Incredible! Balloon Flight From Besieged Paris 100 Years Ago

Jun 15, 2022 19:43:48 GMT 12

oj likes this

Post by Dave Homewood on Jun 15, 2022 19:43:48 GMT 12

This is fascinating. I know practically nothing about the Franco-Prussian war on 1870. I never expected there to be aviation involved! This article is from The Press dated 5 September 1970, so the actual siege was 152 years ago!

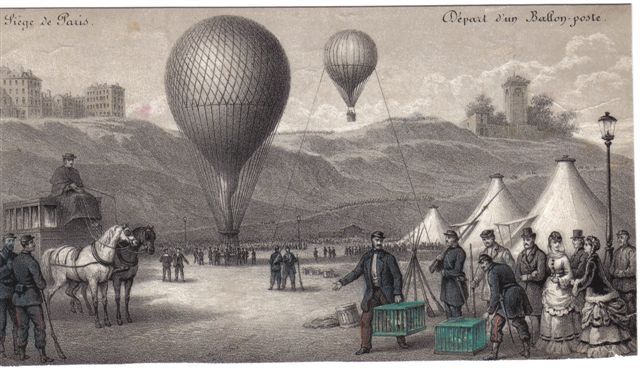

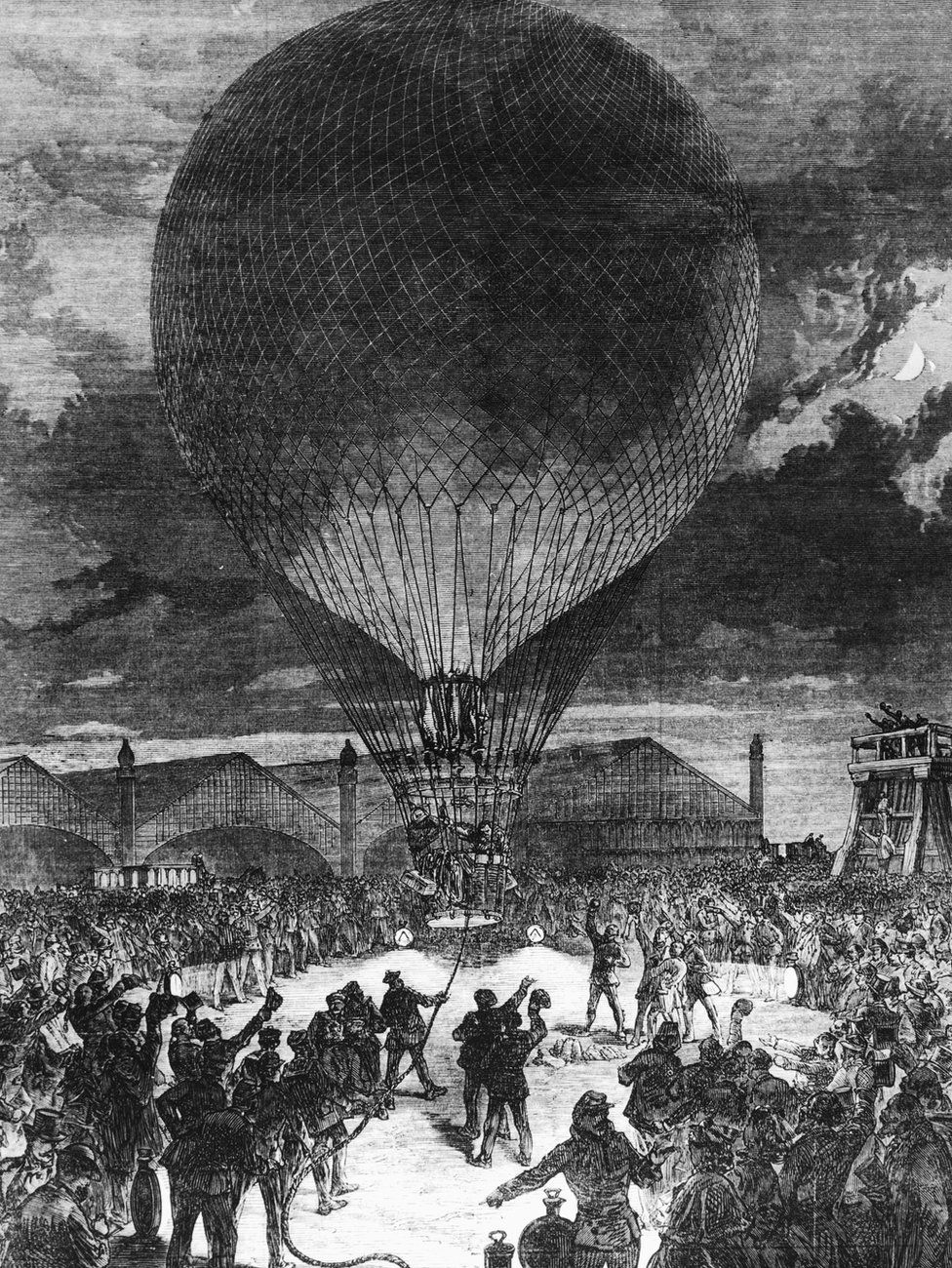

Balloon Flight From Besieged Paris 100 Years Ago

(By BASIL CLARKE)

Flying is today very much a part of ordinary life and we have already celebrated the fiftieth anniversaries of the Royal Air Force, of the first Atlantic flight and of at least one international airline. What is less well known is that we are celebrating a very important aeronautical centenary.

When the Prussian army surrounded Paris in 1870 the siege was complete and the government was completely cut off from unoccupied France. Many brave men tried to penetrate the cordon but they were always caught and the rest of France was in a state of chaos.

In Paris there were several balloons—in varying states of goodness—and some of the great balloonists of the day. Among theme were Gaston Tissandier, Eugene Godard, Jules Durouf, Mangin, de Fonviile and Nadar. Hydrogen could be manufactured in the city.

So on September 23, 1870, Jules Durouf ascended with a load of dispatches and, three hours later, landed at Evreux, some 60 miles away. The Germans were not happy and when Tissandier, who was next to go, sailed over their heads he was greeted with salvoes of musketry fire. Ack-ack was even less efficient then than in the 1939-1945 war and Tissandier got safely out.

Within a week from Durouf’s flight four balloons got through, the last two being flown respectively by Godard’s son and Mangin.

Lack Of Pilots

So far so good but a difficult situation now arose. The balloons remaining were in a very poor state and there were only three real experts able to fly them. It was decided that these men would supervise the construction of new balloons and the training of aircrew. Where these aircrew were to come from was quite another matter. The average man was even less airminded then than he is now and volunteers to take a course of training were just non-existent.

Then the government had a brilliant idea. Performing at at Paris Hippodrome had been a party of acrobats and they, in common with everyone else, were locked up in the city. Accustomed to working high up they seemed to present ideal material and were promptly conscripted. It will be appreciated that the only training they could be given would be of a theoretical nature with, perhaps, an ascent to around 80 feet in a tethered balloon. It is one thing to train a pilot on the ground but quite another to send him off on his first solo, with a load of passengers and mail, in a new balloon which has never flown free before.

Add to that the fact that within a few minutes the flight is over enemy territory and that the enemy has taken an intense dislike to balloonists and is ready and willing to signal his dislike in an extremely hostile fashion. Who shall blame the acrobats for taking a dim view? What was not realised was that these men had a way out not open to most people.

Quick Descent

Almost immediately after leaving the ground they slid expertly down the trail rope —valving some gas if necessary—and returned to terra firma. The balloon, being considerably lightened, shot skywards with passenger(s) and mail and travelled according to the vagaries of the wind to an unresolved destination.

Acrobats being a dead loss some other expedient had to be adopted and then someone in the government had a stroke of genius. Bottled up in the city for some reason which has never been explained there were large numbers of French navy sailors. Disciplined men, they had plenty of experience of the effects of the wind and they were paid to get killed in the line of duty anyway. The experiment was a success and, flown by the matelots, the airlift was on.

Naturally, there were incidents. The Daguerre was shot down on November 12 and some of the others had to land in German-occupied areas. Night flying was then introduced and this confounded the Prussians but introduced other problems for the aeronauts.

We used to complain bitterly enough about weather forecasts in the last war but they were the products of genius compared to what was available in Paris 100 years ago. Consequently, when the balloon left the ground in darkness no-one had much if any idea of where it would fetch up.

Economic Problem

Some remarkable flights were made—or happened. One balloon came down in the snow in Norway after being fired on by a British naval ship in the North Sea. Apparently the Royal Navy concept of firing first and asking questions later was in existence a century ago. The crew was exhausted but they saved their dispatches.

Another flight terminated in Holland but most of them came down in friendly, if unknown, country. There was another problem, an economic one, This was strictly a one-way-only operation. Once out of Paris the balloon had no further military use.

Tissandier, probably the greatest balloonist, made attempt after attempt to fly back but the winds never allowed him to succeed. And it was all very well to get messages out but less useful if no information could be sent back.

Dogs were flown out with the idea that they would be able to get back through the enemy lines carrying messages but not one of them ever returned. Perhaps they thought that going back to very strict rationing offered little attraction.

Pigeons, of which a number were carried over the lines, did manage to get back on occasion, thus establishing the first two-way air mail service.

The last balloon, the sixty-sixth flight, carried news of the surrender of Paris on January 28, 1871.

In retrospect this was a most remarkable operation. Joint civil and military, it embodied features which would horrify an air transport operator today.

Untried Balloons

Every flight after the first four by the expert aeronauts took place under conditions which most people would not even contemplate. The balloon was new and had never flown free before. The pilot had never flown even as a passenger. The flight commenced in darkness and the crew knew as little about the destination as did the passengers. The first period of the flight was over enemy territory and, to cap it all, the craft was expendable as it could never get back.

A modem comparison except in cash values—would be a VC 10 airliner leaving Hong Kong under the command of a captain who had never been up before, flying over Red Chinese territory for a time and hoping that there was enough fuel to reach some friendly place which happened to have a suitable landing strip.

However, the Paris air lift worked. In 66 flights 57 of the balloons arrived safely somewhere, 155 passengers were flown out and the mail carried weighed nine tons. All in all, an achievement that certainly deserves a centenary celebration.

Balloon Flight From Besieged Paris 100 Years Ago

(By BASIL CLARKE)

Flying is today very much a part of ordinary life and we have already celebrated the fiftieth anniversaries of the Royal Air Force, of the first Atlantic flight and of at least one international airline. What is less well known is that we are celebrating a very important aeronautical centenary.

When the Prussian army surrounded Paris in 1870 the siege was complete and the government was completely cut off from unoccupied France. Many brave men tried to penetrate the cordon but they were always caught and the rest of France was in a state of chaos.

In Paris there were several balloons—in varying states of goodness—and some of the great balloonists of the day. Among theme were Gaston Tissandier, Eugene Godard, Jules Durouf, Mangin, de Fonviile and Nadar. Hydrogen could be manufactured in the city.

So on September 23, 1870, Jules Durouf ascended with a load of dispatches and, three hours later, landed at Evreux, some 60 miles away. The Germans were not happy and when Tissandier, who was next to go, sailed over their heads he was greeted with salvoes of musketry fire. Ack-ack was even less efficient then than in the 1939-1945 war and Tissandier got safely out.

Within a week from Durouf’s flight four balloons got through, the last two being flown respectively by Godard’s son and Mangin.

Lack Of Pilots

So far so good but a difficult situation now arose. The balloons remaining were in a very poor state and there were only three real experts able to fly them. It was decided that these men would supervise the construction of new balloons and the training of aircrew. Where these aircrew were to come from was quite another matter. The average man was even less airminded then than he is now and volunteers to take a course of training were just non-existent.

Then the government had a brilliant idea. Performing at at Paris Hippodrome had been a party of acrobats and they, in common with everyone else, were locked up in the city. Accustomed to working high up they seemed to present ideal material and were promptly conscripted. It will be appreciated that the only training they could be given would be of a theoretical nature with, perhaps, an ascent to around 80 feet in a tethered balloon. It is one thing to train a pilot on the ground but quite another to send him off on his first solo, with a load of passengers and mail, in a new balloon which has never flown free before.

Add to that the fact that within a few minutes the flight is over enemy territory and that the enemy has taken an intense dislike to balloonists and is ready and willing to signal his dislike in an extremely hostile fashion. Who shall blame the acrobats for taking a dim view? What was not realised was that these men had a way out not open to most people.

Quick Descent

Almost immediately after leaving the ground they slid expertly down the trail rope —valving some gas if necessary—and returned to terra firma. The balloon, being considerably lightened, shot skywards with passenger(s) and mail and travelled according to the vagaries of the wind to an unresolved destination.

Acrobats being a dead loss some other expedient had to be adopted and then someone in the government had a stroke of genius. Bottled up in the city for some reason which has never been explained there were large numbers of French navy sailors. Disciplined men, they had plenty of experience of the effects of the wind and they were paid to get killed in the line of duty anyway. The experiment was a success and, flown by the matelots, the airlift was on.

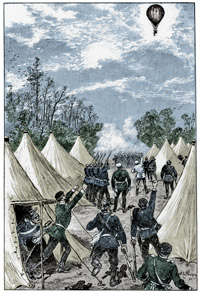

Naturally, there were incidents. The Daguerre was shot down on November 12 and some of the others had to land in German-occupied areas. Night flying was then introduced and this confounded the Prussians but introduced other problems for the aeronauts.

We used to complain bitterly enough about weather forecasts in the last war but they were the products of genius compared to what was available in Paris 100 years ago. Consequently, when the balloon left the ground in darkness no-one had much if any idea of where it would fetch up.

Economic Problem

Some remarkable flights were made—or happened. One balloon came down in the snow in Norway after being fired on by a British naval ship in the North Sea. Apparently the Royal Navy concept of firing first and asking questions later was in existence a century ago. The crew was exhausted but they saved their dispatches.

Another flight terminated in Holland but most of them came down in friendly, if unknown, country. There was another problem, an economic one, This was strictly a one-way-only operation. Once out of Paris the balloon had no further military use.

Tissandier, probably the greatest balloonist, made attempt after attempt to fly back but the winds never allowed him to succeed. And it was all very well to get messages out but less useful if no information could be sent back.

Dogs were flown out with the idea that they would be able to get back through the enemy lines carrying messages but not one of them ever returned. Perhaps they thought that going back to very strict rationing offered little attraction.

Pigeons, of which a number were carried over the lines, did manage to get back on occasion, thus establishing the first two-way air mail service.

The last balloon, the sixty-sixth flight, carried news of the surrender of Paris on January 28, 1871.

In retrospect this was a most remarkable operation. Joint civil and military, it embodied features which would horrify an air transport operator today.

Untried Balloons

Every flight after the first four by the expert aeronauts took place under conditions which most people would not even contemplate. The balloon was new and had never flown free before. The pilot had never flown even as a passenger. The flight commenced in darkness and the crew knew as little about the destination as did the passengers. The first period of the flight was over enemy territory and, to cap it all, the craft was expendable as it could never get back.

A modem comparison except in cash values—would be a VC 10 airliner leaving Hong Kong under the command of a captain who had never been up before, flying over Red Chinese territory for a time and hoping that there was enough fuel to reach some friendly place which happened to have a suitable landing strip.

However, the Paris air lift worked. In 66 flights 57 of the balloons arrived safely somewhere, 155 passengers were flown out and the mail carried weighed nine tons. All in all, an achievement that certainly deserves a centenary celebration.