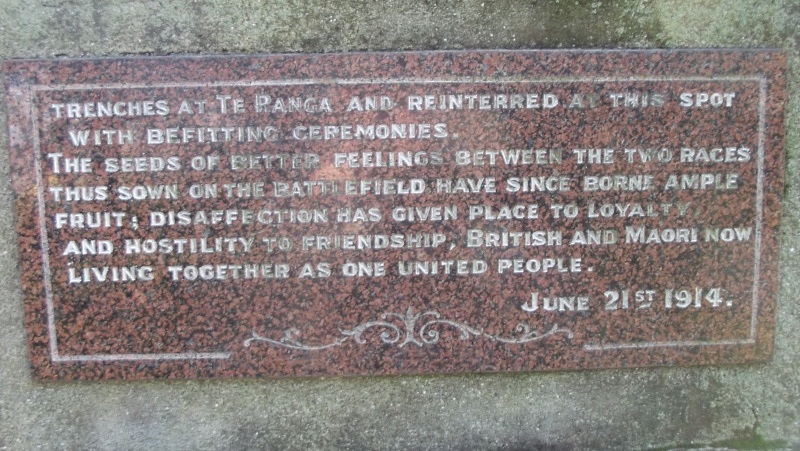

At that time, on the Tauranga peninsula the local tribes and the small number of settlers shared an uneasy peace, with territory divided by a simple fence about three miles from the colonial settlement, located at the very tip of the Tauranga peninsula. The incumbent tribe was Ngai Te Rangi, members of which became startled by a sudden influx of British soldiers to the area in January 1864. With war raging in the nearby Waikato, Ngai Te Rangi's chief, Rawiri Puhirake had sent men in support of the insurrection. With the arrival of British ships carrying soldiers, these were quickly recalled.

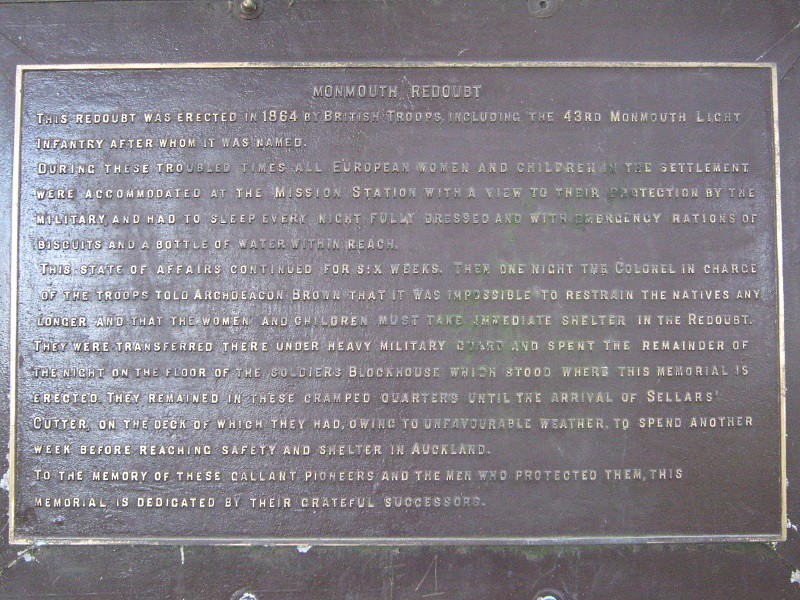

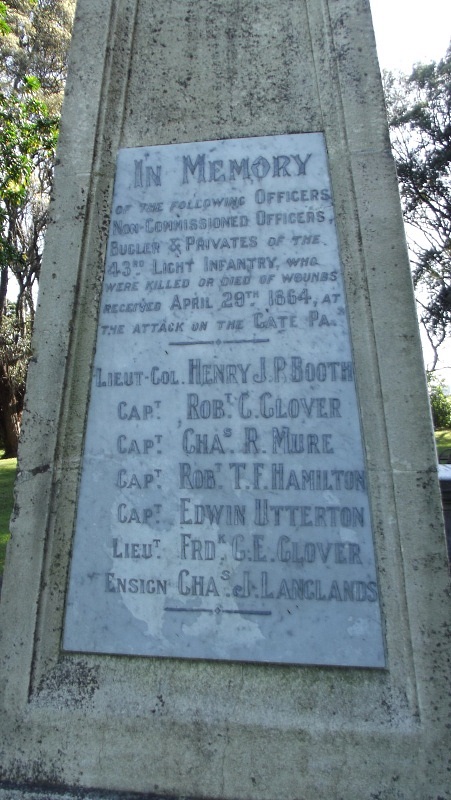

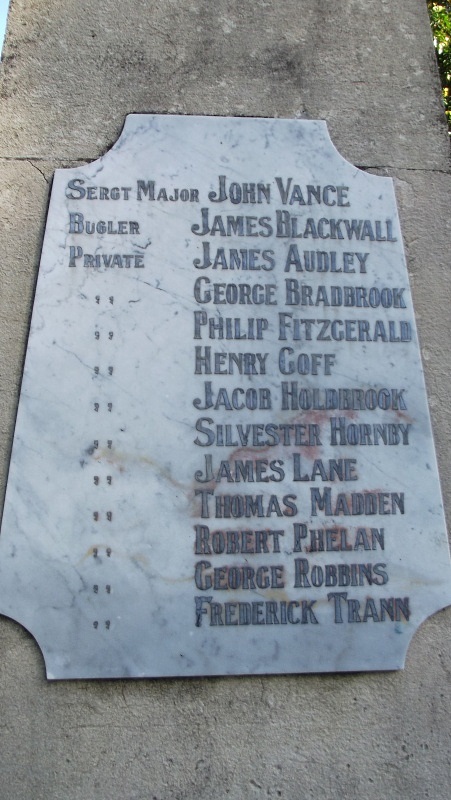

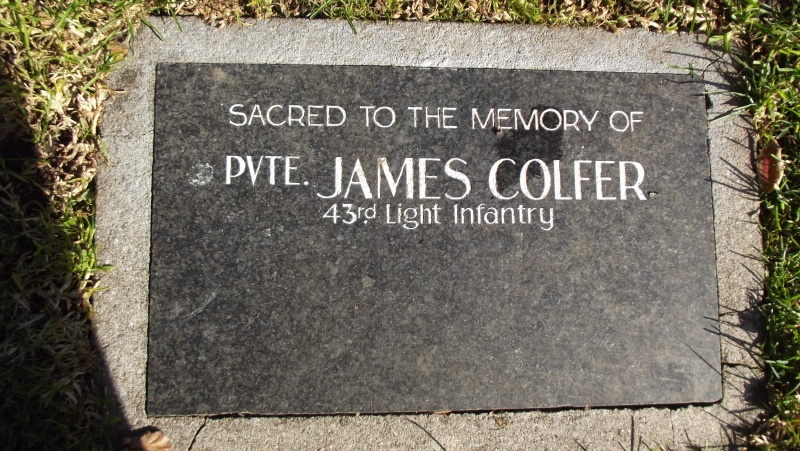

On 22 January some 600 men, primarily of the elite 43rd Monmouth and 68th Durham Light Infantry Regiments disembarked from the ships Miranda and Corio. Two earthwork redoubts were constructed and named after the two regiments to defend the military emcampment. On instruction from Governor George Grey in Auckland, the soldiers were sent to Tauranga to prevent personnel and supplies from reaching the Waikato from tribes further along the coast, which used the bay as a landing point.

Cameron's things

Cameron's things

Personal items belonging to Gen Duncan Alexander Cameron, who led the attack on the Pukehinahina pa, on display in the National Army Museum, Waiouru.

Once Puhirake's men had returned from the Waikato, a pa was built some miles inland from the British camp. Traditionally, the pa was a fortified defensive position resembling similar such barricades around the world, including the British redoubts that sprang up several miles to the west of the one at Te Waoku. By this time however, the Maori pa had evolved into a weapon of considerable advantage to themselves; it had become an offensive position; without precedent in military history (more of which later).

Continuing with tradition, the construction of a modern pa was effectively a declaration of war, but Puhirake's taunts went unanswered by the emcampment's commander, Lieutenant Colonel H.H. Greer, even after, with considerable courtesy and not a little humour, Puhirake offered to build a road to the pa to ease his enemy's journey into battle.

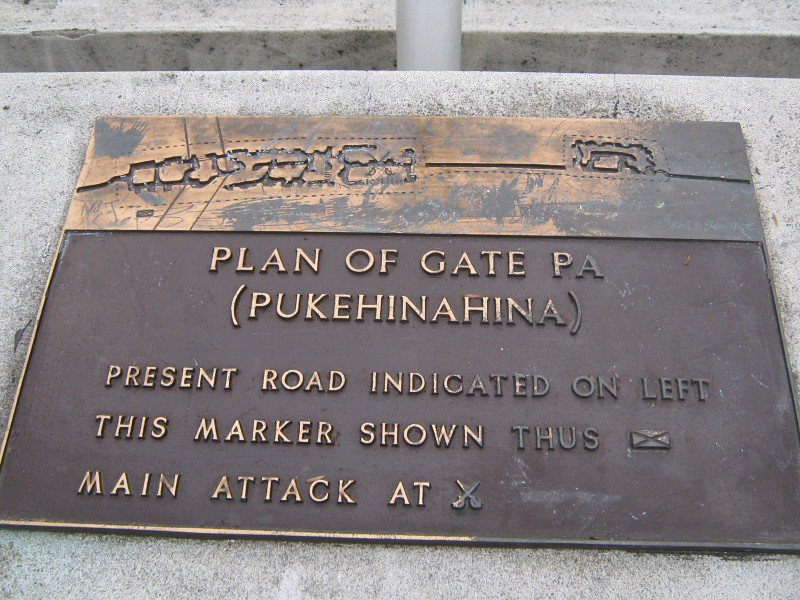

In early April however, further provocation by Puhirake came in the form of the construction of a second pa on a prominent rise, this time only three miles away from and in full view of the government settlement. This new fortification sat at the border between Maori and European territory next to a gateway between the two. To the settlers, it became known as the Gate Pa. At Pukehinahina the new pa was was of intricate design of surface trenches and underground tunnels; a rectangle measuring 90 by 18 metres, with a smaller section, just 26 by 18 m that was connected to the former by a trench 300 m long.

Puhirake's flag

Puhirake's flag

Puhirake's battle flag that flew from the flag pole mounted within the pa at Pukehinahina on display at the Auckland War Memorial Museum. At bottom left is a whale bone tewhatewha two handed club, recovered from the Gate Pa site in 1875. To the flag's left is a contemporary drawing of Rawiri Puhirake.

With this advanced position, the threat could no longer be ignored. When Governor Grey heard the news, the military commander General Duncan Alexander Cameron was sent to Tauranga to make plans for war. By 26 April, Cameron and some 1,700 men were garrisoned at Tauranga, along with a formidable array of artillery pieces, comprising two 24-pounder howitzers, two eight-inch mortars and six naval Coehorn mortars, as well as five of the much feared Armstrong guns; two six-pounders, two 40-pounders and a massive 110-pounder. Against this powerful force, Puhirake had 235 warriors, primarily from Ngai Te Rangi, but also from Hauraki and Waikato tribes.

By early afternoon on the 28th, the British force was ranged on the rise to the west of Pukehinahina Pa. As a precaution Cameron had sent the 68th Durham to the north of the pa along the foreshore to block the escape of any of the natives. As was customary, the battle began with the artillery pieces launching a fearsome barrage, the likes of which had never been seen on New Zealand soil before. For over an hour the guns pounded away at the pa before retiring and beginning early the next day.

Armstrong breech loading gun

Armstrong breech loading gun

A 6 pounder Armstrong breech loading field gun on its carriage, with mannequins in period field wear. Two of these guns were used at Gate Pa and proved efficient. This one is on display at the National Army Museum, Waiouru.

From dawn on the 29th the big guns blasted away again until shortly before 4pm, at which point a massive hole could be seen in the ramparts. There was little movement from within the pa, but figures could be made out moving about in the trenches. Next it was the infantry's turn and a rifle barrage signified its advance. Led by the 43rd Monmouth, some 300 soldiers marched toward the smoking pa and entered the breach, there was little resistance to their advance. Once inside the pa however, they were doomed. Ten minutes later, through the swirling smoke, stricken British soldiers could be seen fleeing the pa, screaming and bloody from flesh wounds.

Some 111 British soldiers had been killed in the violent scrap that ensued within the ruined pa, which left only 25 of Puhirake's men dead. Gate Pa is regarded as the most significant, if not decisive battle of the New Zealand wars. To the British back home and among British in New Zealand it was a crushing defeat. Although melodramatic of tone, a passage from an article published in The Times on 14 July 1864 titled “Samuel Mitchell and the Victoria Cross” reflects the mood following the battle;

“The night of the 29th of April was, in the British camp at Tauranga, a night of deep humiliation and mutual reproach. The men were disgraced in their own eyes, and what would the people of England say? There is not a more gallant regiment in the service than the 43rd... But now where were all the laurels they had won in the Peninsula and India? Soiled and trampled in the dust and by whom? Not by forces equal to them in arms and discipline; not by foemen worthy of their steel; but by a horde of half naked, half armed savages, whom they had been taught to despise.”

Part Two to follow.

This is a thread I posted in another forum I visit and I'm not entirely convinced that it fits here, nevertheless, here it is. I've been a bit nervous about posting it since it is very close to home for many of you, myself included. Recently my father passed away and I thought it might be the last time I went to the area, so I took these pictures, being into history 'n all, but I was back last week and thus I decided to post them in deference to historical interest. Please let me know what you think.

Without going into the politics of race relations, here is a bit of history about the Battle of Gate Pa, which took place on the 28th and 29th of April 1864. At the time it was considered one of the most humiliating defeats the British army had suffered.

At that time, on the Tauranga peninsula the local tribes and the small number of settlers shared an uneasy peace, with territory divided by a simple fence about three miles from the colonial settlement, located at the very tip of the Tauranga peninsula. The incumbent tribe was Ngai Te Rangi, members of which became startled by a sudden influx of British soldiers to the area in January 1864. With war raging in the nearby Waikato, Ngai Te Rangi's chief, Rawiri Puhirake had sent men in support of the insurrection. With the arrival of British ships carrying soldiers, these were quickly recalled.

On 22 January some 600 men, primarily of the elite 43rd Monmouth and 68th Durham Light Infantry Regiments disembarked from the ships Miranda and Corio. Two earthwork redoubts were constructed and named after the two regiments to defend the military emcampment. On instruction from Governor George Grey in Auckland, the soldiers were sent to Tauranga to prevent personnel and supplies from reaching the Waikato from tribes further along the coast, which used the bay as a landing point.

Cameron's things

Cameron's thingsPersonal items belonging to Gen Duncan Alexander Cameron, who led the attack on the Pukehinahina pa, on display in the National Army Museum, Waiouru.

Once Puhirake's men had returned from the Waikato, a pa was built some miles inland from the British camp. Traditionally, the pa was a fortified defensive position resembling similar such barricades around the world, including the British redoubts that sprang up several miles to the west of the one at Te Waoku. By this time however, the Maori pa had evolved into a weapon of considerable advantage to themselves; it had become an offensive position; without precedent in military history (more of which later).

Continuing with tradition, the construction of a modern pa was effectively a declaration of war, but Puhirake's taunts went unanswered by the emcampment's commander, Lieutenant Colonel H.H. Greer, even after, with considerable courtesy and not a little humour, Puhirake offered to build a road to the pa to ease his enemy's journey into battle.

In early April however, further provocation by Puhirake came in the form of the construction of a second pa on a prominent rise, this time only three miles away from and in full view of the government settlement. This new fortification sat at the border between Maori and European territory next to a gateway between the two. To the settlers, it became known as the Gate Pa. At Pukehinahina the new pa was was of intricate design of surface trenches and underground tunnels; a rectangle measuring 90 by 18 metres, with a smaller section, just 26 by 18 m that was connected to the former by a trench 300 m long.

Puhirake's flag

Puhirake's flag Puhirake's battle flag that flew from the flag pole mounted within the pa at Pukehinahina on display at the Auckland War Memorial Museum. At bottom left is a whale bone tewhatewha two handed club, recovered from the Gate Pa site in 1875. To the flag's left is a contemporary drawing of Rawiri Puhirake.

With this advanced position, the threat could no longer be ignored. When Governor Grey heard the news, the military commander General Duncan Alexander Cameron was sent to Tauranga to make plans for war. By 26 April, Cameron and some 1,700 men were garrisoned at Tauranga, along with a formidable array of artillery pieces, comprising two 24-pounder howitzers, two eight-inch mortars and six naval Coehorn mortars, as well as five of the much feared Armstrong guns; two six-pounders, two 40-pounders and a massive 110-pounder. Against this powerful force, Puhirake had 235 warriors, primarily from Ngai Te Rangi, but also from Hauraki and Waikato tribes.

By early afternoon on the 28th, the British force was ranged on the rise to the west of Pukehinahina Pa. As a precaution Cameron had sent the 68th Durham to the north of the pa along the foreshore to block the escape of any of the natives. As was customary, the battle began with the artillery pieces launching a fearsome barrage, the likes of which had never been seen on New Zealand soil before. For over an hour the guns pounded away at the pa before retiring and beginning early the next day.

Armstrong breech loading gun

Armstrong breech loading gun A 6 pounder Armstrong breech loading field gun on its carriage, with mannequins in period field wear. Two of these guns were used at Gate Pa and proved efficient. This one is on display at the National Army Museum, Waiouru.

From dawn on the 29th the big guns blasted away again until shortly before 4pm, at which point a massive hole could be seen in the ramparts. There was little movement from within the pa, but figures could be made out moving about in the trenches. Next it was the infantry's turn and a rifle barrage signified its advance. Led by the 43rd Monmouth, some 300 soldiers marched toward the smoking pa and entered the breach, there was little resistance to their advance. Once inside the pa however, they were doomed. Ten minutes later, through the swirling smoke, stricken British soldiers could be seen fleeing the pa, screaming and bloody from flesh wounds.

Some 111 British soldiers had been killed in the violent scrap that ensued within the ruined pa, which left only 25 of Puhirake's men dead. Gate Pa is regarded as the most significant, if not decisive battle of the New Zealand wars. To the British back home and among British in New Zealand it was a crushing defeat. Although melodramatic of tone, a passage from an article published in The Times on 14 July 1864 titled “Samuel Mitchell and the Victoria Cross” reflects the mood following the battle;

“The night of the 29th of April was, in the British camp at Tauranga, a night of deep humiliation and mutual reproach. The men were disgraced in their own eyes, and what would the people of England say? There is not a more gallant regiment in the service than the 43rd... But now where were all the laurels they had won in the Peninsula and India? Soiled and trampled in the dust and by whom? Not by forces equal to them in arms and discipline; not by foemen worthy of their steel; but by a horde of half naked, half armed savages, whom they had been taught to despise.”

Part Two to follow.